The day before I spoke to John Reardon, he had been keeping an eye on — from his home in New Jersey — the Phillips Geneva Watch Auction, which takes place twice a year and is typically the biggest sale for vintage time-pieces. Reardon is a leading authority on Patek Philippe watches, and the founder of Collectability, a website that trades exclusively in all things Patek.

There was one particular Patek timepiece in the auction that Reardon, who was bidding by phone, was particularly keen on: a very rare, pink gold perpetual calendar chronograph wristwatch, reference 1518, dating from 1948.

“The 1518 is the first perpetual calendar chronograph that Patek ever made, starting in 1942,” he tells me. “We’re all chasing the 281 examples ever made. This one happened to be in exceptional condition.” And did he land it? He laughs. “No chance. Normal market value I’d have said on a good day would be $1.3m to $1.4m. Then someone jumped the bid from $800,000 to $2m — in one bid.” It ended up selling for $3.6m (£2.9m).

Reardon was in the room at the Only Watch charity auction in Geneva in November 2019, when a Patek Philippe Grand Master Chime became the most expensive watch ever sold at auction, fetching £24.2m, eclipsing the £13.4m paid in 2014 for another Patek watch, the Henry Graves Supercomplication.

“It seemed impossible,” he remembers. “The bidding just kept going up and up. And there were gasps in the room, as they say, when the record was broken. I thought at the time that was the high point of the modern era. Although looking at what happened at Phillips this past June, maybe it wasn’t the high point with Patek Philippe at auction. Maybe it was just the beginning, and there is room for more growth and more fireworks.

“This was the first true live auction we have seen in months, and it was a frenzy. Less than 100 people in the room, socially distanced. But there were more than 3,000 phone and online bidders. That’s rather unprecedented for an auction,” he says.

“And watch after watch was just blowing away the estimates. For a pink 1518 to sell for £2.9m in this economic climate, it is a really interesting leading indicator of the high end of the market. People are putting their money in… I don’t want to call it an asset, but they are looking at watches as both a safe haven and a passionate investment.”

‘Only a Patek guy could say this, but Patek wins on all fronts — aesthetics, history, production’

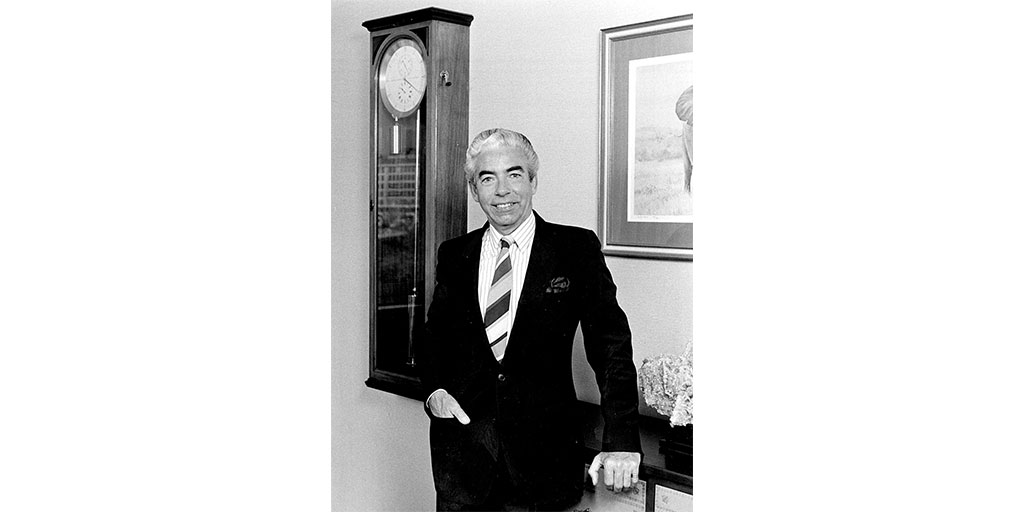

Which is very good news for Reardon. Having worked as an executive for Patek Philippe and in the auction world for both Sotheby’s and Christie’s, Reardon founded Collectability last December. The site not only trades in watches, clocks and Patek objets d’art, but also offers what Reardon calls “an education in Patek Philippe” through articles about specific references by the brand and the art of watch-making. Reardon had been in business with Collectability for barely three months before the Covid-19 pandemic arrived, laying waste to locked down economies around the world.

“I thought my business was over before it had begun,” he says. “Then after a few days, I started receiving some phone calls, from America, then the UK, Australia, Singapore and China. My company is recently born but we’ve hit the ground running and the growth has been much more than I expected. What’s happened in the watch world in relation to the pandemic is that people have the time, people want to connect, they want to learn, and they want to spend.”

The vintage and pre-owned watch market is estimated to be worth about $16bn (£12.2bn) annually. Reardon estimates the market in Pateks alone stands at around $1bn (£765m).

“Looking at eBay and Chrono 24 and other leading online sellers, it’s Rolex or Patek interchangeably as market leaders. In volume, it’s Rolex all day long,” he says, “but all of a sudden, the dollars creep up with Patek Philippe. The number of pieces in excess of $100,000 (£76,400) that are changing hands daily is extraordinary. This is the big surprise, in a world where we only hear negativity; that people want to buy watches. But they’re very particular in what they’re looking for. And what Collectability is all about is giving people the education and the resources to assist in buying the correct Patek Philippe for them at the right price.”

Reardon’s passion for watches began as a child, visiting the American Clock and Watch Museum in Bristol, Connecticut, close to where he grew up. He learned about clock repair as a hobby, never thinking he’d make a career in the world of watches. But after studying Humanities at college, in 1997 he became an intern at Sotheby’s in the watch department. It was at that point, he says, his “obsession” with Patek Philippe began.

“Once I started seeing these pieces and comparing and contrasting with other makers, there’s just no competition. Only a Patek guy could say this, but Patek wins on all fronts — aesthetically, historically, and in terms of their production methods.“Going back to the 19th century, the pieces they made were so creative, so aesthetically pleasing, mixing the art of enamelling and engraving, combined with the inside workings, which you don’t see, it’s the highest form of watchmaking. And that tradition continues to this day,” he says.

After three years at Sotheby’s, he worked as an executive for Patek, in sales training and distribution. In 2010, he moved back into the auction world, becoming the international head of watches at Christie’s in New York, overseeing about $100m a year in watch sales. He is also the author of Patek Philippe in America: Marketing the World’s Foremost Watch, published in 2008, and of two collectors’ guides.

‘People are now looking at watches as both a safe haven and a passionate investment’

The Patek company was founded in 1839 by Antoni Norbert Patek, a Polish nobleman, who had fought in the cavalry in the failed uprising against the Russian occupation of Poland in 1831, and been forced to flee into exile, firstly to France and then Geneva, Switzerland. There, he became interested in watchmaking and, in 1839, established his own company, purchasing movements from the numerous independent watchmakers working in the Valley de Joux around Geneva and mounting them in fine cases.

His first partner was another Polish émigré, the watchmaker Francois Czapek. The company employed half a dozen workers; and over the course of the first six years produced more than 1,000 watches, many embellished with enamel or fine engraving, bearing images of Polish heroes and Catholic saints, which held a particular appeal to the Polish émigré community.

But in 1845, the partnership with Czapek came to end, and Patek took on a new partner, a Parisian watch-maker Jean Adrien Philippe. Philippe had developed a stem-winding system, obviating the need for watch keys, which tended to damage the fine enamel settings on the watch casement and were frequently lost.

Other watch-makers had experimented with the stem-winding system, but Philippe’s development was particularly well-suited to the flat watches then coming into fashion. Philippe invested all his money in his new invention, but despite winning an award at the 1844 Exhibition of Products of French Industry, it was not a commercial success. However, he found one interested customer in Antoine Norbert de Patek (he’d assumed a French version of his name), who travelled to Paris to seek out Philippe and persuade him to become his partner.

The firm’s reputation was cemented in 1851 when it exhibited at the Great Exhibition of London, where Queen Victoria purchased a blue enamelled pendant watch for herself and a repeater for Prince Albert. British royal endorsement led to Patek becoming the watch of choice in every royal household in Europe — not least, in Russia. As Reardon points out, “in the 1850s and 1860s, Patek’s mortal enemies ended up being some of his best clients.”

Monsieur de Patek had tried to make inroads into the American market by visiting that country in 1843. “Everything went wrong that could do,” Reardon says. “As soon as he arrived in New York he was robbed of his watches; he complained about the price of cigars — ‘very expensive, five cents!’ He travelled the Mississippi River and his steamship became stuck on the sands and almost capsized. He wrote that he couldn’t wait for the day when clients had to go to him in Geneva.

It was royal patronage that would eventually open the door to the US market, with the ascendancy of a new generation of US plutocrats, industrialists and financiers. “They looked at European nobility as the ultimate benchmark, and everybody who had the money needed to buy a Patek Philippe. And Patek capitalised on that brilliantly,” says Reardon.

It was the American banker and railroad mogul Henry Graves who, in 1925, would commission the Patek watch that until last year held the record as the most expensive watch ever sold at auction: the Henry Graves Supercomplication. Complications — the functions on a watch additional to basic ones of timekeeping — would be an important factor in Patek consolidating its position at the summit of the watchmaking world.

In its early years, the company was renowned for the quality of its enamelling and engraving; it was not until the 1870s that complications became an added focus of its production, as rival watchmakers strived to outdo each other by adding ever more functions to their watches such as perpetual calendars, split-second chronographs, phases of the moon, and so on.

Henry Graves commissioned Patek Philippe to produce his Supercomplication pocket watch to outdo the Grande Complication watch of his friend and fellow ardent watch collector, the US automobile manufacturer James Packard, which contained a mere 10 complications. The Supercomplication, which took three years to design and a further five to make, contained no fewer than 24 complications including timings of sunset and sunrise, petite and grande sonnerie chimes, and a celestial map of New York as seen from Graves’ apartment on Fifth Avenue.

The mystique of Patek has been carefully maintained over the years, not least in more recent times through its advertising slogan, “You never actually own a Patek Philippe, You merely look after it for the next generation”, accompanying photographs of affluent and beautifully tailored fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, and grandparents and grandchildren, which has been employed since 1996, and which posits a Patek timepiece as something akin to a protected heritage monument.

‘Many buyers just want to have something they can connect to emotionally that is very high quality and that has true rarity — with vintage Patek it’s real’

The company does not reveal its precise annual production total, but estimates put it at between 60,000 and 70,000 pieces. In comparison Rolex, which is similarly secretive, is thought to produce around one million watches per year. “When I was working at Patek, we used to joke that in Patek’s entire history they’ve made fewer watches than Rolex make in one year,” Reardon says. “Today, it’s untrue. But 20 years ago, you could say it was true.”

Patek Philippe produces more than 100 different models of clocks, pocket watches, special pieces, as well as the various men’s and women’s wristwatches. No single model is made in great quantities, which keeps demand at a perpetually feverish level. The Nautilus 5711/1A, for example, which has been described as the world’s most desirable steel sports wristwatch, is, theoretically currently in production, but virtually impossible to find through an authorised Patek dealer.

“It’s become something of an obsession over the past couple of years,” Reardon says. “But it’s very scary when you have a watch that you can buy for the company’s suggested retail price of $30,000 — if you can find one — and an hour later sell it for $60,000. That creates a huge headache for retailers in deciding who gets what, because you’re literally just giving people money when they buy a watch.

“I have heard stories of some shops doing unsavoury things such as selling the watch on paper and then reselling it at secondary market value. That could result in closure if you’re a retailer.” Reardon adds he tries to stay out of what he calls “the Nautilus game”.

“I find it very bubbly. I’ve bought and sold a couple but it’s not what I do. But there’s plenty of dealers who this is what they do; they flip Nautiluses. It’s a world where people can make money — and also lose money very quickly,” he says. “What I’m trying to do with Collectability is identify the right ingredient of pieces I think could be the next big thing and my focus is primarily vintage.”

So what would he recommend for the seasoned watch collector, or the novice dipping their toe tentatively into the market for a vintage Patek? During the lockdown period, he says, he saw a particular uptake among his clientele in clocks and pocket watches. “I’ve been predicting an uptick in the Patek pocket watch market for years, and now it’s finally happening,” he laughs. “It took a pandemic for it to happen, but with people in their twenties and thirties, pocket watches seem to have caught on. A 25-year-old client recently bought a pocket watch for $7,000 and he just thought it was cool — as simple as that.”

Until 1910, Patek made only pocket watches, and it was another 20 years before wristwatches became really dominant. Over more than 90 years, the company produced between 1,000 and 5,000 pocket watches per year. “And there are a lot still out there,” Reardon says. (Patek continues to make them but on a very limited basis, accounting for less than one per cent of the manufacture’s overall production.)

“It’s easier to find a great-condition pocket watch from the 1890s than it is to find a great condition Patek wristwatch from the 1940s to the 1960s. Wristwatches were worn, exposed to different environments, whether it’s sun or moisture, so they deteriorate more quickly if they’re used. Pocket watches were often just left in boxes,” he says. “You can pay $3,000 to $4,000 for a pocket watch, and when and if you want to sell it, the odds are you’ll get your money back or better.”

For a collectable wristwatch, Reardon would recommend the reference 3445. “It is a classic round, automatic Calatrava, manufactured from the 1960s through to the 1980s, that you can buy for $10,000 to $12,000. Or you could buy a reference 96 in yellow gold for $6,000 to $8,000. They’re quite small, but we’re seeing a trend towards smaller watches.”

A more unusual choice, he says, would be a skeleton watch. Patek first started making skeletons in the 1860s, producing a small series of pocket watches, often made specifically for exhibitions and display purposes, to showcase the craftsmanship involved in the inner workings of a Patek Philippe timepiece. Production stopped in the late 19th century. But the skeleton pocket watches were revived in limited numbers in the late 1970s, along with skeletonised wristwatches.

In May 2019, a ref 912 skeleton pocket watch, made of 18k yellow gold and set with pearls, rubies and diamonds was sold at auction for $825,000 (£630,000). That watch — and price — was exceptional.

“Generally speaking, they are very reasonably priced,” Reardon says. “You can spend $60,000 for a Nautilus, but for half the price you can have something with much more workmanship, far fewer in terms of production numbers; something that is a real work of art rather than a regular production piece.”

Reardon’s operation is relatively modest, with just one other colleague, Tania Edwards, who for 10 years was marketing director for the Henri Stern Agency (Patek Philippe USA) and for 23 years has been editor of the Patek Philippe magazine. Typically, Collectability has between 50 and 100 pieces in its inventory, mostly sourced from contacts he has built up in his more than 25 years in the world of vintage watches.

‘You can’t buy a Van Gogh for $5,000, but you can buy an absolutely incredible Patek pocket watch’

“These are collectors looking to trade or upgrade, and then some families that are willing to sell their heirlooms. And there are pieces I know have been sitting in collections for years that I’ve been chasing,” he says. “I’m very focussed on quality, and on buying from private individuals rather than other dealers.

“I try to have things at different price points, so people can buy something for under $5,000, or under $10,000. Many of my customers — at a lower price point typically — they’re thinking the same thing: it’s something they can enjoy, something they can wear, and down the road if they can actually make their money back, that’s a pleasure he says. “But many buyers just want to have something they can connect to emotionally, that is very high quality and that has true rarity. We hear these catchphrases all the time, but in the world of vintage Patek it’s real.”

For Reardon, the question of whether a vintage Patek is a better investment than, say, a painting or a sculpture, is moot. There are collectors, he says, who put their watches straight in a vault: “We call those watches ‘safe queens’. They’re just commodity trading. And I don’t find that very interesting. For me, watches are a much more concrete form of art, mechanics, history, aesthetics and even fashion, than you can find in a painting. But that’s because this is my obsession.

“I could have a wonderful debate about why a Patek 1518 is much more interesting than a Picasso — but there’s no right answer to that. The value is in the eye of the beholder. But in my opinion, the micro-mechanical works of art that are Patek pieces is fantastic, and they’re across all price points.”

He laughs. “You can’t buy a Van Gogh for $5,000, but you can buy an absolutely incredible Patek pocket watch.”

Reardon himself wears a Patek Philippe Aquanaut. His own collection, he says, is “humble and small, but each piece has a story to tell, an emotional connection”.

Oh, and he has three children — so really, he’s merely looking after them….

To order a copy of Esquire The Big Watch Book 2020, please go to this link.