My desire to visit The Patek Philippe Museum began in May of 2015 after watching coverage of the twelve-day event: “Patek Philippe Watch Art Grand Exhibition London”. Just two years later, I would observe online as so many incredible timepieces traveled across the world again for “The Art of Watches Grand Exhibition New York”. I was left feeling as if I had missed two opportunities of a lifetime by not flying north from Florida to attend the events. When the publicity of what appeared to be the best exhibition in Singapore of 2019 took place, I made a promise to myself that I would travel to Switzerland in 2020 to witness the museum in person. However, within the first quarter of 2020, the world came to an abrupt halt with the COVID-19 pandemic. I am incredibly fortunate that neither I, nor my loved ones, were affected by the disease. I was also blessed to have had an incredible support system by way of family, job security, and a community of passionate watch enthusiasts that invigorated my passion and education while being secluded. In what felt like a perpetual rate of output, Collectability provided comprehensive articles, in-depth YouTube videos, and began an unrivaled podcast that provided as much Patek Philippe content as I could possibly ask for.

Through personal correspondence, I received encouragement and support on watch subjects I was feverishly researching. I thrived in isolation by making friends with like-minded individuals on social media, enjoying online resources, and the newly acquired books on Patek Philippe which I had spent years hunting down. While my plans to visit the museum were sidelined for over a year and a half, I will always look back at this period with great joy in that it elevated my passion for Patek Philippe. While I’m only able to highlight a fraction of the timepieces from my weekend in Geneva, I hope that this article paints a picture for those who have not yet been fortunate to visit the museum in person. And hopefully, my experience will inspire others who eagerly await their horological pilgrimage to The Patek Philippe Museum.

I arrived in Geneva and immediately went to the museum. Upon entering the lobby, I was astounded by who I would see first — none other than Peter Friess, the museum director who personally guided a few visitors into the lobby to demonstrate an automaton of singing birds. The mechanical creatures whistled and rotated on the edges of a floral arrangement on top of a fountain clock. It was as if by fate this incomparable first impression occurred. We were then greeted by our tour guide, Ute Blechschmidt, and proceeded into the next room. As I slid my key card and was granted access through the automatic sliding doors, a wave of euphoria would come over me as I had finally arrived.

First stop was the library. Perhaps less extravagant than the rest of the museum, the library very much spoke to my heart. Located within its own section on the top floor, it is home to thousands of horological publications. A range of basic reads to gigantic tomes dedicated to the most decorated watch collections surrounded the perimeter of the library. Positioned in the corners of the room were astronomical timepieces, while in the center section was displays of incredibly ornate examples of enamels predating the manufacturer. It was an incredible addition to the museum, and while I would have loved to wander looking for books to search for in the future, my avidity summoned me towards the timepieces on the floors below.

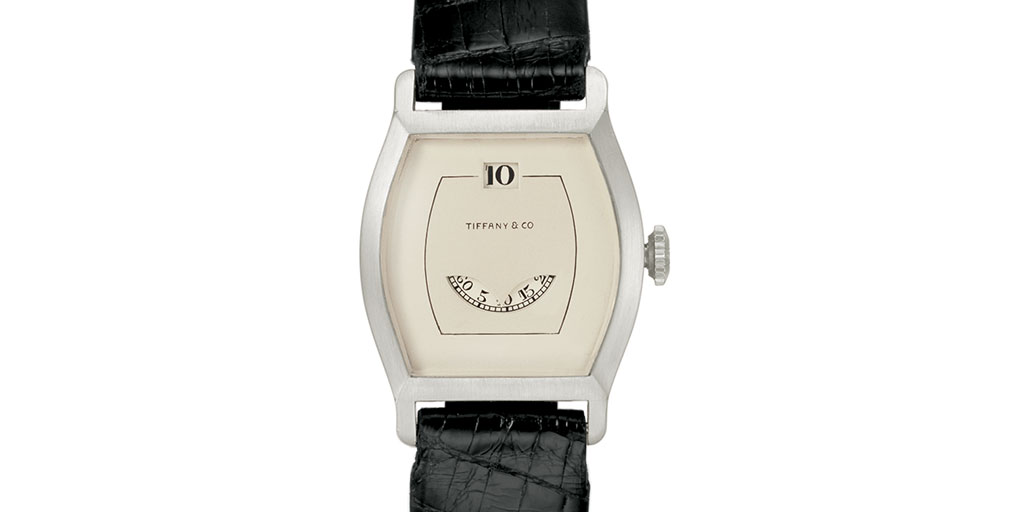

One particular standout from the museum is a genre of wristwatches — jump hours — that coincidentally were covered in my first article for Collectability. After walking past the Calibre 89, a tiny wristwatch discreetly positioned in the corner of the second floor caught my attention: one of the first jump hour wristwatches which can be seen above. With sixty-one years of seniority over its siblings (the ref. 3969P and ref. 3969R), I felt a sense of relief that it had not been among the timepieces being worked on by the watchmakers on the first floor. I was delighted that its display case was not aligned against a wall, because when I peeked my head to admire the profile of the watch, I caught glimpse of a detail I hadn’t discovered in my initial investigation. On the case back was an engraving of the past owner’s initials! The letters “E.K.” were still distinguishable.

As mentioned in my article on jump hours, a case back engraving is also on the rectangular tortue shaped jump hour. This timepiece, formerly belonging to T.H. Gillespie was displayed in the opposite corner of the same floor, right beside the digital Tiffany & Co. wristwatch (above). Seeing these three wristwatches within one day brought a special feeling to me. It was as if my watch pilgrimage to the Patek Philippe Museum had been completed within 30 minutes of arrival. Yet the day was still young and there would be so much more cover.

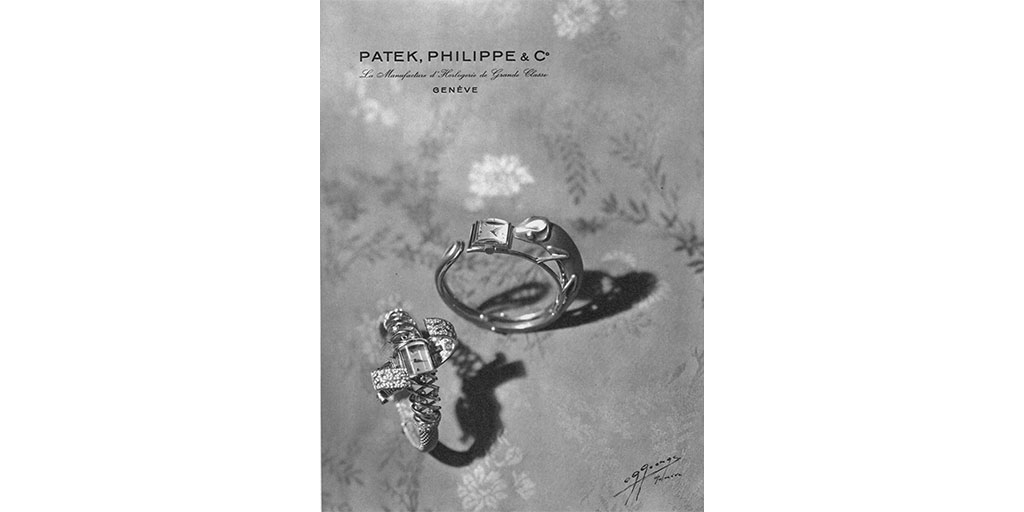

When it comes to the design focused timepieces, I would venture to say Patek Philippe was making some of the most avant-garde examples of all brands throughout the mid-20th century. This is particularly emphasized when it comes to the ladies’ references. I came to realize this while admiring examples within John Reardon’s book, ‘Patek Philippe in America Reference Guide Volume 2 Ladies’ Watches’. While most of these diminutive wristwatches are quite difficult to read, and remain to be fully appreciated by the collectors, I often find myself awestruck while looking at them in advertisements or in old auction catalogues. Of course, one is more likely to cross paths with a woman wearing the likes of a Twenty-4, a Nautilus, or my favorite modern chronograph by the brand, the ref. 7150/250R-001. Although, if I were to see someone wearing any of the daring designs from this golden era of watchmaking, I’d immediately feel compelled to speak to them about their interest in watches.

A model that exudes this the most is the ref. 1252. The timepiece is a bangle style bracelet made in the form of a chameleon. At the mid-section of the 18K yellow gold bracelet, the timepiece folds open, allowing the reptile’s tail to conform to the wrist. On any other occasion, having a creature with such beady eyes attached to one’s forearm would result in shrieks of terror. However, in this case one could expect onlookers’ jaws to drop in approbation.

This breathtaking wristwatch dates to 1947, featuring a round 8 ligne movement. The bracelet is 68.7 mm in diameter, featuring applied Arabic numerals at 6 and twelve, in addition to triangular indexes. One can assume this was a collaboration with a jeweler, as it likely required a different skill set offered from the case makers which typically worked with Patek Philippe. While I was informed on the tour by Mrs. Blechschmidt that the imaginative timepiece was not a piece-unique of the era, I could only infer that the ref. 1252 was made in very low quantities. Beyond this specific piece within the collection, I have only encountered one model which was featured within a 1952 advertisement signed by the photographer E.G. George. Within several outstanding ads from this era, one can notice this signature at the bottom right corner.

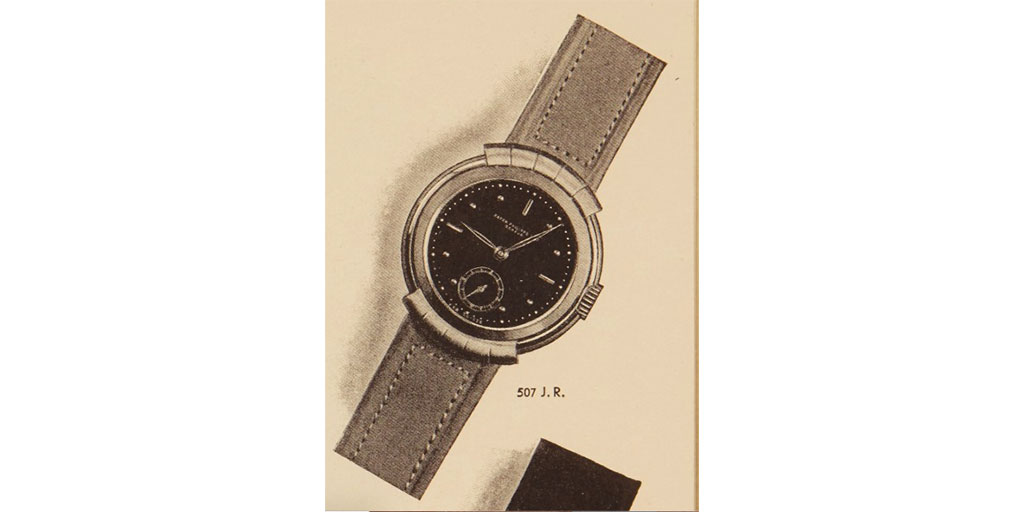

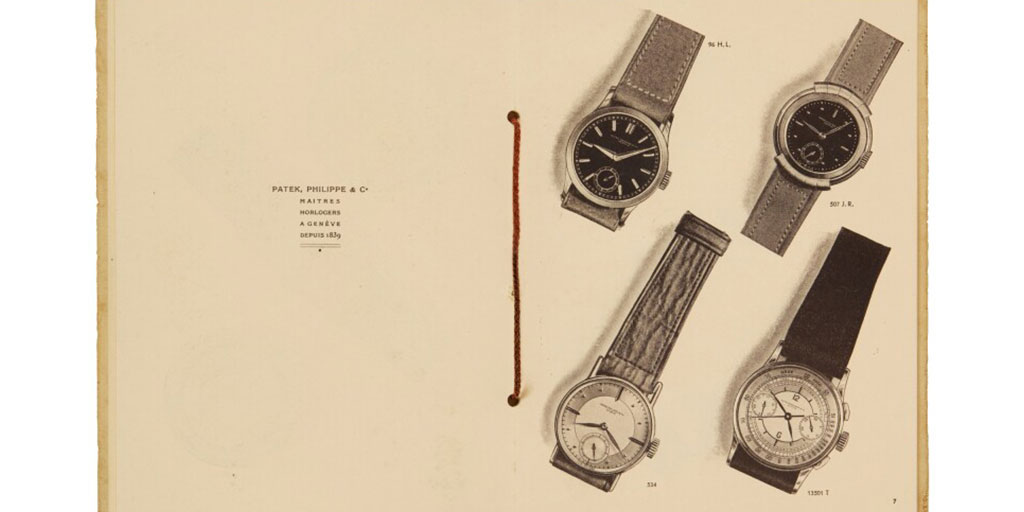

The ref. 507 is one of the most interesting timepieces that seems to be largely undiscussed. Perhaps this is due to the fact there were so little produced. My encounters seeing these with black dials have been quite limited, most recently through the newly published book ‘My Dream Collection’ by Ali Nael and Eric Tortella. It features a radical design from the 1930s which makes it even more of a standout timepiece within the manufacturer’s catalogue.

Nicknamed for its “ribbon hooded” aesthetic, these triple stepped cases were constructed from Georges Crossier, and feature the stylized two-tone hooded lugs. Some models will feature a fully painted sector dial, with feuille hands, while others such as the present example incorporate baton hands, and applied numerals with minute markers on the periphery of the dial. A later model than the one featured within the museum’s collection (movement No. 825 841) was sold at Antiquorum. Sotheby’s New York sold another two-toned version, but without white metal on January 25th, 1990. Its movement was No. 825 873 and it did not feature a black dial.

Over roughly the past four – five years I have kept an eye out for ref. 507s. To finally witness one outside of the bound pages of books and catalogues was very much an experience I will fondly remember.

One of the complicated wristwatches that I first read about in Stacy Perman’s book ‘A Grand Complication: The Race to Build the World’s Most Legendary Watch’, was a wristwatch sold on April 20th, 1996 at Antiquorum Geneva. This was no ordinary complicated timepiece. It was a wristwatch that quite literally represented the epoch of watchmaking throughout the 1930s. Originally cased in 1930, it would undergo a transformation over the course of nine years by the complication specialist Victorin Piguet. The Valle de Joux is widely recognized as the heart of horology after surpassing Germanic and English watchmakers during the 19th century. Within the region, only a handful of families laid the foundation for what the Swiss watchmaking industry would heavily rely on when consumers commissioned the most advanced timepieces of the era. This particular Calatrava was uniquely special in the fact it ushered in a new respect for wristwatches at auction. According to Antiquorum, it was sold for a record-breaking price of CHF 185,000 on 4 October 1981. As Perman notes within her celebrated publication, it would subsequently become the first wristwatch to be sold for over $1,000,000 in 1996. During this sale, and within Martin Huber and Alan Banbery’s book ‘Patek Philippe Geneve Wristwatches’, the watch can be seen on a platinum bracelet. At the museum, however, it stands amidst other Calatrava wristwatches on a leather strap. The platinum minute-repeating astronomical timepiece features applied Arabic numerals; however it is worth emphasizing that these are presented in the uncommon radial format. The calendar apertures are presented in the “American” (linear) style. The weekdays are depicted at 9 o’clock, while the month is indicated at 3 o’clock. The central blue hand incrementally moves each 24 hours to emphasize the day of the month. This important watch bears the movement No. 198 340. Considering this highly complicated timepiece is only 30.2mm wide (39.2 lug-to-lug) and 10.9mm high, it is astounding to imagine the work that went into making this advanced movement.

Beyond the “Le Presse-papiers” (paperweight) desk timepieces belonging to James Ward Packard, my fascination with Patek Philippe clocks is fairly new. The incredible timepiece was sold to James Ward Packard on June 7, 1923. Witnessing the twin barrel, eight day power reserve desk clock gave me a great sense of privilege. To have finally encountered the timepiece was a very special moment, particularly in such a short period after the release of Patek’s 2021 Only Watch. Yet, I was taken aback by the fact that the subsequent model which Tiffany & Co. had sold to Henry Graves Jr. in 1927 was less than ten feet away! I had not anticipated this desk clock would be in the museum, so it was a wonderful surprise. It is worth noting that the Graves Jr. desk clock is on view with a few other timepieces that are not owned by Patek Philippe. However, they were graciously given permission to look after them for the next generation of watch lovers visiting from around the world.

I’m ashamed to admit it, I’ve never taken the time to understand the ref. 828HU. At a glance, one can notice this incredible cloisonné enameled table clock is attributed to the brilliant Louis Cottier. This might be more straightforward from an aerial perspective of Cottier’s World Time System, the museum houses a section dedicated to the French watchmaker’s monumental contribution towards the manufacturer. While I was initially entranced by the bras-en-l’air pocket watch ref. 784 (also known as The Crow & The Fox), I would return later to Cottier’s Pantheon of creations to admire this exquisite masterpiece.

Beyond the dial’s depiction of Mexico, a 360-degree presentation highlights the artisan’s work of the northern hemisphere. Considering the high failure rate of enameling, the dial alone makes this preserved work of art an absolute relic. There is certainly an argument to this being one of the most important of Cottier’s World Time models. The “Heure Universelle” ingeniously incorporates 30 different time zones. In addition, the massive 21 ligne movement features an eight-day power reserve.

The table clock stands just under two inches (50mm) high, and 4.8 inches (122mm) wide. Completed in 1952, the timepiece features the later “lys” hour hand which was cut by Cottier himself. The 24-hour hour ring also incorporates a detail found in early World Time models in the sun and moon (which likely were also hand-engraved by Cottier). From a birds’ eye view, one can see Cottier’s use of the octagonal base which decades later would go on to become such a coveted design within timepieces.

Within The Uhrenmuseum Beyerthe book ‘Uhrenmuseum Beyer Zurich Neuerwerbungen’, an earlier, slightly different table clock resides which is dated to circa 1938. On November 14, 2004, Christie’s Geneva sold this exact timepiece for $402,204. The clock would later be published on HODINKEE while reporting on the reference 828 HU’s inclusion at The Patek Philippe Grand Exhibition of New York.

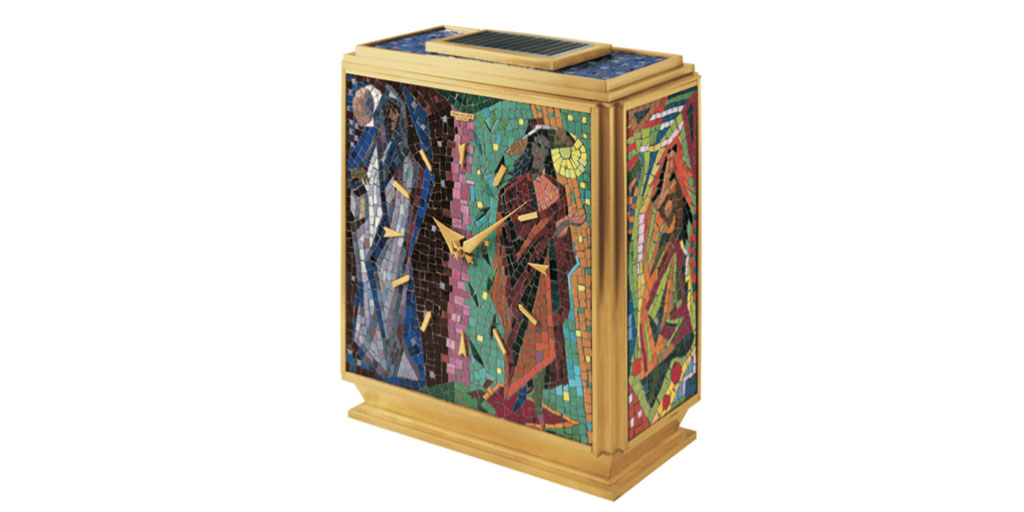

Only recently did I begin to understand how impressive Patek Philippe’s photoelectric desk clocks were. The second floor contained a magnificent section highlighting a range of enameled photoelectronic timekeeping. An immaculate mosaic example made by Mademoiselle Pellarin-Leroy exists. The vibrant ceramic-mosaic features applied gilt-brass indexes encased in a gilt brass case designated as number 201.This timepiece is powered by the caliber 17-250, which was also used within several clocks from the manufacturer such as the ref. 701 and ref. 815. This movement is the marriage between 19th century technology powered and solar technology, developed by Patek Philippe in the 1950s and 60s. Within a 1958 video titled ‘Novelty Watches’, this fascinating desk clock can be seen along with other creations of the era highlighted at the International Watch and Jewellery Fair, London. The narrator emphasizes within the video how this astonishing clock can be purchased for a mere £1,800.

Interestingly, I noticed a void of Patek Philippe coin watches on view. I’d imagine that Patek Philippe does have several examples within their collection, but the fact there were none featured within the public collection was a bit perplexing. Particularly when one considers the fact that the manufacturer has a significant place within the genre’s history, devoting an entire line of coin-form timepieces. Within Nicholas Foulkes’ ‘Authorized Biography of Patek Philippe’, there is an interesting story in relation to the Stern family’s leadership in which the president will toss a family owned Patek coin watch into the air to make the announcement of the next president. Perhaps one day in the future we will be able to see a new section within the museum including the Stern’s personal coin watch. It doesn’t seem to farfetched in that other family members’ watches can be seen on the top floor.

Witnessing so many timepieces created by Patek Philippe and many earlier watchmakers, I had a moment of clarity. Despite the museum being Patek Philippe’s, it was clear that much of the inventory was made up of timepieces created by other manufacturers. While those timepieces certainly were fascinating, my primary focus was on Patek Philippe’s catalogue. Yet the decision to house so much history, expanded beyond the brand’s own, was a large takeaway. The museum is certainly one of the most special locations I have had the privilege to visit. One could spend a lifetime learning inside the building.

My strategy in visiting the museum came from several individuals who echoed the same advice: “You cannot go for just one day!” After leaving the museum for the second day in a row, I could feel a bit of the adrenaline wearing off. I thought back to the advice of those who had made this journey, some on several occasions. Walking away from the doors, I wanted to urgently turn around, and look for more timepieces to discover. If I could impart one piece of advice to those who are deeply passionate and have not made the trip, I would certainly encourage booking a tour. Perhaps, if you have invested a great deal of time learning about the brand, genres and references, it is best to explore independently on one day, while taking advantage of the guided tours on another day. I was amazed at the museum’s ambiance. It was an eye-opening experience. Hopefully, some of the selected pieces can excite those eagerly planning their visit.