When the Patek Philippe Museum opened in 2001, visitors were blown away by extraordinary animations that brought the intricate, magical world of mechanical automata and the inner workings of a Patek movement to life. Only a watchmaker had ever seen inside this secret world and now it was clearly on view for all. Most importantly, the animations were presented in such a way that any viewer, no matter how limited their horological knowledge, could clearly understand just how these marvels worked. No one had done that before. As we watched in awe, and I count myself fortunate to have been at the Museum opening night, none of us gave a thought to the person responsible for the innovation in animation that we had witnessed. Until now.

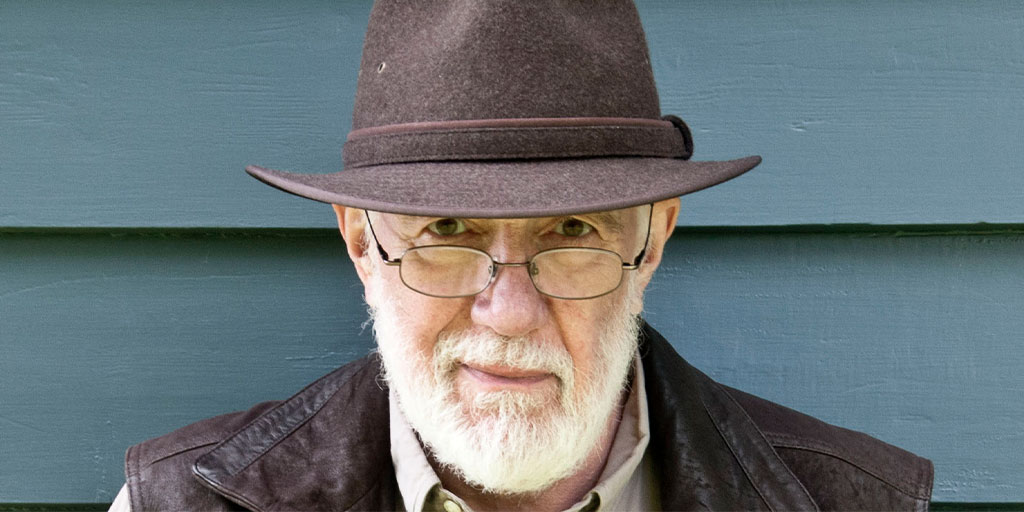

We recently learned that John Redfern, the man responsible for the Patek Philippe Museum animations and many other museum and horological presentations, had sadly passed away at his remote home studio in Scotland. John Redfern had a unique resume: he began his career in film making and then became a highly regarded clockmaker and restorer. These two talents, combined with his passion for animation, photography and technology led him to become a pioneer in the world of horology. In an effort to learn about this anonymous artist, I had the distinct honor to speak with several icons of the world of horology, all of whom agreed to speak exclusively with Collectability because they had worked with John and had the same thing to say: “He was a horological genius”. Here, in their own words is the story of John Redfern.

Alan Banbery, former Patek Philippe executive director, curator of the Patek Philippe Museum and author

Alan Banbery is one of the legends in the world of Patek Philippe. He spent many years working closely with Philippe Stern collecting and curating an unprecedented collection of timepieces which would become the Patek Philippe Museum. When working on the creation of the museum itself, Alan Banbery had the vision to employ John Redfern to make a series of animations to explain a selection of exquisite pieces and an iconic Patek movement.

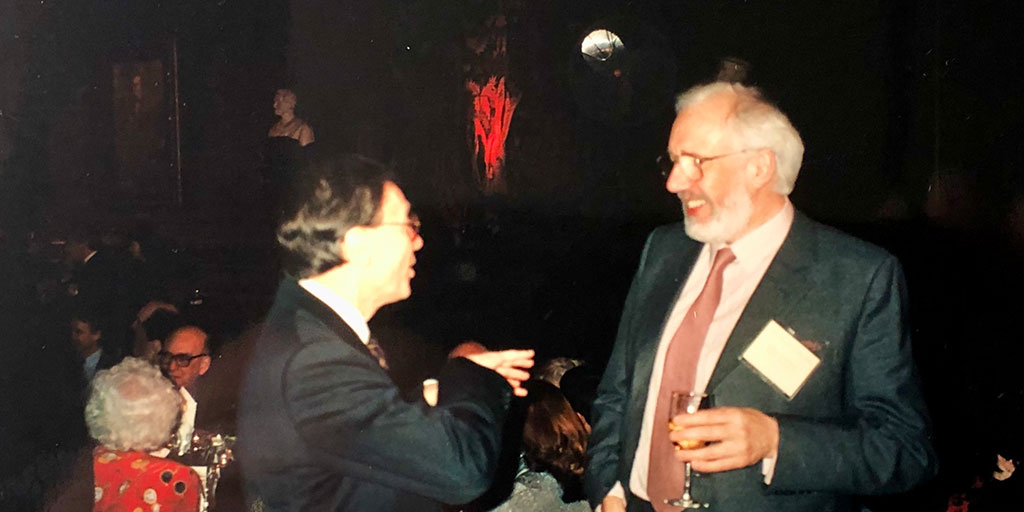

“I believe it was Will Andrewes who first brought my attention to John Redfern’s exceptional talent which, at the time, was unique. Will said that I should view a video made of an ‘animation’ presentation which John had made for the Longitude Symposium at Harvard University in November 1993. Having duly viewed the video in question, I formulated the idea that a few, very complex pieces in the Patek Philippe Museum collection could, possibly, be highlighted with such brilliant animations. I then approached Philippe Stern and, having also shown him John’s video presentation, outlined my idea in more detail. With Philippe Stern’s inherent flair and vision, he agreed we should invite John Redfern to Geneva and arrive at an agreement for him to produce some of his animations for the Patek Philippe Museum.

My first personal contact with John Redfern was by telephone to his home in Scotland. Needless to say, John was enthusiastic at the prospect of working for Patek Philippe and shortly thereafter, in November 1997, arrived in Geneva for his meeting with Philippe Stern and myself. From then on, John and I worked exclusively together. Naturally, various stages of each animation were shown to Philippe Stern who was keenly supportive throughout the project. John was an exceptional and talented craftsman. I never doubted his horological talents, and certainly had no qualms in entrusting him with the ‘Moses’ pocket watch or the ‘Singing bird’ pistol, both masterpieces of automata!

After the official opening of the Patek Philippe Museum in 2001, John Redfern and I remained in contact. At one stage, John beautifully restored an antique longcase year-going clock which belonged to a friend of mine. The work he carried out on this timepiece was complex, and even included some fine marquetry work John restored on the cabinet!

Needless to say, I was greatly saddened to learn, from Maxine his wife, that John had suddenly died due to a heart-attack.”

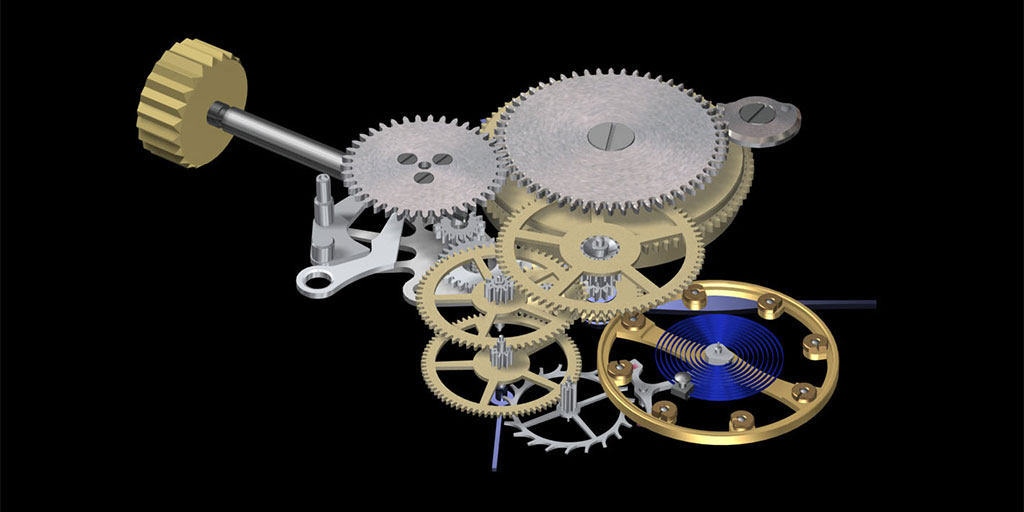

John Redfern started to work with Alan Banbery on the animations for the Museum pieces in the Spring of 1998 and completed four films over several years. His first film was to explain the mechanics of the caliber 215 manual winding movement. Nowadays we are used to seeing the inner workings of a movement, but in 1998, this was a novel insight and the first time that non-watchmakers could appreciate the marvel of a Patek movement.

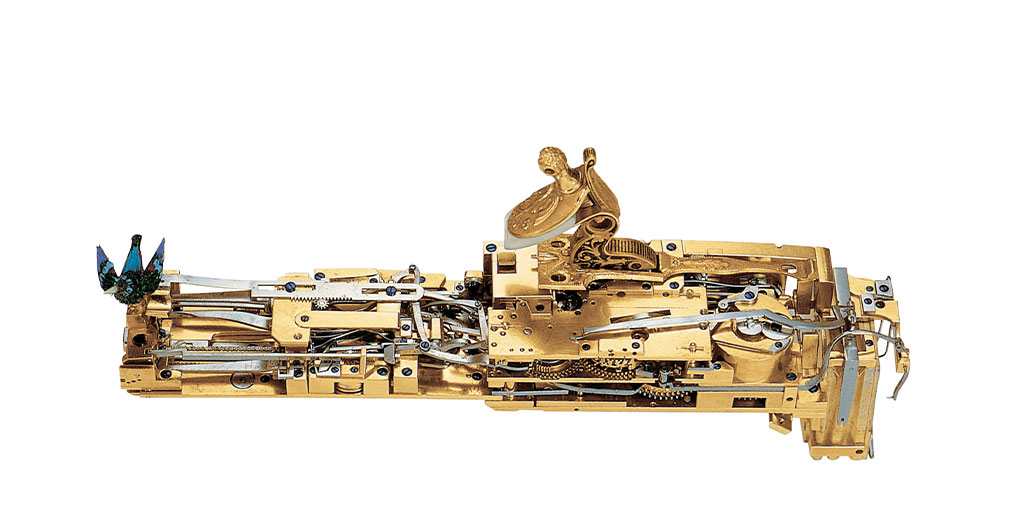

In 1999, John created the animation to explain the brilliant automaton movement inside the ‘Moses’ pocket watch (circa 1815. Attributed to Dubois au Locle). When wound, Moses strikes the rock and water flows out, he turns his head to observe his followers drinking from the stream thanks to the miracle. It’s not hard to imagine how extraordinary this timepiece must have appeared to the first privileged viewers in the early 1800s. Even for us today, it is still an awe-inspiring, mechanical achievement. Thanks to John Redfern, we can understand how it works. The same can be said for the beautiful ‘Singing-bird’ pistol (circa 1815. Attributed to Rochat Frères & Meylan). However, this was an even more challenging project. According to John on his website, “This was one of the most complicated projects I have undertaken, and it tested both my watch-making and animating skills. The mechanism, which is tightly packed in an elaborately decorated case of just 15 cm length, had to be dismantled and many repairs done before the drawing and modelling of some 500 components could begin. Only then could I start telling the story and animating the mechanism to explain all the movements of the bird and its song. The whole project took over 2000 hours.”

Another project, arguably even more complicated was the three films that John produced to explain the Dates of Easter, Sidereal Time and an explanation of the 19 hands and many dials of the then most complicated timepiece in the world, the Calibre 89. John was fortunate to have an early prototype of the movement in his studio to work with, plus he spent “many enjoyable hours at Patek Philippe with M. Paul Buclin, the master watchmaker responsible for finishing and putting the watch together. He spoke no English, my French is very poor, but the love of what we were doing transcended that.”

All of John’s animations for the Patek Philippe Museum are available on DVD directly from the Museum.

William J. H. Andrewes, master horologist and creator of the Longitude Dial

Will Andrewes is one of the world’s leading horologists, historian, clock conservator, museum curator and consultant, inventor, artist and sundial maker. He is also a great connector of people and his name repeatedly pops up in connection to John Redfern as he introduced him to most of his most important commissions (as we learnt above from Alan Banbery). Will started his career working with the iconic watchmaker George Daniels; he then spent ten years at The Time Museum and in 1987 became Curator of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments at Harvard University. It was during this time that Will first worked with John Redfern.

“In 1993, I organized the Longitude Symposium at Harvard to help redefine the world’s understanding of John Harrison’s role in the history of time. [the symposium also inspired Dava Sobel to write ‘Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time’ (1995), arguably, the best-selling horological book ever written.] For his Longitude Symposium talk “The Timekeeper that Won the Longitude Prize”, Anthony Randall had commissioned John to create an animation to explain how the remontoire and the escapement of Harrison’s fourth marine timekeeper (H4) worked. The animation was a huge success with many attendees saying it was the first time they truly understood the remontoire. This was the genius of John Redfern; he could make something extremely complicated easy to understand because he had the unique combination of a talented clockmaker and animator. He had the experience and ability to understand complex movements and the skill as a communicator and artist to condense and explain them. Through his training as a clockmaker and restorer, he was particularly interested in chronometers and because he was such a meticulous person, dedicated to understanding mechanisms, he could take on any horological project such as the extremely complicated pieces for the Patek Museum. John was always breaking new ground, looking for new technology that could push his animation and photography further. He was a pioneer in animated horology and happiest when he could use his skills to educate.”

More about John’s animation of the Harrison clock for the Harvard symposium can be seen here.

Philip Whyte, Past Master of the Clockmaker’s Company and co-owner of Charles Frodsham & Co.

Philip Whyte has been involved with watchmaking for over 50 years and is one of the most respected and eminent members of the horological community. Philip has worked with John as a clockmaker and restorer as well as an animator for his own fine watchmaking company Charles Frodsham & Co. He had known John and his wife Maxine for many years and John was completing a project for Frodsham when he unexpectedly passed away.

“John was a gifted clockmaker and restorer. I first got to know him many years ago when we compared notes on the restoration of Hardy regulators. He had restored two regulators by Hardy, the pallets of which can be extremely taxing to repair properly. It’s only more recently that we worked with John as an animator, in fact his last three jobs were for Frodshams. He passed away a busy man, working right up until the last moment, which is certainly how he would have wanted it. His special skill, was in combining two major disciplines: clockmaker and animator. There exist many good clockmakers, likewise many good animators, but I don’t know of anyone who combined those two disciplines so effectively. That was his special talent, he could walk in the shoes of a watchmaker and understood what needed to be explained, and then with his animators’ hat on, clearly and effectively animate the mechanics to a non-technical viewer.

Additionally he had another skill set to put into the mix, in his early career, he was employed as a film editor by the Rank Organisation, working on films such as Spartacus. So from early on, John fully understood the visually seductive nature of ‘moving pictures’ being able to connect with an audience.

He was also skilled as a communicator, which is why he could make something complicated easy to understand. He was very good with people; gentle, charming and interested in many subjects. If you were stuck on a desert island, you’d be happy that he was there with you, you would never run out of conversation, and he might just come up with a solution to get you both off the island!

We, at Frodshams, will sorely miss his visits to our workshops.”

Dr David Bisno, retired ophthalmologist, lecturer in lifelong learning and founder of the Bisno Schall Clock Gallery, Santa Barbara

David Bisno, M.D., a retired ophthalmologist with an interest in the history of horology, was teaching a course, ‘It’s About Time’ to retirees in Santa Barbara when his class was invited to visit the Santa Barbara Courthouse, home to a tower clock. The weight-driven, double, three-legged, gravity escapement masterpiece was manufactured by Seth Thomas in 1929. The clock had been hidden from public view behind plywood walls since its installation 82 years prior. David and his wife, Fay, envisioned turning the space in which the clock was sitting, into a gallery of horology where visitors could admire the ingenious instrument and learn its place in the history of timekeeping. David and Fay prevailed upon Dick and Maryan Schall to be co-benefactors and immediately set about gathering a group of volunteer experts. Will Andrewes, as the Gallery’s consultant, knew how to locate John Redfern who agreed to make a video-animation explaining how the tower clock worked so that guests visiting the room would better understand the genius of the clockmakers.

“After seeing John’s animation work at the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva, I knew I wanted a video of this quality for the Clock Gallery. After learning from Will Andrewes in Santa Barbara that it was John Redfern in Scotland who had done the videos for Patek, Will helped me contact John. I discussed our project with him. I learned we would have to raise a significant amount of money. Fortunately, Ed Birch of the Mosher Foundation in Santa Barbara appreciated the beauty of a Redfern video and immediately wrote the necessary check. Thanks to John’s extremely easy-to-understand video presentation and the narration which I and my horology colleagues added, every visitor to the gallery is able to learn the mechanics behind the ticking, swinging and ringing. The special genius of John’s work: making visually clear for lay audiences an understanding and appreciation of a fine instrument of time keeping. ”

See John Redfern’s animation for the Santa Barbara tower clock here. Visit the Bisno Schall Clock Gallery here.

Mostyn Gale, Santa Barbara Courthouse Clock Master, conservator and restorer

Mostyn Gale was the conservator who led the restoration of the Seth Thomas tower clock. In 2010, the clock had stopped and Mostyn was in the process of disassembling the clock, measuring and photographing every single part.

“It was fortuitous that we were restoring the clock at the same time as John started working on the animation. We were cataloguing in detail every single component and this information could then be emailed to John to help him with his preparations. Because John was an accomplished clockmaker, he could completely understand every working detail of the tower clock and had all the information he needed for the animation without ever having to visit Santa Barbara. John was also extremely curious and wanted to learn even more about the clock and he encouraged me to conduct some experiments, for example to see how long the pendulum would swing without impulse (8 hours), to demonstrate how little energy was needed to keep a 175 lb pendulum going. In order to make the animation as realistic as possible, John asked me to take pictures and describe in detail the various textures of certain clock parts. He did a stellar job explaining the complications of a clock movement in a clear and concise way to non-mechanical people.

A few years later, I was fortunate to visit John’s home studio in Scotland. Although a remote location, John had transformed an old carriage house into state-of-the-art studios. He had separate workshops for clockmaking and restoration; woodworking (to repair clock cases); a computer studio with the latest animation technology; a photography studio with various cameras for close-ups and panning and a library full of horological books. He was completely self-contained and obviously lived a contented life with his wife Maxine.”

John’s interest in animation began because he wanted to explain timepiece movements as close to their 3D reality as possible. With virtual reality, levers and wheels that would otherwise block a key mechanism can be stripped away so that the focus and understanding is where it needs to be. In this animation, John Redfern explains how animation is the ‘art of the impossible’ and the world of a pocket chronometer is revealed. Now we take such images for granted, but it’s worth remembering the innovative genius of John Redfern who opened this world to us all almost thirty years ago.

Very special thanks to Alan Banbery, William Andrewes, Philip Whyte, David Bisno and Mostyn Gale for generously speaking with Collectability about John Redfern and the important legacy he has left behind.