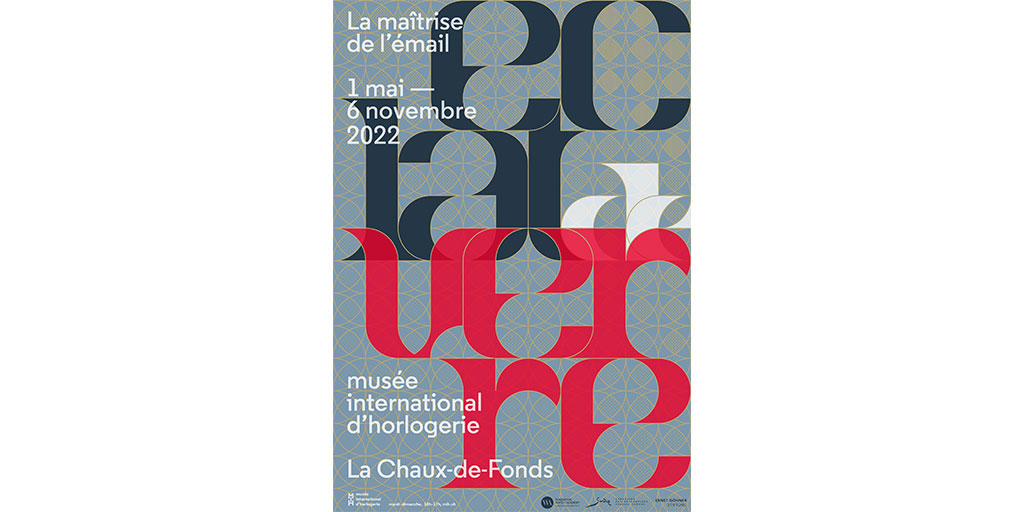

From May 1 until November 6, 2022, a special exhibition highlighting the history of the art of enameling will be held at the International Museum of Horology (MIH) in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland. For those of us not able to visit in person, read on as Carlos Torres gives a guided tour of this special exhibition.

Enamel has always represented a paradox. It is nothing more than simple glass elevated to its greatest exponent through fire, metal oxides and the expert skill of a master craftsman dedicated to this centuries-old art. They are the modern-day alchemists, lords of unwritten formulas, doomed never to stop learning over a lifetime of diligence. With the art of enamel, they are allowed to freeze time, capturing the moment of the completion of a dial or a case for centuries to come. Such is the power of glass and fire, so often extolled for their hardness and inalterability until one realizes that it is only a delicate material that requires the utmost care.

It’s been almost a quarter of a century since the world-renown Swiss “Musee International d’Horlogerie” of La Chaux-de-Fonds took a deep look into the art of Enameling. In 1999, the exhibition “Splendeurs de l ́émail. Montres et horloges du XVIe au XXe siécle” ran from April to September, displaying some of the most historically significant works of art using enamel as a base to enrich and decorate the dials and cases of clocks and watches.

Newly opened to the public on May 1, this exhibition “Éclat de Verre” (The Brilliance of Glass) draws on that same fascinating subject by displaying objects spanning from the 16th century to the present day. This time, however, the MIH decided to look through the maker’s lens, balancing the different styles and techniques with the history of this incredible art. This represents a unique opportunity considering this is also the commemoration of the International Year of Glass and the 150th anniversary of the “École d’arts appliqués” (School of Applied Arts) of La Chaux-de-Fonds.

By opening a class teaching painting on enamel as early as 1891, the School of Applied Arts was a pioneer in institutionalizing the training of this expertise. Initially reserved only for young girls, the emergence of the wristwatch and the decline in the market for enameled pocket watches decided the initiative’s fate by 1918. Following the closure of the class, only a handful of traditional manufacturers were able to preserve the art of enameling, ensuring its transmission to the ensuing generations.

Appreciation for enameling was only relatively recently reinstated in the new Millennium. This was due to the gain in popularity of decorated dials, strongly influenced by the interest in vintage and historically relevant timepieces. As a significant contributor to the exhibition through several works by former students, the school’s participation underlines just how rarefied the artisans of this art have become. From the artisan enamelers that created masterpieces, to those who commissioned them, the visitor descends into the unexpected simplicity of the raw material that stands in absolute contrast to the complexity of its mastery.

Although the origin of the art of enameling as decoration is uncertain, its roots point to the regions around the Mediterranean and China. But there is no proof that the art of enameling was practiced until after Alexander the Great (356 – 323 BCE), and then almost entirely in old Celtic areas that had become the northern provinces of the Roman Empire, and that persisted until the 12th century, particularly in Ireland. Between the 6th and 12th centuries, the art of enameling saw considerable development in the Byzantine Empire. At its height, and before it started to decline, craftsman created delicate and highly expressive miniature scenes in various colors. Copied by Lombard craftsman, it was imitated later in Sicily and in other parts of Italy.

During the Ottonian dynasty (ca. 919 – 1024), enameling flourished in eastern France and the Rhineland region until, supported by the courts of France and Burgundy, goldsmiths devised new and audacious methods of enameling that arose in the late 14th and the first half of the 15th century.

With the arrival of Huguenot artisans fleeing religious persecution in France during the 17th century, Geneva became one of the important centers producing enameled timepieces in Europe, a status it held until the end of the 19th century. It was the golden age of enamel, but the art fell out of favor at the dawn of the following century when watchmaking turned into an industry and focused on a more modest clientele.

Régis Huguenin and Nathalie Marielloni, Curators of the MIH, have undertaken an enormous task by organizing this exhibition with the help of their museum team. The display of more than 150 objects, many on loan by public and private institutions, represents a unique opportunity to experience pieces rarely displayed in public.

Pieces from the MIH collection and, for the first time, the school’s impressive collection of industrial arts, combine to allow a rare view into the techniques used to teach and pass on enameling expertise. Other contributors include the Museum of Art and History of Geneva, the Watch Museum of Le Locle – Château des Monts, the Cartier Collection, the Edouard et Maurice Sandoz Collection, the Patek Philippe Museum, as well as a number of manufacturing companies and independent artisans.

Exhibition Hall 1: Humble Prestige

Ever since timekeepers ceased to abide exclusively by their scientific and practical purpose, decoration became a fundamental means to enrich the almost magical aura emanated by the complexities of the mechanism within. Throughout history, wealth needed to be shown and to have an impact on others’ eyes. Artisans started to engrave and use precious stones and enamel as decoration to enrich timepieces. Often humble, modest individuals, many remained in the shadow of their patrons or employers, highlighting the striking contrast between the prestige collected by those commissioning the work, and the recognition granted to the artisans behind the creations.

Underlining the dichotomy between the owner and the artisan, the visitor to this exhibition first enters a hall in which 44 historic masterpieces have been selected for the technical mastery of their enameling, and their excellent state of preservation. The exhibits include personal items, owner’s portraits, pieces depicting Biblical, mythological and bestiary scenes, to signature pieces and works originally exported into far distant markets. Along with exquisite unsigned pieces, the exhibition displays works by the world’s finest enamelers such as Jean Limosin (Limoges), Henry Toutin (Paris) or Jean Petitot (Paris). A period spanning from the 16th to the mid 20th century, as is the case of a Patek Philippe Dome Clock produced by Michel Deville (Geneva), dates from around 1965 and is currently in the collection of the MIH.

Alarm, pocket and ring watches stand side by side with snuff boxes and exceedingly rare examples of artistic enamel work, as is the case of the famous mirror made by the Fréres Rochat of Geneva for the Turkish market. This particular masterpiece uses a mix of techniques such as champlevé, translucent enamel, and miniature painting and is on loan from the Musée d’Horlogerie du Locle in Château des Monts. World famous signatures complete this section of the exhibition including examples by Bovet, René Jules Lalique, Cartier and Pierre-Karl Fabergé.

Exhibition Hall 2: The journey to the furnace

Bringing metal oxides together with glass may sound simple enough, but the resulting enamel is in fact, highly complex and challenging to master and work with. It requires immense patience and meticulous attention to detail. With enamel, color depends on the addition of different metal oxides, like cobalt for blue, copper for red and zinc for yellow. These are then crushed in an agate mortar to reduce the components into an extremely fine mixture.

The Brilliance of Glass exhibition highlights this extreme skill and experience by covering the various steps of enameling techniques, from preparing its raw material, to the final firing stages. These also include the preparatory sketches used to obtain a template that allows the artisan to familiarize with every color, its’ opacity and at what temperature it fuses. Performing the role of artisan-chemist, the artist prepares their own color chart to catalogue the colors obtained after firing.

Regardless of the degree of expertise of the artisan, the exhibition highlights that no enameler is immune to unexpected adversities during the demanding process of firing. A single, unexpected moment can jeopardize days or even weeks of meticulous and detailed work. And although not wholly doomed, the possibility of retouching the work already done requires enormous skill. One piece in the exhibition highlights this challenge: a miniature painting by Henry Bone (London) made circa 1825 depicting the US president George Washington. A rare description by the artist on the back of the painting states that the enamel “cracked during the fifth firing”. The work is from the Victoria & Albert Museum and was made available to the MIH by the Rosalinde & Arthur Gilbert Collection. Additional works exhibited in this second area are by Henry Le Grand Roy (Geneva) and Danielle Wust-Calame (Geneva) among an array of other tools specific to the art.

Exhibition Hall 3: Enameling techniques

Enameling can be executed in many styles using various techniques developed over the course of centuries. The third part of the exhibition highlights the different methods of decoration that developed during the Renaissance specifically using the transparent qualities of enamel to full effect. Shown in this hall are 36 examples, most of them by unknown artisans or made by students of the École d’Art of La Chaux-de-Fonds.

These include champlevé enamel, cloisonné enamel, translucent enamel on guilloché, paillonné enamel, and miniature painting. Usually applied to an underlying guilloché pattern work, for example, “paillons” or “spangles” were used to highlight transparency and mirror the effect of precious stones.

Another example is the technique of “grisaille”, developed in Limoges in the 15th century, in which enamel is painted in shades of grey. It is a style that fell out of favor during the Renaissance to the rise of miniature enameled painting, designed to imitate oil paintings. Considered the most demanding of all the enameling techniques, painting on enamel and miniature painting were first introduced in the 17th century by master enamelers like Jean Toutin and Jean I Petitot.

Similar to oil painting, enamel powder is diluted to create colors and then applied on a carved metal surface to ensure optimal adhesion. If a colorless polished layer of enamel is used, this is known as the “Geneva” style. This “fondant” technique gives enamel an additional glossy under or overcoat, giving the work more significant depth and protection.

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, enamelers used the technique of fine miniature painting in enamels in Germany, Holland, England, and Russia providing the fashionable world of the society of the time. This section exhibits eight works from the late 19th to the first quarter of the 20th century. Among unknown authors and students of the École d’Art, La Chaux-de-Fonds, one can find a set of enameled portraits by Henry Capt (Geneva), and a work by Etienne-Marie-Alfred Garnier and Paul Grandhomme, executed in 1893, masterfully depicting Shakespeare’s Desdemona.

Exhibition Hall 4: Avenues for transmission

The fourth section of “The Brilliance of Glass” exhibition examines the teaching processes and the importance of the ongoing, exploratory nature of enameler’s training. Drawing on the 150th anniversary of the “École d’arts appliqués” of La Chaux-de-Fonds, founded by master engravers facing a shortage of qualified workers to decorate watch cases, the MIH seeks to understand the strategies employed by artisans to preserve a degree of secrecy in the creation of enamel recipes.

At the same time, the museum looks at the importance and continuity of mentoring in the training process. To this problem, the MIH states the following in its exhibition brochure: “The private micro-structures which prevail today often do not allow independent artisans to join their students. In the absence of complete courses in art schools, private initiatives are offered, giving an introduction to enameling or short, continuous professional development courses providing certification. These are frequently taken by artisan engravers or jewelry-makers who want to develop their practice. The Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry offers in-house company training leading to a two-year enameler’s diploma. It is currently provided by the Richemont Group for a handful of students, serving the needs of several brands.” The text refers to the Campus Genevois de Haute Horlogerie, located in Meyrin, with four items on loan in the exhibition.

Presenting a selection of 21 works produced by students of the “École”, the museum tries to underline the paradox between the high value of enameled objects and the absence of well- established apprenticeship routes. Knowledge of enameling techniques is scarcely passed on and may be attributed to the extraordinary demands of the profession and its training, which require a long apprenticeship involving much experimentation. The choice of raw materials, restricted by the dwindling number of glass manufacturers, has also contributed to the nonproliferation of the art.

At the same time, and in the 21st century, the craft faces challenges remaining at the mercy of the misuse of the term “enamel”, which is sometimes refers to products made with synthetic resin, acrylic, varnish or lacquer. To shed some light on this reality, the MIH decided to show four portraits of independent enamelers filmed in their working environments by director and ethnologist Sélima Chibout.

Also on display, and lent by the State of Neuchatel, is a historical collection of notebooks containing enameling recipes and procedures written in the late 18th – early 19th century. The manuscripts, by Louis Benoit, provide evidence of how they were perfected and the need to maintain the utmost secrecy concerning some of them. To do this, Louis Benoît went to great length and created his own coded alphabet.

This fourth section of the exhibition includes works made between the late 17th century and the present day by master enamelers like Pierre Huaud (1612-1680), the first known enameler in Geneva, Jules Amez-Droz, Walter Stucky and Debora Martinez. Master enameler Anita Porchet is represented through two of her works made for Hermès in 2013 and 2017.

The centerpiece of this part of the exhibition is the enamel masterpiece co- signed by Carlo Poluzzi (1899-1978) and Suzanne Rohr (1939), recently acquired by the MIH. A pocket watch with a minute repeater and perpetual calendar, made by Patek Philippe and dated 1966, comprising two paintings on enamel signed Poluzzi-Rohr on one side and Rohr-Poluzzi on the other. This co-signed piece marks a historic accomplishment for Suzanne Rohr, who was mentored at the time by Carlo Poluzzi. Initiated into the world of enamel at the age of 15 as an apprentice in the Geneva Enamels manufacture, Carlo Poluzzi quickly acquired total mastery of painting on enamel. While barely in his twenties, he became director of the enameling workshop and worked for top watchmaking brands like Patek Philippe and Vacheron Constantin.

Born in Geneva in 1939, Suzanne Rohr trained as an enameler and enamel painter, obtaining her diploma in 1959. Unable to find a place to work, she opened her own workshop where she created enameled jewelry from 1960 to 1967, after which she met Carlo Poluzzi, who became her mentor for the next 28 years. During this time, and after refining her technique Suzanne Rohr dedicated herself entirely to enamel miniatures.

Among the generous loans by private institutions to this exhibition, the Patek Philippe Museum contributed six items, three of them with fascinating shapes cases dating from 1810, 1815, 1825 and 1880. These are part of a series of extravagant timepieces made for women in the 19th century.

The first has a case in the form of a knife in engraved chiseled gold, translucent enamel on guilloché and champlevé, and decorated with paint on enamel and pearls. Painted on enamel on gold is a scene depicting a landscape with a castle on the front and a landscape with a windmill on the back. The second item is a pendant watch with its case in the form of a shepherd’s dog and lamb in engraved chiseled gold, champlevé enamel, and decorated with paint on enamel and pearls. The third is an enameled pen in engraved, chiseled gold, champlevé and translucent enamel on guilloché with pearls. The fourth is a Lorgnette with a watch, richly decorated with blue champlevé enamel. The case of this magnificent piece protects a folding lorgnette which can be removed using a push-button on the side. On the cover, a medallion with paint on enamel features two young girls dancing in a garden; the sparkling effect of the translucent enamel on the guilloché background for the costumes contrasts with the subtle colors used for the greenery.

Also on loan from the Patek Philippe Museum, is a pocket watch from circa 1820 by the Huguenot Ravené, established in Berlin. The timepiece has a gold case decorated with a map of Prussia and the Baltic Sea in champlevé enamel. The bezel is covered with black champlevé enamel on gold and adorned with gold flourishes and motifs. The exquisitely detailed map from an unknown master must have required extraordinary skill from the engraver, using a chisel to cut the recesses to be filled with enamel while preserving the delicate outlines of the letters spelling out the names of the cities and rivers.

Two further pieces produced by Patek Philippe are on loan from the Patek Philippe Museum. The first is a pocket watch in gold and enamel (miniature painting by Luce Chappaz) depicting the old bridge over the Swiss Vièze river, dating from circa 1970. The second is a crisp and magnificent Ref. 5131R wristwatch from 2015, the dial center decorated with a map of the world in cloisonné enamel, part of its World Time collection.

This is an unmissable exhibition highlighting enameling in all its finery by covering the past and present challenges in training a new generation of enamelers. It successfully achieves its objective of communicating the vulnerability of this rare expertise and its transmission in the face of the growing industrialization of the watchmaking arts.

The exhibition “Éclat de Verre” (The Brilliance of Glass) will receive visitors until the 6th of November 2022.

-Collectability recommends listening to the Podcast episodes with MIH Deputy Director Nathalie Marielloni and Master Enameller Anita Porchet.