Dr. Peter Friess, director and curator to the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva, has been very busy in recent years helping build the Patek Philippe Museum’s collection and raising awareness of what is globally regarded as one the greatest horological museums in the world. In this candid and revealing interview, Dr. Friess discusses with John Reardon what he has been doing the last few weeks and months during the pandemic, what has been done to deliver a superlative visitor experience, and some hints on the future of the Patek Philippe Museum. This interview brings insight into what it is like to be the curator of the Patek Philippe museum and how the museum is boldly evolving into a 21st century horological center of interdisciplinary studies.

JR: How have you fared through the quarantine?

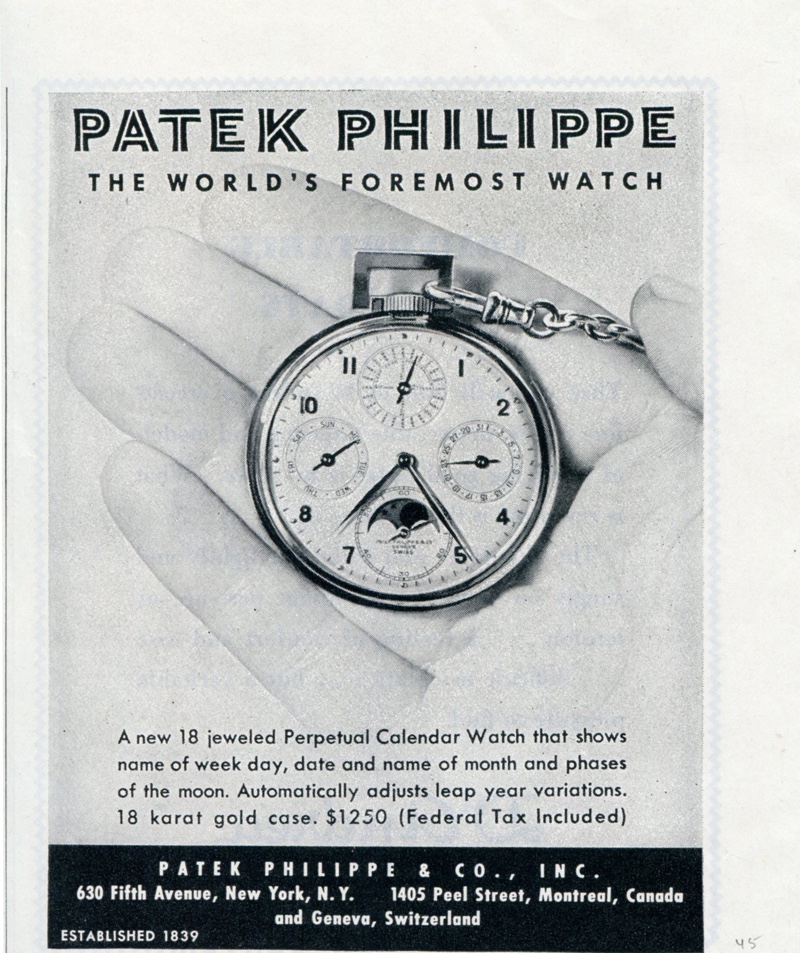

PFR: It is sad to see no visitors at all coming to this wonderful place. It seems that time stands still, in more ways than one. We have had very strong attendance, growing year over year, since the opening of the Patek Philippe Museum almost 20 years ago. I’m afraid it will take quite some time for people to be able to travel and visit us again.

In terms of their ability to do their work, the research team for the exhibit on the other hand, was able to continue with little interruption after the first couple weeks of the pandemic. Most of us are now working from home. We are connected electronically and, since most of our materials, including databases, are digitally available, every one of us was able to keep moving forward. There are of course disadvantages to not having daily face-to-face interaction, but one definite advantage is the time saved on commuting. And, we’re helping to keep the streets empty and safer. It is a bit of a challenge to create a team spirit that way, but I already feel that our work style may be permanently changed and that some staff members may not regularly return to their desks in the museum but continue to work from home.

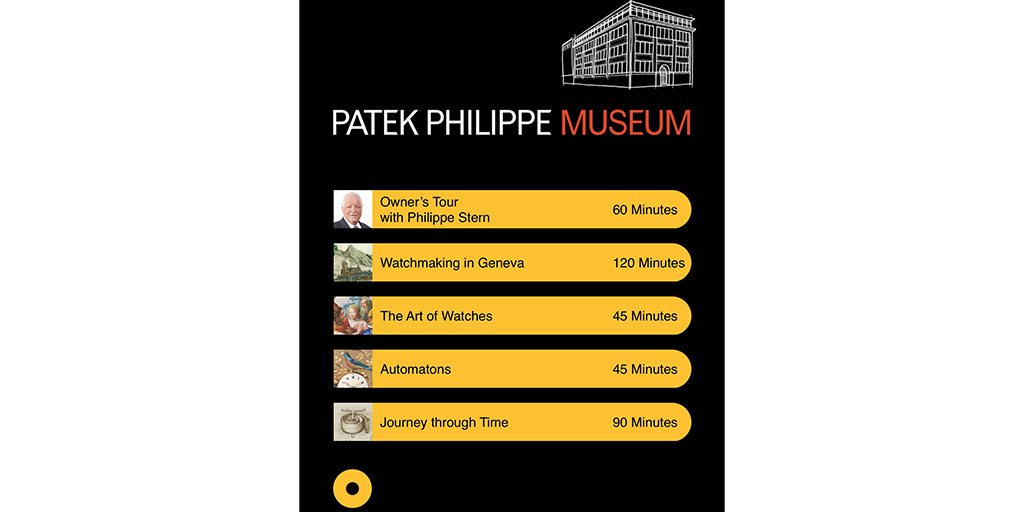

JR: You have literally led the museum into the 21st century by creating a digital/live experience for visitors to the museum. Can you tell us about the new iPads and your vision for the most pleasant and informative visit to the museum?

PFR: The modern technology of the iPad allows us to do amazing things. First, from the curatorial standpoint, it’s very easy to develop and revise technical and historical information, almost in real time. We have created a workflow where every piece of information added to the system instantly reaches, in one way or another, our visitors on site or online. Whatever we produce, a booklet, a catalogue, a movie, a brochure, a label, an article, the source of information is just one database. And, as mentioned, with a digital device the team can work together from anywhere in Geneva, on the Moon or on Mars. I still prefer to work on earth from my beautiful office in Geneva.

For our visitors, this technology provides a wealth of information and varieties of access that printed labels can never provide. Visitors can also choose different tracks through the exhibition, each with its own curatorial information. The real advantage is the ability to include visuals, still images as well as animations. If they want for instance, visitors can take a virtual trip into the movement to see the mechanics — “inside information,” as it were, previously available only to skilled watchmakers. We are getting better and better every day at developing these experiences.

JR: Will this digital experience ever be available to those that cannot visit this museum now or in the future?

PFR: Let me first point out that in the last two years, we have created at least one story for each showcase, providing a total of 154 stories for the collection of historical watches and 143 stories for the Patek Philippe collection. This amounts to more than twenty hours of audio content, explaining the history of watchmaking and the many facets of Patek Philippe’s history since 1839 up to the present. Everything is available in English, French and German. More languages will follow soon.

Very little of this incredible content, including details from our archives, has reached the public before. It provides answers to almost every question you might have about Patek Philippe and the history of timekeeping. This digital information is transferrable from the iPad to other platforms. Of course, we are now discussing ways to also provide this information in the future via the internet to people who cannot visit the museum in person—but we are not there yet.

JR: Will any changes be noticeable for visitors when they next visit the museum? Does the Patek Philippe Museum still actively buy watches? You are the ultimate horological treasure-hunter, can you share a story or two of pieces you found and how they ended up at the museum?

PFR: In March, the museum acquired a collection of 40 very rare watches with enamel paintings made between 1625 and 1660. They arrived two days before we all got locked down in our countries, cities and homes. The collection represents the largest and most important single acquisition the museum has ever made. These pieces came from a private collector, and we were lucky that the owner was willing to sell all his pieces at once. He wanted to make sure they stayed together so that he can still visit them at any time. We offered him a free museum ticket for the rest of his life.

Within our collection, these watches fill some major gaps in the early period of watchmaking. We can proudly state that our collection of pocket watches with enamel paintings is unique and absolutely comparable with the collections of such large museums as the Musée du Louvre in Paris, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, or the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Most of the watches in this collection were made in the city of Blois, France where the technique of enamel painting originated around 1620. The French silversmith Jean Toutin (1578 -1641) developed and perfected this technique in his own workshop. He mixed pigments made of metal oxides with lavender oil; the mixture was then applied with a brush to a metal surface, usually gold, covered with a white layer of enamel. Firing them in an oven gave the colors their special glow.

JR: Why is enamel painting so important for your museum?

PFR: Patek Philippe has always been deeply devoted to enamel painting as a craft. In the 20th century, the presidents of Patek Philippe, Henri Stern, who died in 2002, and his son Philippe Stern, both passionate about enameled watches, saved that now-rare craft from extinction. After the Geneva University of Applied Arts closed its enamel painting department in the 1970s, it was Patek Philippe that gave such supremely talented artists as Carlo Poluzzi and his last student Suzanne Rohr the opportunities they needed to pursue their profession.

Under current president Thierry Stern, the company continues its support of this endangered tradition: Patek Philippe employs its own painters in addition to many practitioners of other rare crafts. These highly skilled workers often come to our museum to be inspired by the early enamel paintings on display, some going back 400 years. So, you see that watches acquired for our collection form a bridge from the past to the future.

JR: The museum also offers guided tours to the public at select times given by professional tour guides. Did you originally write their tour script and how are the tour guides trained to literally be the gatekeepers to Patek Philippe’s history?

PFR: Of course, having a personal guide is the best option you can have visiting the Patek Philippe Museum. You can ask questions and get answers firsthand. The museum has a fantastic group of enthusiastic, well-trained tour guides—yes, we do prepare scripts for them—providing knowledge of the collections to visitors from around the world. We give tours in many languages. Some of our guides have been working for the museum since its opening in 2001. They know the collections by heart and are extremely passionate about the subject.

The audio tours complement what the guides do, especially for those who want to explore the collection on their own. The tour guides themselves enjoy the content of the audio-guide and are eagerly using the iPad to learn more about the subject and improve their tours. If they need help fielding some visitor questions, they never hesitate to contact the team, and we enjoy getting such questions, because we often learn from our visitors.

JR: Please share with us some of your favorite stories of people you have interacted with when they visit the museum. I imagine you have met some incredible people with equally incredible stories!

PFR: Serendipity frequently enters the game. Recently I was contacted by someone on LinkedIn. I assumed he wanted me to give him a private tour of the museum. I told him this was something I couldn’t promise— until he told me that I had completely misunderstood his request. He said his private plane was waiting for me at the airport, whenever I’m ready. Once we landed an hour later, he took me for coffee and then to his house, showing me his amazing collection of 18th-century watches, with hundreds of pieces that have not been seen for at least 50 years.

Many owners of Patek Philippe watches I have encountered, whether owners of a single beloved piece or a collection, want to learn everything they can about them and the history of the company. After finding more about the marvelous little machine on their wrist, they leave the museum even prouder than when they entered.

JR: Do people bring their vintage Patek to the museum in hopes of learning more about their watches?

PFR: That is one of the most frequent requests we have. People constantly email, phone, or visit us with questions about their watches. This contact benefits both sides. We sometimes see rare pieces which we can add to our knowledge data base, perhaps even gingerly inquiring of the owner about adding the piece to our collections (paying of course for it, but I hope not too much). Collectors in turn learn about the history of their watch and where it figures into company history. From a personal standpoint, I am often rewarded with a new friend who shares my interests.

JR: Was there ever a watch that you wanted but couldn’t acquire for some reason?

PFR: Sometimes there are collectors in the auction room who are willing to pay more for a watch than we want to spend. I often feel sad on such occasions, but I know that watches in private collections almost all resurface on the market, changing hands again and again over the years. It is actually fun to see how some watches move from one collection to another—and maybe even back again. There is always a good chance that a piece we did not get this time will still end up in the museum one day. But I have to admit that if there is a watch that absolutely must be in the museum, we always manage to figure out a way to get it.

I personally remember being in a bidding war for an English pocket watch at a London auction. Normally, a watch like the one we wanted is not that pricey. But my competitor was apparently desperate for it and the bidding soon skyrocketed to seven digits. We finally dropped out, and the beautiful timekeeper remained in England, where it was originally made for one of the Kings of England. Okay, not a bad outcome, but probably a bit surprising to the winner who kept bidding up the price, probably feeling that we would never stop raising the bar. At the end he suddenly realized that he now had to pay the bill. He rushed out of the auction room, his face suddenly drained of color.

I could have given you dozens of other stories, because the auction room is always full of dreams, grandiose hopes, and big egos.

JR: Are there any holy grails that the Patek Philippe Museum still wants to find? What are the three watches or clocks you would like to see at the museum that are presently not there?

PFR: Nice try with this question! I do have a lot of secret desires in that regard, which are only satisfied after we have successfully acquired the piece. Sometimes the hunt for certain rare pieces can go on for several years. But, compared to eternity, that is a very short time to wait.

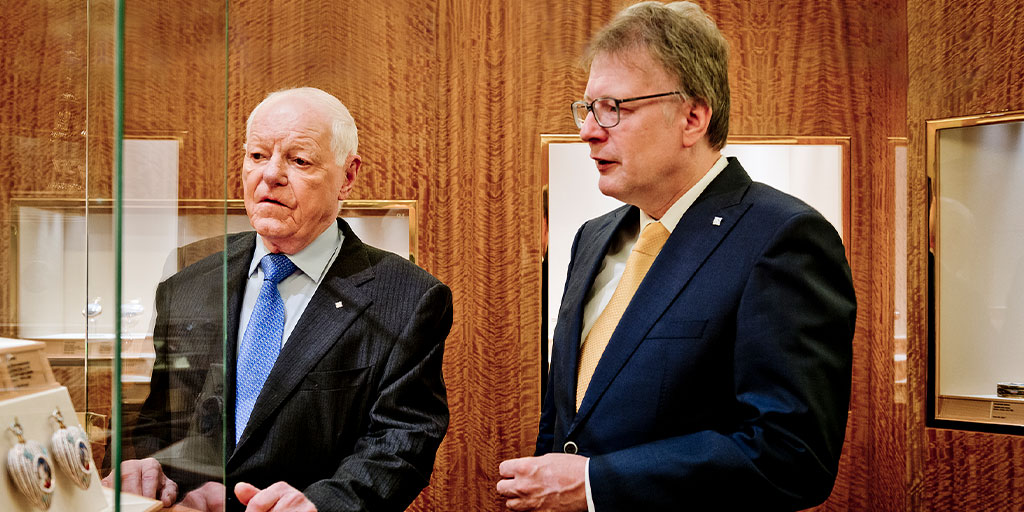

JR: You have the honor of working closely with Mr. Philippe Stern in building the Patek Philippe Museum and its message. What is the vision of the museum and what is your role in building on this vision?

PFR: We have two core messages:

- The invention of timekeepers is a great European story, going back almost one thousand years, with Geneva playing a central role.

- For almost 200 years, Patek Philippe has been a leader in creating precise and elegant watches.

And, what can I say about Philippe Stern? He is iconic in the world of those who worship the mechanical watch and for the men and women who make them. But, most important from my standpoint, he is a born museum man. This is the man who saved the company during the quartz crisis and took it to new heights by doubling down on heritage. I have already mentioned what he did to preserve the nearly lost profession of enamel painting. The museum is just an extension of that sense of horological heritage. In fact, if the World Heritage Fund had a category for companies protecting endangered crafts, Patek Philippe would be a top candidate, with special recognition for Mr. Stern.

Needless to say, he is immensely supportive of the museum. He loves the collections, most of which he was responsible for acquiring (a collecting passion starting in his childhood, by the way.) Today, top-tier watch collecting is a high stakes game, and you have to be fast and decisive to seize the moment. Mr. Stern epitomizes that quality. Case-in- point: the recent acquisition of the rare enameled watches that I described. He made the decision to go for it very quickly, with little hesitation, and stuck by it.

I feel very fortunate that these same qualities are shown in his son, current president Thierry Stern, who also stands strongly behind the museum. He is a manager’s manager, but above all he knows the watchmaking business inside and out. As we point out in the audio-tour, he has a special appreciation for the sounds made by watches, to the extent that he insists on passing off on the sounds emitted by each watch they produce. One could say he has a “golden ear.” This is important for the museum, because these sounds are an important feature of the heritage of mechanical watches, which he greatly appreciates. I can see the delight in his eyes as he listens to sounds of our minute repeaters and grand complications.

JR: Can you comment on the first curator of the Patek Philippe Museum, Mr. Alan Banbery? Do you speak to him personally or professionally?

PFR: Without Alan Banbery there would probably be no Patek Philippe Museum. He got it all started some thirty years ago, slowly but with a vision, and not least, the ability to convince Henri and Philippe Stern. Together the two presidents understood that such a museum would not only explain the history of the company and of timekeeping to the public but would help serve to unify the entire staff of Patek Philippe around a shared vision.

Alan and I meet regularly over lunch. For me, he is a vital connection to the history of the museum. We have developed a collegial relationship and a friendship built on mutual respect. I have had my share of successes in directing the museum, and I know it’s because I am standing on his shoulders.

JR: What is your average workday like for you?

PFR: Continuing to build this still young museum is demanding, time- consuming and immensely rewarding. Fortunately, I have a great team around me, as well as a group of wise colleagues from around the world — people who have themselves built museums and know how to develop audiences. I rely on them daily in my efforts to take the museum to the next level. I am constantly seeking new ways to reach both the general public and specialists to spread the word about our museum. Planning for and attending auctions is naturally a big part of any workday. They happen all the time and all over the world. You need a “world timer watch” to manage yourself in 24 time zones. And as the museum has grown so has the volume of emails, as you can well imagine. Every day brings something new and surprising. I find all of this very energizing.

JR: When you are at the museum alone and it is closed, what is it like walking through the empty exhibition floors? Do you think of what it is like visiting the museum for the first time? What have you changed in terms of a visitors’ flow through the museum?

PFR: This is a great question. It is almost a haunting experience to be completely alone in a room with 3,000 of some of the most historic watches ever made. It is hard for me to put the feeling into words, even though I have written many thousands of words about them. I always have a sensation of seeing these treasures for the first time. How could you ever be jaded when you see the pocket watch the Queen of England bought for herself; the Patek Philippe chronometers that set the standards in precision timekeeping; the very first wristwatch with a perpetual calendar — a veritable miracle of craftsmanship; the early world timer watches? And displayed just a few centimeters apart from each other are four of the world’s most complicated timepieces: Caliber 89, Star Caliber 2000, the Grand Master Chime, and the 1929 Packard (not the automobile!), mythical names all. I can tell you it is a great way to start and end the workday.

Previously the watches were exhibited in chronological order. We have totally restructured the presentation, so that all of our pieces are now grouped under various themes. This allows us to provide context, technical and historical, and to tell our visitors stories about them. Visitors can still home in on the particular watches and watch types that most interest them, and we found they enjoy hearing stories about the role of kings and queens, the French Revolution, or the Industrial Revolution, etc. in the history of watchmaking. Thematic groupings include one for perpetual calendars in pocket and wristwatches, and others specifically for chronometers, world timers, chronographs, repeaters, grand complications, enamel paintings, etc. Visitors, auctioneers, collectors, and my colleagues at Patek Philippe have reacted enthusiastically to this reorganization.

JR: Reading through the rave reviews of the Patek Philippe Museum on TripAdvisor, many people have asked why they cannot take photographs within the museum. Can you comment on this to set the record straight?

PFR: There are several reasons for this restriction. First of all, our security specialists have given us strict guidelines for protecting our treasures from harm. Furthermore, visitors themselves tell us they don’t appreciate other visitors taking pictures, particularly the selfies that obstruct viewing and otherwise disturb the museum experience. I certainly understand the temptation to take home your personal photos of favorite objects. My suggestion is to just pick up one of our iPads, which contain brilliant studio-quality photographs of each and every object. Taken from several angles, our photos allow you to see behind and even inside the displayed objects.

JR: Speaking of records, you have held in your hands almost all the record breaking pieces of the modern era. What watches come to mind as the most awe inspiring?

PFR: Well it depends on what you mean by the “modern era.” Please permit me some chronological latitude here, because this allows me to mention a recent acquisition that is indeed awe inspiring: the enamel – painted watch with hundreds of diamonds made around 1650 by Jehan Cremsdorff, a Parisian watchmaker. Its diamonds reflect the light like a display of fireworks. The competition for it went into the millions of Euros — a record for pocket watches, at least for the moment.

And of course, there is the world price record with the Breguet Sympathique, made for the Duc d’Orléans. The museum owns two Sympathiques and they are positioned right next to each other. Once a week, our watchmakers carefully wind them, among the timekeepers we keep in running condition.

And then there is the beautiful reference 1527 from 1940 we acquired from Christie’s. A wristwatch with a caliber 13-130, it has a chronograph, a 30-minute recorder, a perpetual calendar, date of the month, day of the week, month of the year and phases of the moon. A record-breaker in its day.

These famous timekeepers have been known to collectors for a long time. Over the years, they have wandered over various private collections, finally finding a good home in the Patek Philippe Museum.

JR: The Patek Philippe Museum has notably been giving special tours to children over the years. What kinds of questions do children ask when they visit the museum?

PFR: I’m proud that we make a real effort to reach children. For a specialty museum like ours, this does present a special challenge to make the displays interesting for them. But we should never underestimate the curiosity and imaginations of kids. Indulge me with a personal example. My seven-year old son Miles asked me to give one of his friends a private tour. I was flattered to be asked and of course said yes. So, on a Saturday morning, I started the tour but after five minutes Miles got bored with my talk. He quickly took over. “Listen,” he said to his friend as he pointed to one of the show cases, “This is the watch of Mr. Samuel Pepys (whom he had just learned about in school), the man who observed firsthand the Great Fire of London in 1666. He was so frightened that he buried this watch in a hole, and later went back to pick it up after the nightmare was over. And, look, it is still working!” Miles said, pointing to our stunning over-sized Caliber 89. OK, no matter that the museum has nothing associated with the famous English diarist and the watch was made three hundred years after the fire. What did matter is that Miles showed me that kids have wonderful imaginations and make up their own stories. That is the kind of imagination we want to spark when we take children on our special tours.

JR: I am amazed how many top collectors have asked me what I think of the Patek Philippe Museum ‘gift shop’ that one visits upon arriving and leaving the building. I personally buy a handful of Patek Philippe pens every time I visit! Anything that says Patek on it seems to have a magic to it. What is your take on how people perceive the brand of Patek Philippe, itself an almost cult-like obsession to own a ‘piece’ of the history?

PFR: The name Patek does seem to have that magic, which is wonderful news for our brand. You are far from alone in wanting to take home something from the gift shop that reminds you of your visit. This is one of the roles of museum gift shops, and I’m glad to hear what the collectors are telling you. But I want visitors to know that we also sell large numbers of authoritative books about the history of the company and of watches, including catalogues of the collections, which are prized by collectors.

JR: Your favorite non-Patek at the museum?

PFR: My current favorite is an astronomical watch made in 1778 by the London watchmaker George Margetts. It dominates its showcase, where one can see up close the dial with its many hands, the perfectly designed movement with just enough wheels for its many complications, and the enamel painted case. It is signed by the watchmaker, and shows the number 1, which it is in many senses.

JR: Your favorite Patek at the museum?

PFR: The pocket chronometer with reference 810. It was built in 1930. It is equipped with a counterpoised lateral lever escapement and a tourbillon made by Hector Golay. In its rotating cage, a Guillaume balance oscillates with a specially optimized hairspring to ensure the constant frequency of the balance. It was fine-tuned by master adjuster François Modoux in 1933 and again in 1962 by Max Studer, both Patek Philippe super stars. Between 1943 and 1963, groomed and pampered like a prize racehorse, the watch was entered nine times in the Geneva Observatory contests and won every time. The pocket chronometer represents the summit of Patek Philippe expertise in the high-stakes timing tests given at the Geneva Observatory.

JR: And, I must ask, what watch are you now wearing?

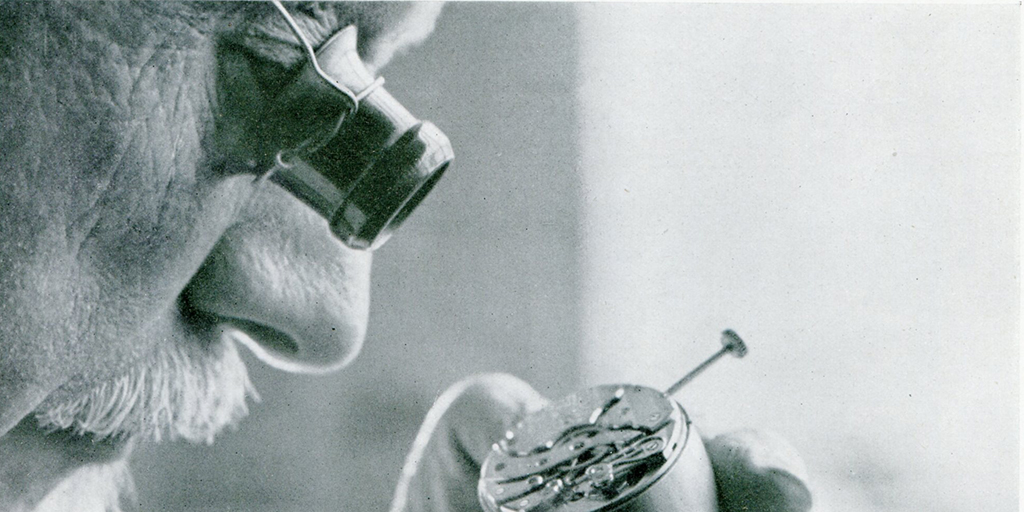

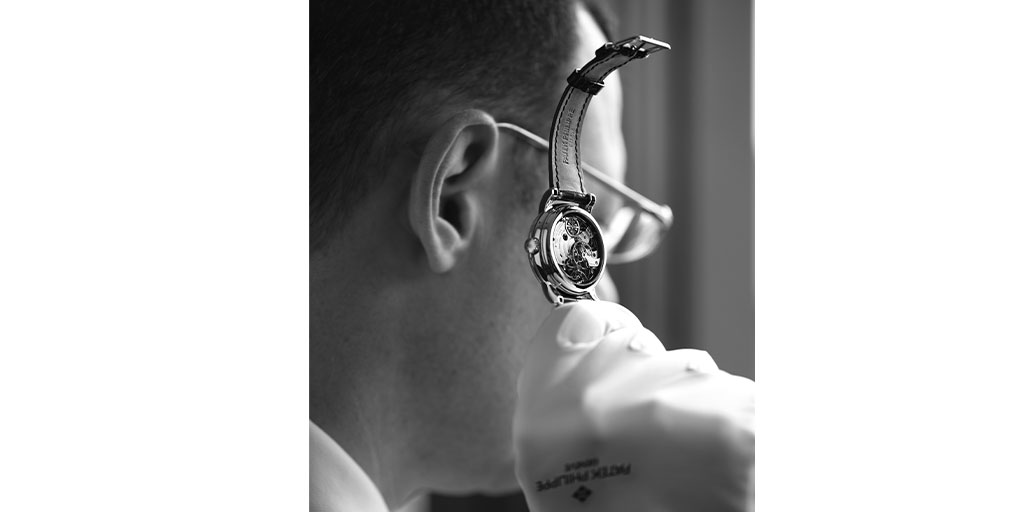

PFR: I have to admit I am not wearing a watch at all, and rarely do. Don’t ask me why—maybe because I love watches too much. Sometimes I open a showcase and hold a famous piece in my hands. Being a master watchmaker myself, I will often then take the piece to the workshop and have a look inside. Happily, I am given the privilege of taking them apart (so long as I agree to put them back together.) I can’t tell you what a joy this is.

JR: What is your most important project that you are working on right now?

PFR: At the top of my to-do list is the production of two small volumes about both the Antique Collection and the Patek Philippe Collection, each about 100 pages, designed to introduce the museum to a wide audience. This project is already well along. We are also redoing the catalogue of the Antique Collection, since it has sold out and we have acquired many more pieces after the first edition was published. At the same time, we are planning to produce a completely new catalogue of the Patek Philippe collection. In my dreams, I see three volumes with a special index designed for quick access to all the watches and with more information from our archives. This should be especially useful to collectors of our watches, giving them all the information they need to understand the pieces they own or are seeking. I am happy to get ideas from the collecting community about what else they might need from this volume. Just shoot me an email.

JR: Thank you so much for your time!

Special and sincere thanks to Dr. Friess for his time answering these questions and speaking directly to the Patek Philippe collecting community. Dr. Friess welcomes your questions and ideas regarding the Patek Philippe Museum and in particular on ideas of how the Patek collecting community can more directly engage with the museum. Dr. Friess can be reached at [email protected].