On March 7, 2025, Jean-Pierre Hagmann died at the age of 84. His passing was a huge loss to the world of horology. Although he may not be a household name, he was the world’s most gifted individual case maker, with a talent we may never see again. For collectors of fine Swiss watches, to see the initials JHP on a case is like finding the holy grail: an added value indicating that the case was designed and made by the hands of a craftsman, not a machine.

Born in 1940 to Swiss German parents, Hagmann led a life that was anything but ordinary. From birth, he was hard of hearing and had to attend special schools. It is ironic that such a disability did not prevent him from becoming the maker of the very best cases for minute repeaters — the clarity of sound that resonates from his cases is simply unmatched. It has been said that a master craftsman sees with their hands. JP Hagmann grew up in what he called “a manual family” that had “always been makers of things.” He made his own toys out of wood and cardboard. He then built his first bike, and even his first car by taking apart an old model and rebuilding it in four to five months. “I can build anything with my hands, but it needs a lot of thought and reflection,” he said, “Before starting a project, I do research, find books on the subject and study people that make things, so that I can learn from them.”

No engineering issue was too difficult for him to solve. As he told his friend Helmut Crott, “If you have a complex mechanical problem, you have to break it down into many small steps.” On another occasion he professed, “I’m lazy by nature, so I always look for the simplest and quickest technical solution which is often the perfect one.” This “simple approach” led to solving some of the most complex horological challenges.

Anyone who had the pleasure of meeting Hagmann would say what a delight he was to spend time with. He always had a twinkle in his eye and a good story to tell. “An evening with him was always too short,” said his friend Peter Friess, Director of the Patek Philippe Museum. Such charm probably came from his early love of comedy and performance. At the ages of 16 and 17 he made comedic floats for the Geneva Festival. With the money he made from this, and participating in the festival, he brought his first pair of ice-skates. As with every new hobby, Hagmann became an expert and spent the next 10 years performing on and off for the TV show Holiday on Ice, usually playing the clown and making people laugh.

His mother recognized from early on that he would “always be wearing a white coat” and encouraged him to train as a jeweler at Geneva’s School of Fine Arts. In 1957, he became a trainee with Ponti Gennari, a renown jeweler whose workshops were in Atelier Rèunis, the building which later became home to the Patek Philippe Museum where many of Hagmann’s masterpieces are on display. Ponti Genari introduced the young Hagmann to the world of watchmaking as the company was a famed chaîniste making exceptional watch bracelets for companies like Patek Philippe. In 1961, he moved to another chaîniste jeweler Gay Frères where he spent a year putting bracelets on Rolex watches. This he found boring and decided to return to what would become his lifelong passion – restoring and riding vintage motorbikes.

In 1968, Hagmann officially started his career in case making when he joined Gustave Brera and quickly gained a reputation as a highly skilled technician. However, it was not until 1971 when he joined chaîniste Jean-Pierre Ecoffey that Hagmann’s unique approach to constantly improving production was translated into watch cases. Soon after his arrival, Ecoffey purchased case maker Georges Croisier (later known as Genevor SA) and Hagmann was put in charge. He immediately used his instinct and hands-on experience to reconfigure the case-making machinery and tools, reorganize the work processes and train people. After 12 years of managing the case department — “power is exhausting!” he joked about this period — he took a brief stint at dial making and joined Stern Création. Once again, he used his instinct and innate ability to understand every detail of a process and then improve it to develop new dials and stay ahead of the competition. But he was not happy, and for the first time in his life: he was fired from a job. This inspired him to start his own company.

In 1984, Hagmann opened his own case making workshop in Geneva. Even though he was known for his brilliant work, it was a challenge to start from scratch. As with every new endeavor, he made the most of his own abilities and autodidacticsm. He couldn’t afford much machinery, so he modified and improved what he had. He could not afford many tools, so he made what he needed. Hagmann was a problem solver and this in turn led him to supply the greatest watch houses. For the next 30 years, he worked for 33 clients including Svend Anderson, Acrivia, Audemars Piguet, Concord, Breitling, Blancpain, Hublot, Franck Müller, Movado, Vacheron Constantin and most famously, Patek Philippe. It was through these high-end watchmakers that he was able to learn the classical rules of case making. Once these rules were mastered, only then could he break them, simplifying his production techniques, but without ever sacrificing quality and aesthetics.

Working with his first client, Svend Andersen was where Hagmann learnt to work on minute repeaters and pocket watches. These skills soon led to Patek Philippe becoming his biggest client for whom he worked exclusively on minute repeaters and grand complications. “He was the man for special cases no one else could make,” said Peter Friess.

Even with his hearing disability, Hagmann mastered what many believe to be one of the most challenging aspects of watchmaking: making a case that maximizes the resonance of a minute repeater. “His watches sound like a bell. That’s why everyone wanted him,” says Friess. Hagmann believed that smaller and lighter cases produce a better sound for minute repeaters, with gold being a superior metal to denser platinum. Hagmann singles out rose gold as the best metal for a repeater case because the composition of the material makes it stiffer than other gold alloys. He believed that a repeater watch case should be no thicker than 0.5 mm on each side of the movement and the crystal should be domed.

One of his important case innovations is the recessed track on the side of the watch case for the repeater slide, a development that is now industry norm. Historically, the slide was mounted in the surface of the case side, attached on the inside with a screw which according to Hagmann meant occasional instability and off-center alignment.

Time that you can hear as well as see has been a Patek Philippe specialty since the company’s founding and to celebrate the importance of bringing all its workshop together at Plan-les-Ouates in 1997, the company created the minute repeater ref. 5029. To accommodate the slide for the minute repeater on the side of the case, the hinge of the caseback opened under the winding crown at 3 o’clock instead of at 9 o’clock. This ingenious case design was made by Hagmann and is now an industry standard.

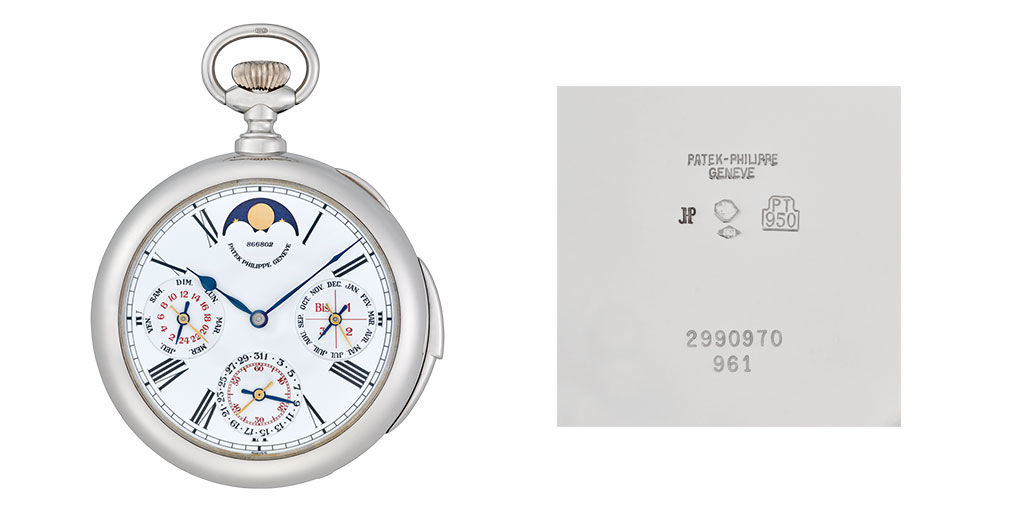

Hagmann’s magnum opus was the Patek Philippe Star Caliber 2000. It remains today one of the world’s most complicated timepieces, and thanks to its ingenious case, one of the most beautiful. Hagmann was challenged with having to produce a case which enabled each of the 21 complications to be accessed as well as the sound of the Westminster chime — a replica of Big Ben’s chime in the U.K. Houses of Parliament. To add to the difficulty, Hagmann had to make four cases in yellow, rose and white gold and platinum, plus an additional four in platinum for a special fifth set. The prototype case can be seen in the Patek Philippe Museum, ironically, a mere 10 meters from where Hagmann used to work when the building was Atelier Réunis. Hagmann developed a bassine-style half-hunter case with a sprung cover on both sides of the dial revealing as many of the dials and complications as possible. To open the cover of each side separately, Hagmann and his team at Patek Philippe developed an ingenious, patented rotating pendant system. With slight pressure, the entire pendant can be turned 180°. A Calatrava Cross indicates the side on which the cover will open.

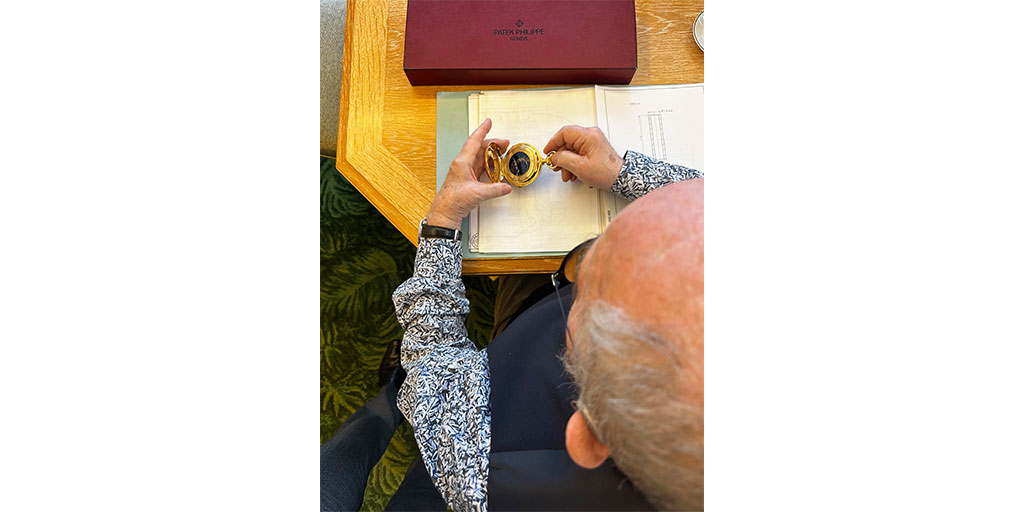

Collectability founder John Reardon met Hagmann recently in Geneva and he told him a little-known fact that distinguishes each of his watch cases: “they all open to an angle of 82°, because this, in his opinion is the best angle to view the movement or cuvette underneath!”

Such a genius case and mechanism were invented not by a computer, but as with every one of Hagmann’s innovations: a pen and paper. “I was probably the last case maker in Switzerland who could do everything himself,” Hagmann had said, meaning that he could design a case calculating every angle and measurement, create a prototype, construct, polish and finish — every detail. For Hagmann, harmony is paramount, “harmony in size, volume, color, aesthetic, ratio, it’s a magnificent word,” he had said. Without the aid of a computer, Hagmann would work in two dimensions which is much more difficult — and the ultimate test to his skills.

It is estimated that Hagmann produced an extraordinary 1,500 cases for minute repeaters, at least a third of which were made for Patek Philippe. Collectors are most likely to find the precious JHP stamp on Patek Philippe minute repeaters such as the ref. 3979 of which 75 pieces were made in yellow gold, 12 in white gold and 12 in platinum. The JHP monogram can only be seen on the first cases of the minute repeater with perpetual calendar ref. 3974, later cases were stamped with the Ateliers Réunis mark. The same situation applies to the grand complications ref. 3939 and ref. 5016 both with minute repeaters and tourbillons. Hagmann made the first cases in each of the metals yellow, rose and white gold and platinum; Atelier Réunis made the remaining pieces. There are a few special cases such as two ref. 3448 in platinum (one was made for Jean-Claude Biver), as well as 15 unique pocket watches that Hagmann made for the marque.

Beyond the big names, Hagmann also produced cases for many of the independent watchmakers of the 1980s and 1990s, including Franck Müller, for whom he developed the case for the very first dial-side tourbillon wristwatch in 1984, and the first Cintree Curvex case. In 2016, he sold his business to Vacheron Constantin and retired in 2017. A mere two years later, a call from Rexhep Rexhepi encouraged him to return to work and open a case workshop for Akrivia.

A somewhat morbid story that Jean-Pierre Hagmann loved to share really sums up the importance that one man wielded in the world of watchmaking. About 20 years ago, Hagmann had a serious motorbike accident during a mountain rally and badly damaged one of his eyes. When he was transferred to a hospital in Geneva, he was visited by the heads of all the top watchmakers. Each of these titans then personally asked his doctors to do whatever it took to repair his eye; all expenses would be covered.

Eventually, after almost 70 years in the industry, Hagmann was recognized for his brilliance. In September 2024, he received the Prix Gaïa for artisanal craft and creation. In his acceptance speech to what many believe is the Nobel Prize of the watch industry, Hagmann said with pride, “During my long career, I have improved practically every production step in the manufacture of handcrafted housings.” Two months later he received the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Grand Prix d’Horlogerie de Genève (GPHG) in which he thanked his very long list of clients representing the who’s who of the watch industry.

Just before he passed, Hagmann was excited to start a new chapter which brought him back to his roots as a jeweler: he was to set up a workshop with the last great chaîniste Laurent Jolliet. This together with a mandate to produce the case prototypes for the newly relaunched Universal Genève, showed that Hagmann’s life was certainly not slowing down. In fact, the day after he died, he was due to participate in a mountain rally on his beloved 1925 motorbike.

When asked what he would have done if he wasn’t a case maker, Hagmann said he would have been an organ maker. The physics of combining materials with sound is not so different from his chosen profession. Thankfully, the man who prided himself on always working on his own and simply using instinct and his hands, chose to invest his phenomenal skills in watchmaking.

June 2025

If you enjoyed this article and our educational content, please take a moment to rate Collectability on Trustpilot.

This article also appeared in Revolution Magazine.