Many of the world’s most gifted watchmakers have worked for Patek Philippe. A select few were part of an elite group known as the régleurs de precision or adjusters. These men and women were on a constant quest to make the most precise, mechanical timepieces. They flourished during a period when absolute time accuracy was an elusive concept rather than readily available on a phone or computer. Recognition of their mastery of time was to achieve an Observatory rating for a movement that they had precisely regulated. Entering a movement into the Observatory Competitions was the ultimate test for a watchmaker and there was no higher honor in the industry than to be recognized in this exclusive club. Watch companies valued adjusters as their most important watchmakers, in part because of the attention the chronometric timing competitions would receive during the mid-20th century. Observatory wins would be advertised and seen to contribute to commercial success. Prizewinning movements were often cased and sold with their bulletin de march (or rating certificate) from the Observatory and remain to this day much sought-after by collectors.

Referred to affectionately at Patek Philippe as “les anciens”, adjusters were superstars and reportedly received about three times the pay of other watchmakers. They made their own hours, worked their own way, had their own individual methodology and did whatever was needed to win the coveted Observatory ratings. Their job was to perfect ‘the diverse factors which affect the rate of the watch, such as shocks, changes of position, variations of temperature and barometric pressure, clearance of the balance spring, defects of poise of the balance and spring, the effect of the maintaining impulse, friction, etc.’ In short, these were the masters of the master watchmakers. At Patek Philippe, names such as Max Studer, Paul Buclin, André Bornand, Henri Wehrli, Charles Beausire and François Modoux are legendary in the world of adjusters, yet one name is recognized as the best of the best, André Zibach.

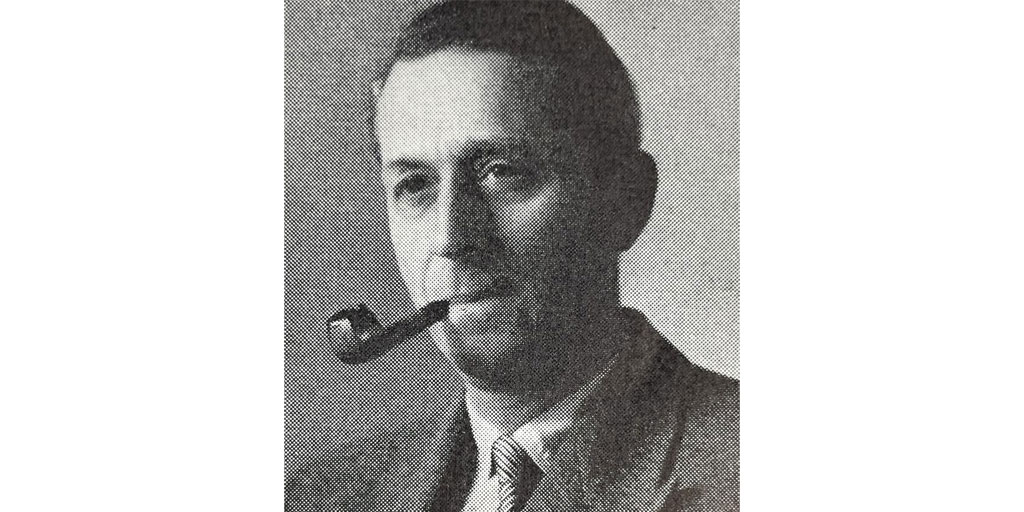

André Zibach was born on April 30, 1904, in La Chaux-de-Fonds and studied at the Geneva School of Watchmaking. He was an outstanding student and graduated with impressive diplomas and qualifications including Horloger-Régleur on June 30, 1921, and Regleur on June 30, 1922, the year he joined Patek Philippe, a company that would benefit from his genius and gift for watchmaking. In addition to winning numerous awards from the Kew and Geneva Observatory Competitions from 1929 onwards, Zibach is credited as the inventor of the Gyromax balance.

To be an adjuster at Patek Philippe, particularly during the heady days between the 1940s and the early 1960s when the company dominated the Geneva Observatory competitions, meant much more than being a celebrity watchmaker. To be worthy of such a title required a lifetime’s experience of watchmaking, an inventive and curious mind, and a genius with which to achieve every fraction of a second of accuracy from the assembly of movement parts. These master adjusters were often likened to Grand Prix racing in which an adjuster was both the driver and car designer; winning an Observatory prize or a Formula One race was the highest accolade, but just a part of the real achievement. Patek Philippe felt it was important to stress the connection between the watches that its customers wore and the timepieces that were entered for Observatory competition noting in a company newsletter in 1954 that the “technicians who make these prizewinners are the same men who take part in the supervision of all Patek Philippe watches, not merely engaged to build special Observatory entries.” Any aspiring adjuster employed by the company would have understood he or she was joining a tradition that started with Jean Adrien Philippe, who is recorded as having personally regulated several chronographs. They knew that their contribution to Patek Philippe was of unparalleled importance – and extremely challenging.

Until quartz timekeeping was widely used to give the most accurate time, adjusters had to verify the timings of a movement they were working on mechanically each day by means of a radio. Adjusters called a radio outlet at a precise time every day to check the exact timing of a radio signal. The radio center also sent an electromagnetic signal on a paper strip that came by telegraph. Combining the electromagnetic method with their own eyes and ears, adjusters were able to obtain an accuracy to within one-tenth of a second. Adjusting and regulating movements to be the most accurate possible was competitive work and rivalry was intense, not only between manufacturers, but also between adjusters under the same roof who worked side by side, but who kept their timing secrets jealously guarded.

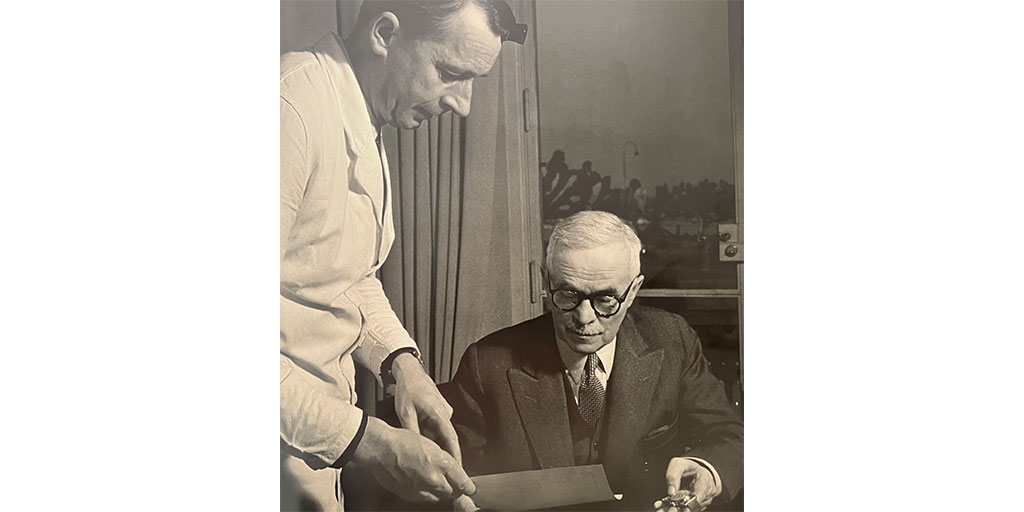

André Zibach worked at Patek Philippe from 1922 until 1960, an exciting and dynamic period, with both highs and lows in the history of watchmaking. He was able to develop all his skills to their utmost potential and fulfilled a succession of rolls until his retirement. Between 1950 and 1952, Andre Zibach and Eric Jaccard constructed a tonneau-shaped wristwatch movement with lever escapement, caliber 34 S, which successfully took part in the Geneva Observatory chronometer timing competitions. In 1956, Zibach was appointed deputy technical director (under the legendary Jean Pfister), with direct responsibility for the research and development laboratory. He was later the natural choice for the head of the chronometer department.

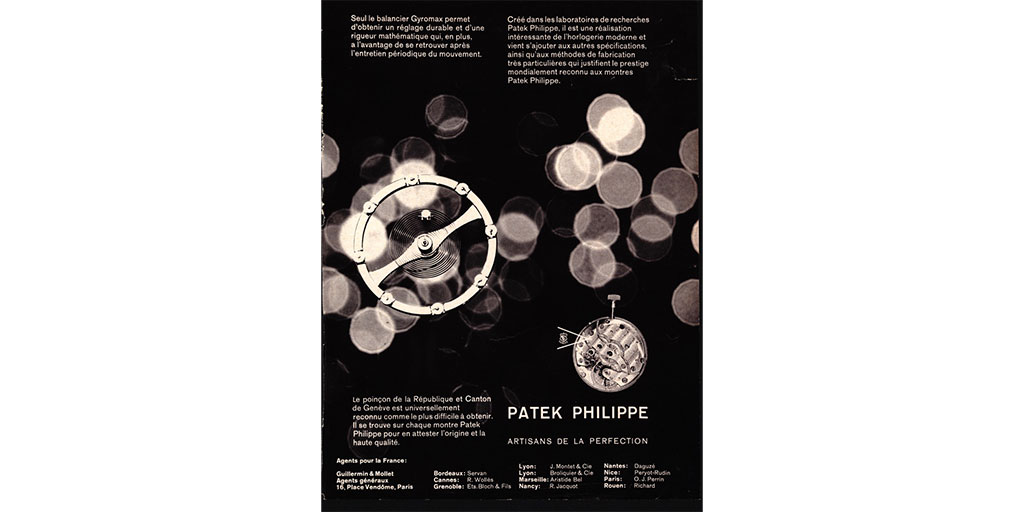

It comes as no surprise therefore that because André Zibach was the master of accuracy, he would be a critical member of the team responsible for one of the most historically significant improvements in the development of the wristwatch: the Gyromax® balance. Zibach knew how to think outside the box, and he took his theoretical knowledge to a new level with his invention of a Glucydur balance which became known as the Gyromax® balance. Patented twice, first on May 15, 1949, with Swiss patent No. 261 431 and again on December 31, 1951, with patent No. 280 067, the Gyromax® balance revolutionized not just watch production at Patek Philippe, but also the watchmaking industry around the world. The balance assembly is referred to as the heart of the watch – the tiny, coiled spring tethered at one end to the balance staff and the other to the balance is what accounts for the comforting tick-tock of a timepiece. First introduced into pocket watches in the second half of the 17-century, it revolutionized accurate timekeeping and personal, portable watches became a reality.

Zibach’s genius was to aggregate the advances in metallurgy (Glucydur is an extremely hard, antimagnetic, stainless alloy of beryllium bronze) and watchmaking technology and conceptualize the balance spring in a completely different way. The best level of accuracy is achieved with the biggest diameter balance wheel that can be accommodated in the movement. This is not an issue with a pocket watch, but as wristwatches became smaller, the need to improve the accuracy of the balance wheel became more challenging within the confines of space. Andre Zibach’s improvement was to eliminate the screws on the circumference of the balance wheel and replace them an octet of slotted weights set horizontally into the upper edge of the balance wheel. It was now possible to enlarge the balance wheel diameter considerably, contributing a notable increase in rate accuracy. Or as Patek Philippe’s technical department put it at the time, “increasing the moment of inertia of the balance wheel to the maximum space available.” A further benefit was that the balance assembly did not have to be dismantled to enable the watchmaker to reach the screws on the side, which had to be adjusted then reassembled, tested again, until by trial and error the best level of regularity was achieved. Because of the slot, the weights were lighter on one side than on the other and could be turned to regulate timing without removing the balance cock. Like so many brilliant inventions, the concept was easily grasped and welcomed by the watch industry. The Gyromax® balance was officially introduced in 1953, the same year that Patek Philippe presented another technical step forward, the self-winding movement with Swiss patent No. 289 758 on March 31.

Even today, long after the era of great Observatory competitions has faded into history, the legend of champion adjusters like André Zibach can move collectors to pay millions at auction for a watch adjusted by his expert hands. An example of such a watch which left Patek’s workshops in 1952, appeared at auction in Christie’s Geneva in November 2012. This ref. 2458 time-only watch, with a sub-dial at 9:00 o’clock for the seconds (rather than at 6 o’clock as on other ref. 2458s) was the property of a Texan lawyer called J.B. Champion. He was so proud of this important watch that he had a special dial made which in addition to displaying the number of the movement’s bulletin de marche No. 861121 issued by the Geneva Observatory, identifies him as the owner with the words, “Made especially for J.B. Champion.” It sold for a staggering CHF 3.7 million, a record for a time-only watch. Part of this extraordinary price was because André Zibach was responsible for adjusting the movement for this watch and securing its prestigious Observatory rating.

Preparing and regulating a chronometer for an Observatory trial is one of the most difficult and painstaking tasks in the field of watchmaking and requires an incredible depth of knowledge, understanding and experience by the adjuster. Zibach lived in a stressful world of life or death based on precision adjustment, especially when preparing watches for Observatory trails. In an article from the Swiss Journal of Horology in 1950, the question was asked, “Is it surprising that adjusters who deal with Observatory work sometimes suffer from nervous exhaustion and become cantankerous and crusty, finally becoming disgusted with their profession?” However, there was a cash incentive related to winning an Observatory prize which helped relieve the pain, especially for Patek Philippe adjusters. In an interview in the Patek Philippe Magazine Vol III, Number 10, Max Studer, another legendary adjuster who to this day holds the highest ever Observatory result, scoring 56.34 points out of a possible 60, recalls the anticipation of receiving a bonus. ‘After the Observatory competitions in February, the results were announced, and bonuses were awarded by Mr. Stern [the then President Henri Stern] according to the number of points each piece had won. “One year, my envelope was rather thin and Stern said to me, ‘Studer, chronometry costs a lot.’ I was not happy. But the following year I won all the first prizes. Handing me a fat envelope, Stern said to me again, ‘Studer, chronometry costs a lot.’ I was a bit surprised to hear the same sentence from him again and looked up to see a mischievous expression on his face. He was teasing me!”’

Incredibly, Zibach’s hands regulated most of Patek Philippe’s 30 mm competition chronometers and many of his entrants performed extremely well. Since 1945, when the wristwatch category was added to the competition, Patek Philippe won many first prices, notably in 1948 when the manufacturer not only won the First Prize, but also the Third Prize for the J.B. Champion movement no. 861 121. Another movement from this series, number 861 119 was exclusively regulated by André Zibach and repeatedly submitted over a ten-year period from 1948 to 1957. Remarkably, the watch won First Prize three times in 1948, 1954 and 1956 and was therefore the only watch ever to win First Prize more than once. Until 1966, when such competitions were ceased due to the arrival of electric and quartz watches, Patek Philippe won an impressive number of 12 trials.

To date, only two Patek Philippe timepieces were known to have been owned by André Zibach. The ref. 1582 is historically important because it contains the first prototype Gyromax® balance. As we know, Zibach is credited for this important invention and in this watch, he replaced the standard lever escapement, which was originally in this 1947 model, with the first Gyromax® balance that he made himself. The watch features a presentation engraving to Zibach celebrating his first 25 years of service at Patek Philippe. This watch was probably presented to him by Henri Stern himself as Zibach’s invention and contribution to the company on so many important levels was in a league of its own. The watch was sold at Christie’s in 2016.

The other personal timepiece that belonged to André Zibach was a unique watch that he made as a wedding present for a close friend. Zibach made the movement in 1929, a mere seven years after he started as a watchmaker at Patek Philippe. The Extract from the Archives states that the movement was sold to Zibach on October 28, 1936. It also notes that the silvered dial with gold markers was made by Stern Fréres to go with the 9 ligne movement with anchor escapement that was originally manufactured by Zibach in 1929.

The Archive confirms that the watch was purchased in 1936 without a case, but the final watch case is stamped with the Patek Philippe signature and movement number 822 397. This suggests that Zibach commissioned the case separately from Emile Vichet (noted by the Poinçon de Maître key 9) rather than buying it from Patek in order to save money, something a young watchmaker would most likely need to do. The simple but elegant case features downturned lugs and a flat, thin case back. The case design is similar to cases made by Vichet for the ref. 130 chronograph. Vichet also made cases for iconic references 1526 and 1518, as well as early models of the references 2497 and 2499. Zibach obviously knew exactly which case maker was the best to make the case for such an important, personal watch.

In 1929, when André Zibach started to work on a Patek Philippe watch for his friend, he purchased a more affordable rectangular watch for himself and had his name boldly inscribed on the dial. Recently discovered by Collectability, we can assume that Zibach wore this watch until he was presented with the ref. 1582 in 1946 which incorporated the first prototype Gyromax® balance. The rectangular watch has a round movement signed by Tavannes number 67918. The dial of the 18K gold case is engraved and enameled with “André Zibach Geneve” a fitting testament to one of the greatest watchmakers of the twentieth century.

Even Philippe Stern, honorary president of Patek Philippe, is the proud owner of a watch adjusted by André Zibach. Athough the watch was personally worn by Philippe Stern, it has a long history. It was made by master watchmaker André Bornand (1892-1967) who was a professor at the Geneva School of Watchmaking and one of the best tourbillon specialists of the 20th century.

The exceptional tourbillon movement 861 115 was completed in 1945 and specially adjusted for the Geneva Observatory trials by Bornand’s old student, André Zibach. He adjusted this watch seven times between 1948 and 1959. Adjusting a tourbillon movement to Observatory standards is the most difficult and challenging achievement for a watchmaker. Once again, André Zibach excelled and proved himself to be the rockstar of watchmakers. The movement has a bimetallic Guillaume balance and steel Breguet overcoil, and vibrates at 21,600 vph. Described by Jack Forster in Hodinkee as “the single most truly badass – in every way possible – personal daily wear wristwatch I’ve ever seen.”, the watch can now be seen at the Patek Philippe Museum.

Today, Patek Philippe still has extraordinary watchmakers developing movements and perpetually striving to build the most precise mechanical watch. This quest for perfection is aided by computer technology and new materials such as Silinvar® that could not have been imagined in the days when André Zibach was working studiously at his workbench, puffing on his pipe and dreaming of perfect time.