Two thousand years ago, Euclid discovered an enduring principle of aesthetic proportion known as the Golden Section. So perfect are the proportions of this design principle that the Renaissance mathematician Luca Pacioli renamed it De Divina Proportione, the ratio 1 to 1.6181 that dictates the perfect point at which to divide a line into two harmonious but unequal lengths. Over fifty years ago, Patek Philippe used the same principle of harmony and elegance to create the Golden Ellipse, a design that remains unique within the company portfolio.

It is no secret that the Patek Philippe Ellipse is Collectability’s favorite design. For us, it represents everything that is Patek — a modern, yet eternal canvas upon which all aspects of the artisan’s touch can flourish: the case maker, the chain maker, the goldsmith and dial maker, the jeweler, and of course, the watchmaker. As Thierry Stern said when celebrating the Ellipse’s 50th anniversary in 2018, “It’s one of those watches that shows you how to make a Patek Philippe. No gimmicks, just purity and beauty expressed through simple design.”

“The Golden Section is an aesthetic rule which has been known for many centuries. It defines harmony in proportions and was referred to as divina proportione, proportion continua, Golden Number, Golden Rule, and more recently, the Golden Section. But the Golden Section is older than its names, for it not only inspired man-made designs but is present also in nature, in the shapes of leaves, the spacing of buds along a branch on a tree, and the proportions of the human body. For the builder of Hellenic temples as for the friars who designed the great churches of the Middle Ages, the Golden Section remained a jealously guarded secret which master passed on to pupil in the strictest confidence” (Patek Philippe Advertisement, Circa 1968).

Born into the turbulent late 1960s, it was an instant icon in a changing world. The watch industry was about to experience its own revolution as quartz was just around the corner – and Patek Philippe was well aware of the potential impact ahead. Led by the then president, Henri Stern, Thierry Stern’s grandfather, the company needed a new watch design that was both immediately recognizable as a Patek and unisex in its appeal. The company also needed a watch that represented true luxury, something that would at a glance be distinguishable from any other watch. Advances in mass production meant that during the ‘60s, it was easier for cheaply produced watches to imitate the appearance of luxury timepieces. The launch of the first Ellipse in 1968 couldn’t have come at a better time. It was immediately embraced as forward looking and classic at the same time, while in a league of luxury not seen in the watch industry.

There is some debate as to who was responsible for the Golden Ellipse design. It is generally recognized that Jean-Daniel Rubeli, who was then Patek’s inhouse stylist was inspired by the Golden Section and thus created the iconic design. However, Jean-Pierre Frattini, who at the time was a young casemaker at Patek recalls that Georges Delessert, the then director of the electronics department was inspired to create the radical case design by the “pleasing shape of an American highway junction seen from the window of an airplane.”

Whether it inspired by a divine proportion or an American highway system, the Ellipse was a highly significant watch for Patek as it marked an important shift in manufacturing practice. Like most other watchmakers since the eighteenth century, Patek had relied on casemakers to propose designs from which it made a selection. The birth of the Ellipse was the complete opposite: Patek developed the design internally, then briefed the case maker Ateliers Réunis to produce it. This landmark shift in the balance of the relationship between Patek Philippe and its suppliers was a taste of things to come. Patek would later purchase Ateliers Réunis (its original manufacturing building is now home to the Patek Philippe Museum) and most of its other suppliers bringing as much production as possible in-house.

The dazzling, cobalt blue dial was another revolutionary step for the company: it was something no one had ever seen before: 18K blue gold. By the beginning of the 1960s, as part of its research commitment, Patek had begun to test the realms of alchemy by altering the very nature of gold itself. It experimented relentlessly with all types of gold until it really did create something new: blued gold. The initial inspiration for using blue gold on the dial is not clear, but Jean-Pierre Frattini believes that Jean-Daniel Rubeli knew a Genevois jeweler called Ludwig Müller who was famous at the time for making jewelry using blue gold. Maybe Müller helped to inspire the idea, but the actual creation of the ore to decorate a dial was another challenge altogether. The first attempt used the galvanic bath technique, basically electroplating an 18K gold dial ébauche. Unfortunately, the results were uneven with some dials even showing tints of brown. The final solution came with the help of the dial maker Singer that developed a system of vacuum plating in which cobalt and 24K gold are vaporized and then allowed to condense on the 18K gold dial. So revolutionary was the resulting material that the Swiss government’s precious metals bureau demanded detailed clarification on all steps of the process. It was not an easy dial to make, but it was worth the effort.

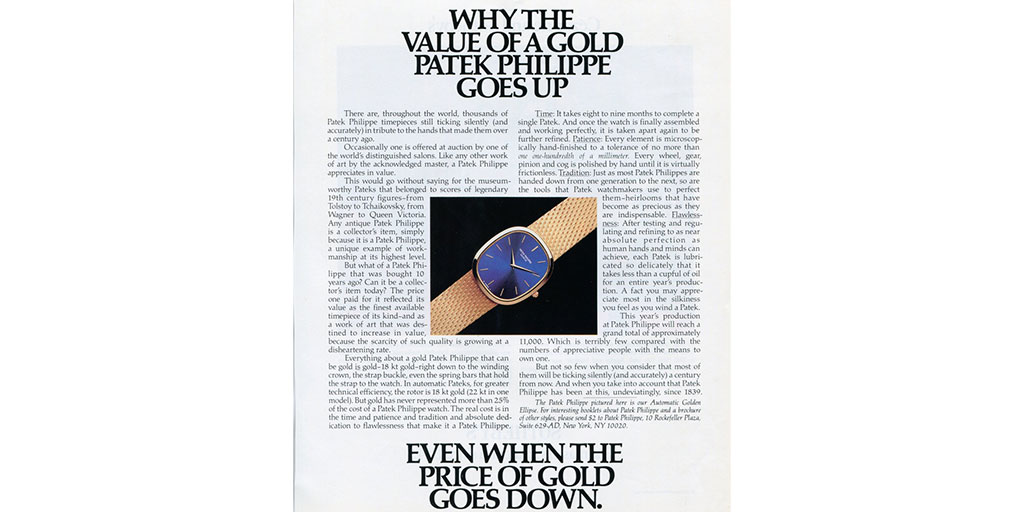

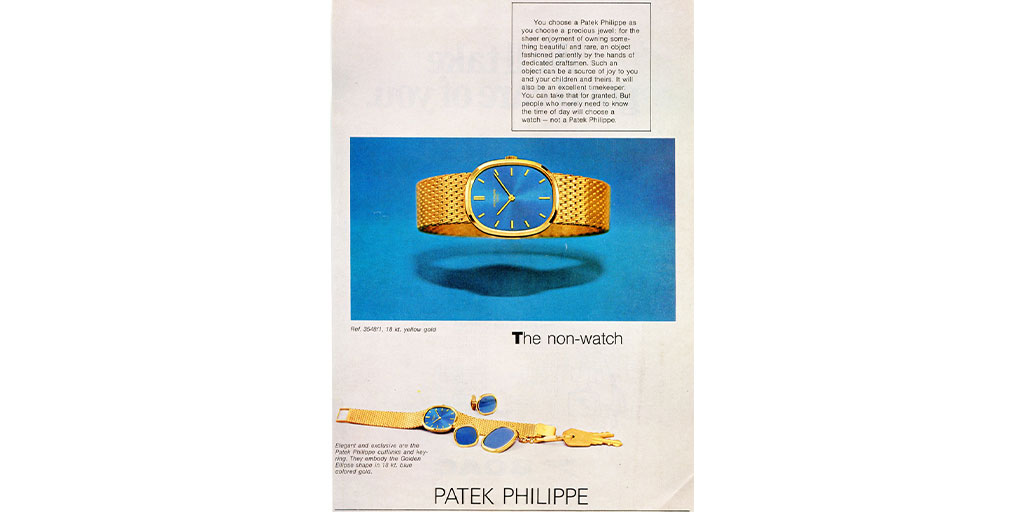

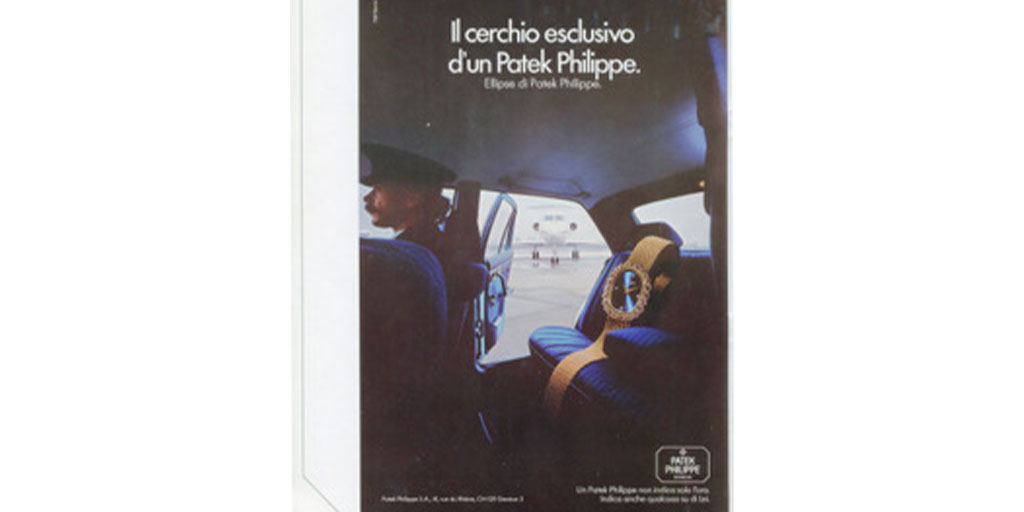

During the 1970s the Ellipse became the symbol of international chic. It was the timepiece the jet set had been waiting for and became a must have on the wrist of the best dressed men and women of the time. As Thierry Stern recalls from his childhood, “I thought of it as a piece to be worn by very classy people.” Its success was also due to the might of the Patek Philippe marketing machine behind it, and the model featured in most of the company’s advertising from the late 1960s through the early 1980s. The messaging of the Ellipse was as simple as the form itself. First, the watch was born of a classic design that was as ancient as the concept of beauty itself: the Golden Section. Second, the watch represented the ultimate canvas of design when exploring the craftsmanship of Patek Philippe. And last but not least, the Ellipse represented the ultimate icon of success and welcomed the wearer into an exclusive club, the club of owning a Patek Phillippe. So confident was the marketing of the stand-alone power of the Ellipse watch, that in a series of ads it was referred to it as “The Non-Watch”.

“You choose a Patek Philippe as you choose a precious jewel: for the sheer enjoyment of owning something beautiful and rare. People who merely need to know the time of day will choose a watch – not a Patek Philippe: The Non-watch” (Patek Philippe Ellipse advertisement, 1983.)

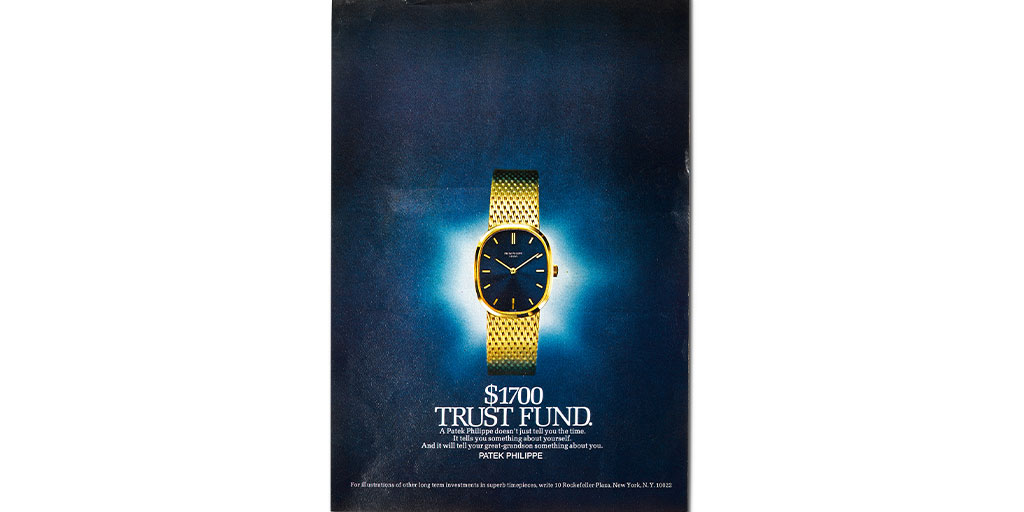

The company raced to meet demand with a broad selection of Ellipse and Golden Circle offerings to satisfy its clientele who wanted an alternative to the many quartz watches that were soon flooding the market. The solid demand for the Ellipse arguably helped Patek Philippe stay afloat during the difficult years of the 1970s and early 80s, as well as countless watchmakers, case makers and bracelet makers. So confident was Patek Philippe in the long lasting value of its finely executed design, that it even went so far in an advertisement from 1980 to describe a mesh bracelet Ellipse as a “$1700 Trust Fund”. This bold tagline was written by American ad man Seth Tobias who was responsible for some of the most innovative ads of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

Seth Tobias was the ultimate Mad Man from the wild and creative days of advertising in New York City during the ‘50s, ‘60’s and ‘70s. He struck up a close and extremely productive relationship with Einar Buhl the then head of the Henri Stern Watch Agency in New York. Buhl was also brilliantly creative and willing to take marketing ‘risks’ not seen in the watch world at the time. The results spoke for themselves as this really was a golden period for Patek Philippe and the US became the largest single market for the company. The eclectic and dynamic advertising behind the Ellipse no doubt helped.

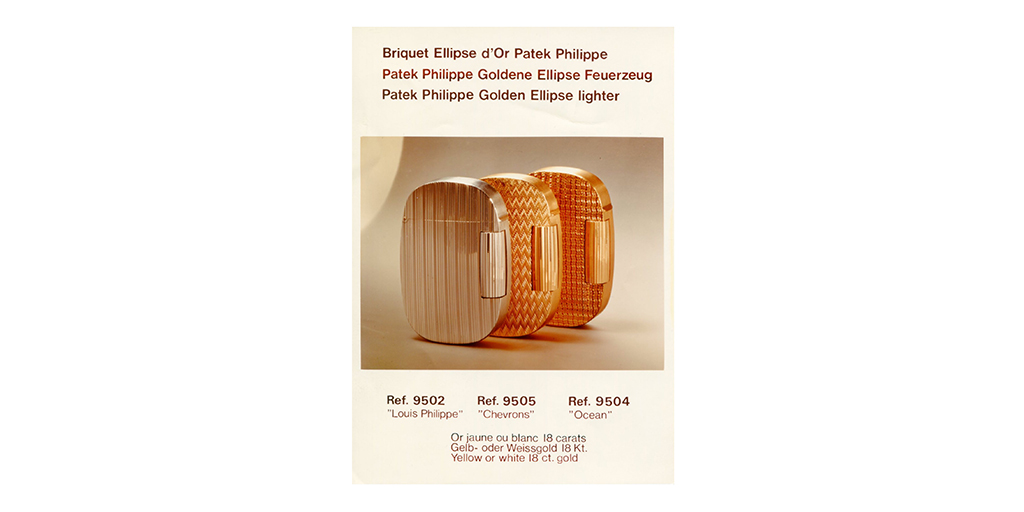

The testament to any great design is adaptability and for the first time in Patek Philippe’s history, it had a design that it could build a family and collection of accessories around. In addition to the Ellipse watch, there were Ellipse cufflinks, key chains, letter openers, clocks, tie clips and even disco-era, zodiac pendant jewelry. The design was literally a way to employ hundreds of skilled craftspeople who were otherwise losing their jobs due to the changing market forces of the quartz revolution.

Another accessory that recalls a bygone era was the Ellipse lighter. First produced in 1973, it was available in three guilloché 18K yellow or white gold finishes: a côtes de Genève called Louis Philippe, a weave pattern called Ocean and a chevron. Later came the now much sort-after enamel finished pieces available in red, blue and green. Each lighter and all of the Ellipse accessories were made with the same attention to detail and standard of exceptional craftsmanship as the watches. For more information on the Golden Ellipse lighter, please see this Collectability article.

The variety and volume of references from the Ellipse family and its close relatives is extraordinary. The Ellipse even eclipses the Calatrava in terms of the number of references and range of executions. By the end of the 1970s, Patek was producing a staggering, 65 different versions. Within the confines of this article, it’s simply not possible to review all the Ellipse collections that were produced from 1968 to today. Instead, we will look at some of the references we love most, and those that collectors are particularly keen to find.

In 1968, the collection started with references 3546 and 3548 which were listed in in the catalog until 1976. They were then replaced with references 3746 and 3748, each fitted with the caliber 215. The ultra-thin ref. 3589 was launched in 1970 and stayed in the collection until 1979. It was the first of Patek’s collection to use the LeCoultre base caliber 28 255, later to be used in the Nautilus ref. 3700.

One of collectors favorite models is the over-sized ref. 3605, also known as the “Jumbo Ellipse” made from 1971 to the early ‘80s. It also used the automatic caliber 28-2555 C (“C” for Calendrier) with date indication. The two piece case is 38 x 33 mm and 6.5 mm thick. The dials were made by Stern Frères, later Stern Créations, with the help of Singer who had mastered the blue gold and brown gold dials. It was made in 18K yellow or white gold with multiple dial and strap or bracelet variations. However, it is the strap version with the blue dial that has come to be seen as the classic, Ellipse model.

During the 1970s, Patek Philippe significantly increased its jeweled watches as demand exploded in this lucrative market. The ref. 3610 (early ‘70s) set with baguettes, and the ref. 3609 (1974) are good examples of these highly decorated and popular pieces. Both were fitted with the automatic caliber 28-255. However, as the trend for thinner watches continued, the calibers 175 and 177 were more often used. The manual references 3617 and 3620, launched in 1976, were popular mesh bracelet versions of this thinner, diamond-set look that so typified the glamour of the Jet Set ‘70s.

One of the longest running Ellipse references in terms of production is ref. 3738 which was produced from 1978 to around 2009. During its four decades of production, it was made with a myriad of dials and bracelet options. There were four main production series: First series 1978 -1988 with the caliber 240; Second series 1984 – 1999 with caliber 240 31; Third series 1999 – 2005 with caliber 240 111; Fourth series since 2005 with caliber 240 111.

The ultimate expression of the watchmaker’s art is the skeleton movement and what better canvas than the Ellipse case to showcase the skills of so many different craftsmen, especially the engraver. The first versions of the ref. 3880 released in 1980 had cases attached to a full lug to accommodate the typical 18 mm strap; later versions transitioned to t-bar lugs that could accommodate cut-out straps. It’s worth noting that in 1980, the ref. 3880 retailed for 8,800 USD, while a ref. 2499 perpetual calendar retailed for 13,500 USD. Only a handful of watches were produced each year until production stopped in the late 1990s. Today, less that 30 examples of the ref. 3880 are known to exist, only two of the early examples that accommodate full straps are known to exist. For a more in-depth study of skeleton watches, please read this Collectability article.

An interesting extension to the Ellipse family is the Golden Circle series. First introduced in 1971 as ref. 3604, it was discontinued in 1980. It remains the largest, vintage cushion-shaped watch after the Beta 21 refs. 3587/3597. The two-piece cases were 37 mm x 37 mm wide and 7 mm thick, produced in 18K yellow or white gold with several variations, including at least four different bracelet variations. As with many Ellipse models of this period, it housed the caliber 28 255 C.

Another Ellipse cousin is the enigmatic “Nautellipse” ref. 3770. Neither an Ellipse nor a Nautilus, it was introduced in 1980 and discontinued in the early ‘90s. At the time, Patek wanted to broaden the appeal of the best-selling Ellipse to an even wider audience and create a truly water-resistant, sports watch with an Ellipse case. Believe it or not, the Nautilus ref. 3700 was not selling so well at the time – it was considered too big and expensive, retailing for around 4000 USD. To make the ref. 3770 slimmer, a quartz E27 caliber movement was used with the word “Quartz” boldly on the dial. It’s easy for us to forget how impressive the accuracy and functionality of a quartz movement was at the time. The 35 mm x 39 mm cases for ref. 3770 were made by the same casemaker that made the ref. 3700: Favre & Perret located in La Chaux-de-Fonds. Like the Nautilus, it was made in a variety of designs, some with straps, most with bracelets and a wide array of dial options. Today, the ref. 3770 is also known as the “John Snow” – an enigma whose time will come. For more on the Nautellipse, please read this Collectability article.

Today, the only Ellipse in current production is the “Jumbo” ref. 5738 which was introduced in 2008 to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Ellipse when it was made in platinum featuring the classic blue gold dial. For the 50th anniversary in 2018, the ref. 5738 was released in 18K rose gold with a black sunburst dial. In addition, a special Rare Handcrafts version ref. 5738/50P with a white gold dial engraved with volute patterns, visible beneath a hand-enameled black layer was presented as part of a limited edition boxed set of 100 with matching cufflinks. All versions of the ref. 5738 are housed with the caliber 240.

The Ellipse no longer dominates the company’s production, but it’s importance to Patek’s identity is paramount. Even though the company has considered discontinuing the model, they keep it because, in part, as Thierry Stern said, “It’s like keeping a bit of the spirit of my grandfather.” We agree.

Photography credit: Collectability