At Collectability we love treasure hunting, and we particularly love pocket watches. Visiting Alex Ku’s collection of pocket watches on show at the Horological Society of New York’s elegant library is a happy combination of both.

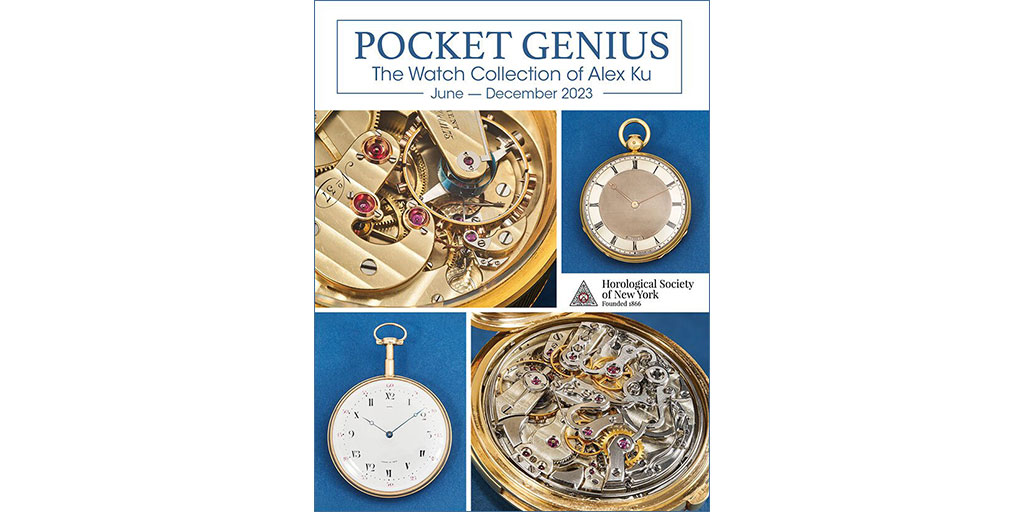

In seven short years, Alex Ku has amassed an impressive collection of pocket watches that span over 300 years of important horological advancements. The exhibit comes to an end in December, and we strongly encourage you to visit if you are in the New York area. A visit to HSNY will also enable you to explore the incredible Jost Bürgi Research Library which is among the largest horological libraries in the world with over 25,000 items on the study of time and timekeepers.

Inspired by his grandfather who designed machine tools, Alex Ku decided to study physics which in turn led him to appreciate mechanical watchmaking as a science. Researching the history of horology, he began to appreciate the genius of watchmakers such as Graham, Mudge, Berthous, Lepine, Breguet, Arnold, Fasoldt, Philippe and Audemars. By collecting pocket watches made by these and other genius watchmakers, Alex was able to understand how the English, American and European horologists developed the technology which shaped the watch industry from the 1700s to today.

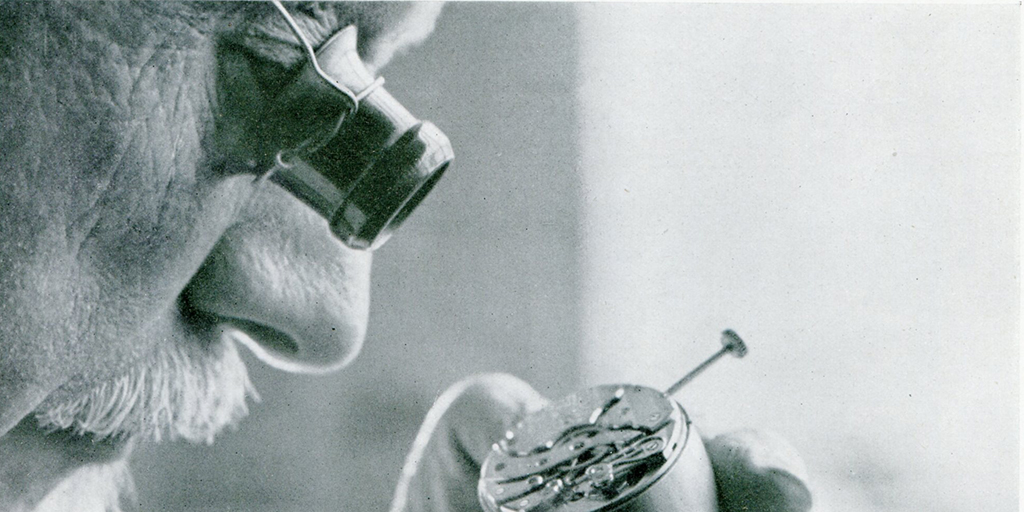

I asked Alex what advice he would give to a collector new the world of horology and particularly pocket watches and he suggested, “read at least one classic book on timepieces, such as ‘Watches: A Complete History of the Technical and Decorative Development’ by George Daniels and Cecil Clutton. This is to enrich his/her mind with ideas of what has been ‘invenit et fecit’ in history. To think of what are their most interesting timepieces, most appealing mechanical inventions, styles & decorations.” The concept of ‘invenit et fecit’ – ‘invented and made’ – was very much the corner stone of his own collecting strategy. As Alex explains, “I set my goal to collect watches so that I’d rejoin those names that appeared with ‘invenit et fecit’ for better precision watches. They are rarely mentioned nowadays (unless some was revived such as Ferdinand Berthoud) but should not be forgotten. And I like to illustrate their inventions and style influence on other watchmakers.” ‘Invenit et fecit’ denotes that a company or watchmaker designs and builds the entirety of the watch movement. This rarely happens in the world of watchmaking today so it is a pleasure to see watches built by the person whose name appears on the movement.

Following this goal for collecting, Alex Ku focused on four areas: pieces crafted by eminent historical watchmakers, the rarest escapements, the most intricate complications, and unique aesthetics. The exhibit at HSNY follows this strategy and the pocket watches are presented in four sections accordingly.

The Historical Makers section includes timepieces by some of the most important watchmakers of all time. The earliest watch in the exhibit is in this section and was made by Daniel Quare (1649-1724) in 1690 (see above). This magnificent piece has a silver champlevé dial within a decorated tortoiseshell case. Quare was a contemporary to Thomas Tompion (1639-1724) the ‘Father of English Clockmaking’. Quare is credited as the inventor of the repeating pocket watch movement, an honor he received from King James II. The late 1700s through the 1800s was an extraordinary period for timekeeping advancements and beautiful examples of the work of George Graham, Mudge & Dutton, the Leroy dynasty, Jean-Antoine Lépine and Abraham-Louis Breguet can be seen in the vitrine for this section.

A doctor’s watch (or captain’s watch) by John Arnold is interesting to see as it is an early ‘hacking watch’ which has a balance that can be stopped to synchronize with another timepiece (see above). It has a relatively small dial for hours and minutes, and a large seconds indicator for timing a patient’s pulse. John Arnold was a pioneer of marine and pocket chronometers and later became renown for working on the longitude problem and how to tell the time at sea.

Alex Ku’s interest in the evolution of precise timekeeping encouraged him to collect important escapements. During the mid to late 1800s, American watch companies were producing the finest watches in the world, and American railroad-grade watches, known for their reliability and accuracy, were in high demand. Two of the best-known American watchmakers from this period are Charles Fasoldt (1818-1898) and Albert Potter (1836-1908), and it’s particularly interesting to see two very fine pocket watches by these watchmakers in this section (see above and below).

Nowadays, Swiss watchmaking is regarded as an important leader in the world of horology so it’s hard to imagine that during the 1800s, Swiss watch manufacturers copied some American designs and began producing watches which superficially resembled American railroad-grade pocket watches, but which were of lower quality and sold at a much lower price. Many of these watches had names which closely and deliberately resembled the names or initials of American manufacturers and watch models. For example, Elgin was copied as “Elfin” and Waltham’s “A.W.W.Co” became “B.W.W.Co”. These pocket watches became known as ‘Swiss fakes’, none of which can be seen in this exhibit!

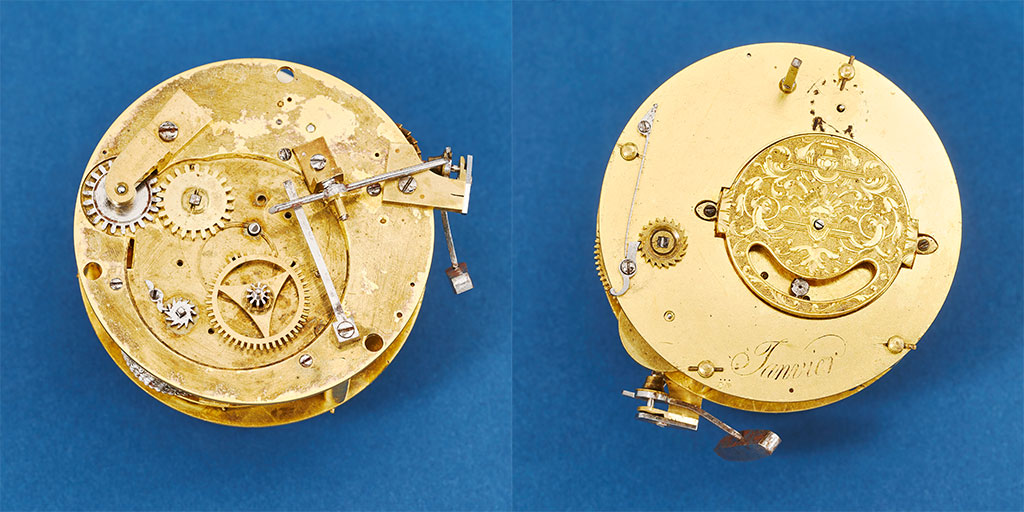

The Escapement section includes a movement by Antide Janvier (1751-1835). At Collectability, we are big fans of Antide Janvier, a genius maker of precise and complicated clocks. One of the very few non-Patek pieces we have sold was a museum-quality exception: the first clock made by Janvier when he was just 17 years old. The movement in this exhibit was probably made by Janvier around the same time and is a small masterpiece.

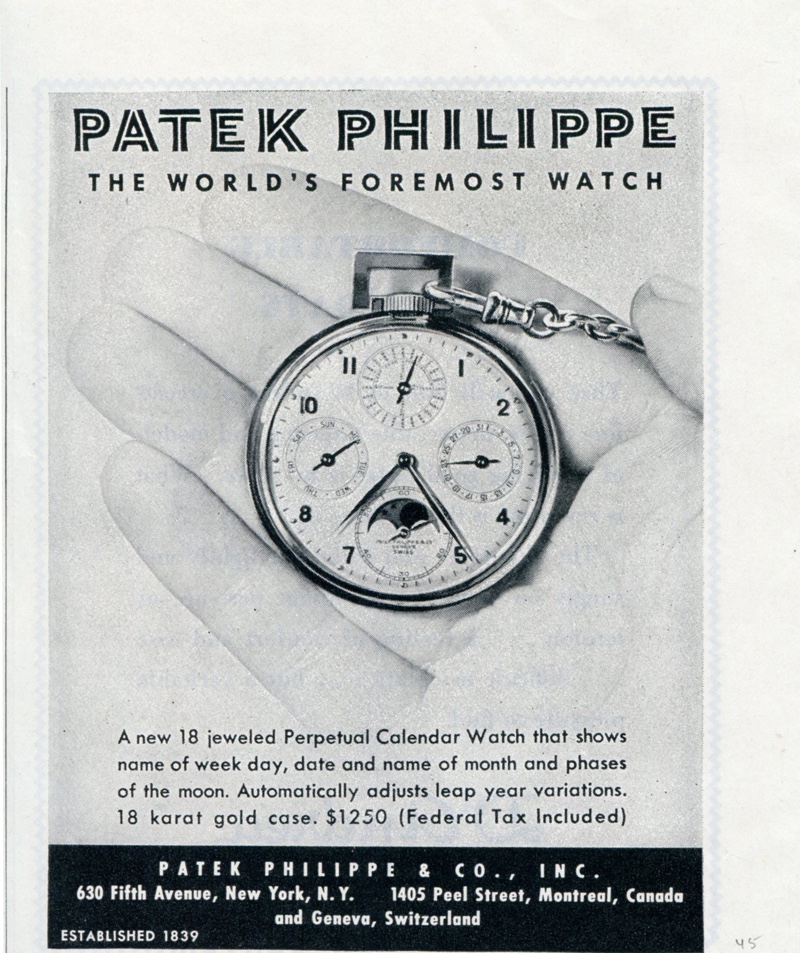

One of the highlights of the Complications section is not surprisingly a split-seconds chronograph made by Patek Philippe. The pocket watch in the exhibit is an early example of this complication by Patek and was sold to Tiffany in 1890.

Another interesting piece in the Complications section is the montre á tact by Henry Capt circa 1880 (see above). The montre á tact pocket watch has an additional hand on the hunter case cover so that the time can be ‘read’ by feeling where the hand is in relation to raised hour indicators on the side of the case. This was a useful invention not only for the visually impaired but also for the pre-electricity days when nighttime light was limited by candles.

The Aesthetics section holds the most Patek Philippe pocket watches on display and was particularly appreciated by the Collectability team. One of John Reardon’s favorite pieces in this section is a pocket watch sold to “ H. Norman Snively 1920”. Snively was a geologist for the Standard Oil Company and other companies and published mining reports on uranium and other minerals. This timepiece has radium hour makers which were applied after Snively purchased the watch, presumably to help him see the time when exploring poorly lit mines. Fortunately, the HSNY librarian, Miranda Marraccini regularly checks this timepiece with a Geiger counter to make sure the radium markers remain at a safe level for visitors.

My personal favorite is a double-sided enameled pendant watch made by Patek Philippe in 1850. The extraordinary miniature enamel scenes, one of a landscape and one of flowers can normally only be seen on a watch in a museum. This timepiece happens to also be Alex Ku’s favorite Patek Philippe and he explained to me that he purchased the piece from the original owner’s family who live close to Manhattan. The watch was originally made in 1850, but not sold until 1855. Alex likes to think that “Mr. Patek may have brought this watch in the luggage during his journey to the USA and found its buyer.” It’s a romantic thought that this watch may have been personally delivered by Antoine Norbert de Patek when he visited the USA to secure new business opportunities.

Why collect pocket watches? Alex Ku recommends three main reasons for collecting pocket watches. First, rarity: “pocket watches could be [considered to be] more exclusive collectables, even compared to ‘limited edition’ wristwatches.” He says, “some inventions and art-styles were produced as prototypes or in a minimum quantity, whereas some watchmaker’s works may be scarce because most of his production was lost/damaged through a long time of 2-3 centuries… some pocket watches may be possibly unique, or fair to say made in less than 10 pieces. This may give the collectors a better feeling of achievement and satisfaction (than having a watch that differs only in color or case-material).” Secondly, treasure hunting: Alex believes that pocket watches “can be perfect objects for treasure hunters, and would not frequently cost a big fortune,” which he thinks is a major fun factor of treasure hunting. Thirdly, education: Alex believes that “the pocket watches offer the collector a great opportunity to explore different aspects of watches. To name a few, complications such as minute repeating and split-chronograph etc.; top notch hand-craftsmanship, presentation and finishing, luxurious decorations such as enameling.”

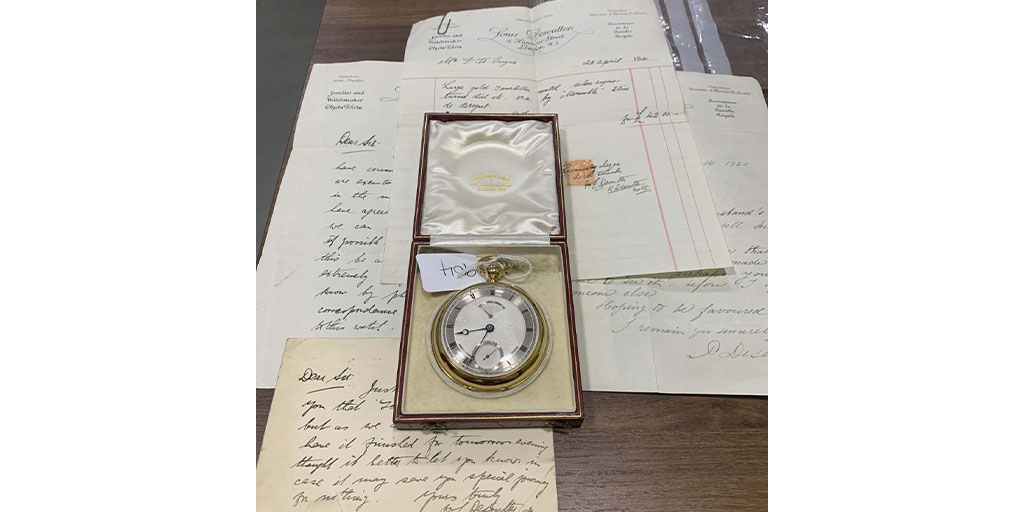

Alex’s overall favorite pocket watch in his personal collection is the ‘régulateur à tourbillon’ made in Breguet’s workshop during the 1820s (see image above). The watch came with excellent paperwork proving its provenance which were preserved from its last sale in 1930 from Louis Desoutte’s store in London. “This watch is the rarest technical wise, and I can’t ask for more given its provenance.” This watch was not included in the Pocket Genius exhibit, but Alex hopes to exhibit it in the future.

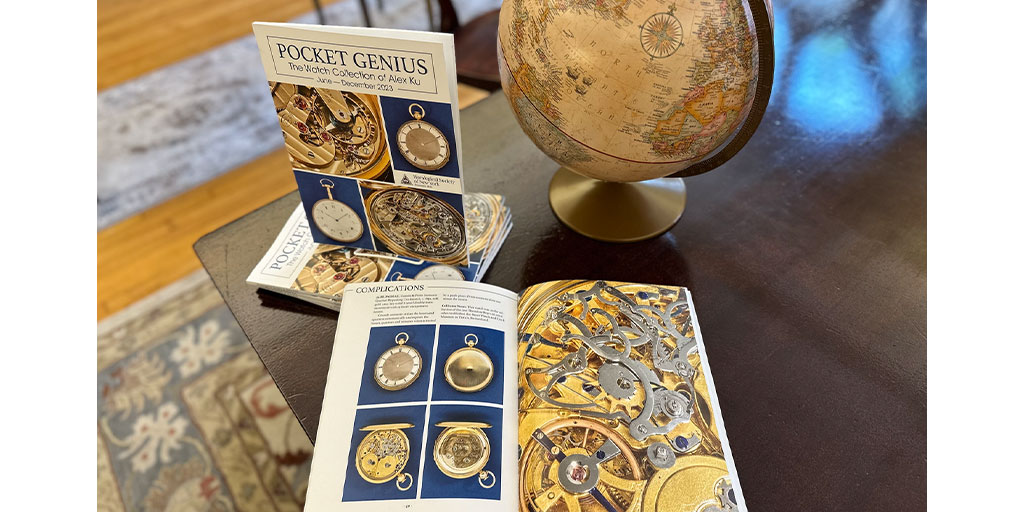

It is worth noting that Alex Ku will be available at the exhibition to personally answer any questions visitors may have between December 6 – 11 when he will be visiting New York to attend the watch auctions. Hopefully, you will be able to visit in person, but if not, the HSNY has published a superb catalog of the exhibition in which the collection is divided into ‘Historical Makers’, ‘Escapements’, ‘Complications’ and ‘Aesthetics’ with stunning images by Atom Moore. The catalog is available free on line, but I encourage you to pay $20 + shipping and enjoy the beautiful images and have it as a reference for your own horological library.

October 2023

Collectability thanks the Horological Society of New York for use of its images.