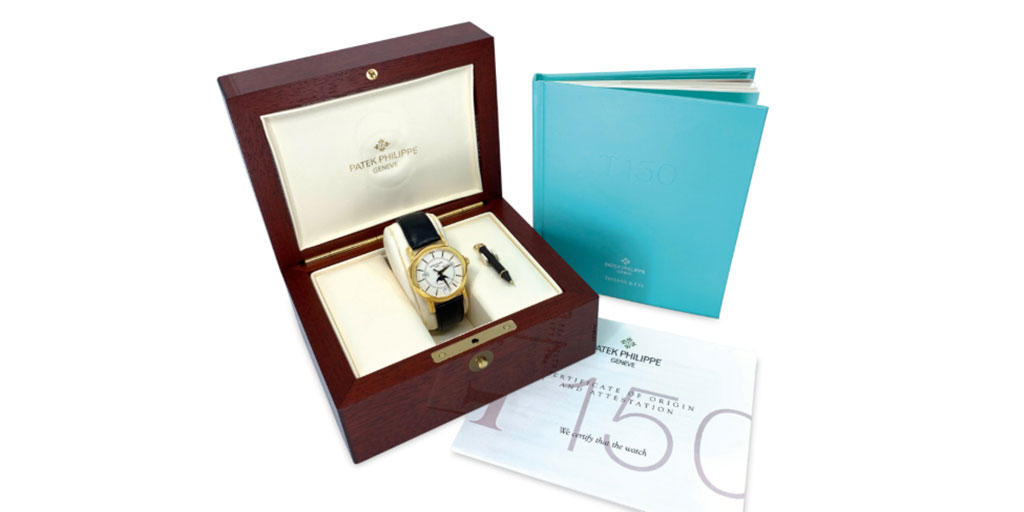

Since the mid-19th century when clock and watchmaking started to leave the hands of a single watchmaker and moved to manufacturers that could produce to scale, cases have been produced by specialist case makers. Reputations of these case makers varied, but companies like Patek Philippe only worked with the very best, most established makers. Some case makers started as jewelers, others established a reputation based on innovation and the use of new metals such as steel or the creation of waterproof cases. Case manufacturers would produce a catalog displaying the various case shapes that they produced. A watchmaker would then select the case that best complemented the new movement they had created. Dials were also selected from a catalog issued by dial makers. Nowadays, elite watchmakers like Patek Philippe design and produce their own cases in house, and this remains the exception to the rule. Most watchmakers still use specialist case makers for their case production.

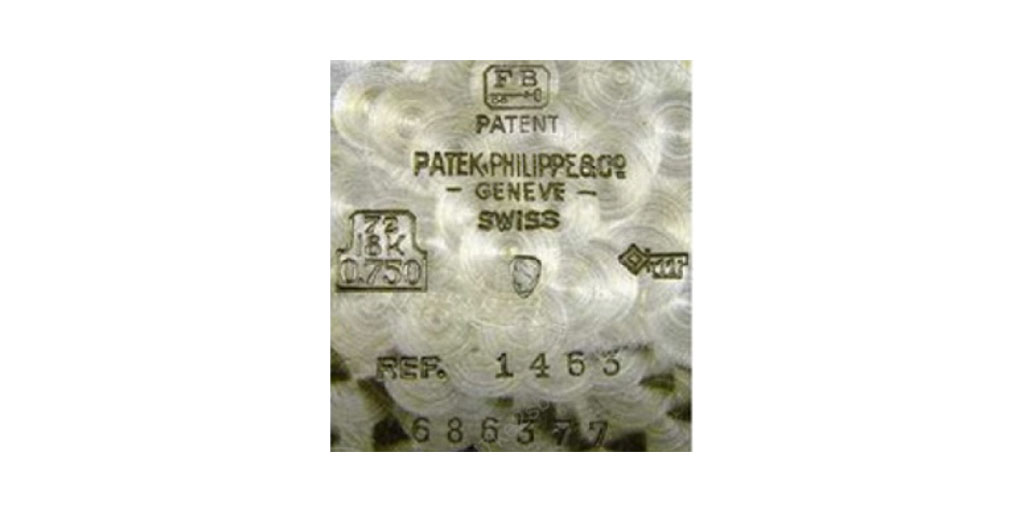

Identifying which Swiss case maker made which vintage Patek Philippe case is simply a matter of understanding the numbers stamped on the inside of a case back, either within a key or hammer head symbol. Patek Philippe never wanted to identify a case maker by its name because case makers supplied other watch manufacturers, and all cases were ultimately hand-finished by Patek. Other Swiss watch makers also did not want to identify their case makers so for cases made of precious metal, a system of marks and code numbers was devised by the association of watch case manufacturers, with different symbols representing the different case making regions of Switzerland, principally Geneva and the Neuchâtel and Jura regions. Under the Precious Metal Act of 1934, a specific case manufacturer numbering system was introduced as law on July 1, 1934. Each case manufacturer had to register their Poinçon de Maître with the Central Bureau for the Control of Precious Metals in Bern. This type of mark is called a “Collective Responsibility Mark” because the same mark was used by all the members of the association within the region, with an individual number to identify each member. Numbers within a key symbol denote that the case manufacturer was based in Geneva. Numbers within a hammer head symbol denote that the cases were made within the canton of Neuchâtel with a ‘C’ for La Chaux-de-Fonds or an ‘L’ for Le Locle. As part of its quest to produce as much as possible in-house, Patek started acquiring case making companies, most notably, Ateliers Réunis and its associated case makers. The Atelier Réunis building is now home to the Patek Philippe Museum. Case makers now owned by Patek Philippe stamp their cases with an oval PPCo.

Patek has always pushed the boundaries of its suppliers, for example, during the 1950s and 1960s, when Gilbert Albert was designing shaped cases that had never been produced before, case manufacturers had to learn new techniques. Arguably, the most pivotal change in the way cases were made to scale came with the introduction of the Ellipse collection. Case makers did not offer an elliptical-shaped case in their catalogs, thus new production techniques had to be introduced. In the case of Ellipse cases, Patek case designer Jean-Pierre Frattini worked primarily with F. Baumgartner (Key Number 2), Wenger (Key Number 1), and Ateliers Réunis (Key Number 28). The last cases were made by Favre-Perret in La Chaux-de-Fonds before modern production was brought in-house at Patek. The company would employ various case makers to produce similar case designs primarily to expedite delivery. As with all components used in watchmaking, case production to Patek Philippe’s specifications is a time-consuming process and one of the reasons Patek has brought as much production as it can in-house. This is the only way that Patek can ensure that its exacting standards are met.

For collectors of vintage Patek Philippe watches, understanding case makers is an important part of the collecting process. There are collectors who will only buy a watch if the series was made by a specific case maker. It’s important to note that rarely did one case maker produce cases for an entire collection, or even a series. Even iconic watches such as the refs. 1518 and 2499 had two or more case makers producing cases, including during a production series. Equally, identifying that a watch case was made by one of the most esteemed case makers can add to the value of a piece.

Since its inception in 1839, Patek Philippe has worked with around 28 known case makers. In the following list, we will identify the most well-known and most often identified case makers via their numbers, several of whom produced cases for some of the most iconic and important timepieces ever made. In addition to key or hammer numbers, case backs also feature other stamps identifying for example, gold and platinum (with numerous variations of the ‘Helvetia’ Swiss precious metal hallmark), additional platinum and steel hallmarks, case production series numbers plus various import marks. These will be discussed at a later date.

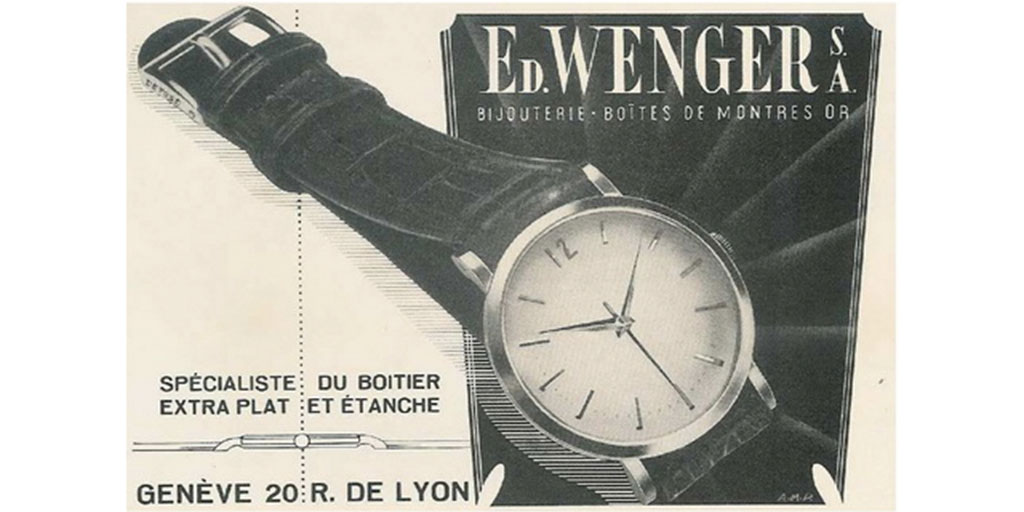

Wenger: Key Number 1

Wenger holds the prestigious place as one of Patek Philippe’s favorite case makers. Because of this, some of the most important watches ever made are cased by Wenger such as the ref. 2499. André and Edouard Wenger started making cases in 1912 and registered the trademark BG Wenger in 1920. They won their first international prize at the 1925 Paris Exhibition. They became the reference for Geneva Art Deco horology making both pocket and wristwatches for the most important watchmakers.

After the Great Depression, the company specialized in steel case manufacturing and pioneered the “acier inoxidable” process. Among their many innovations, it’s worth noting that the first Reverso watch, which was first produced by Patek Philippe, can be credited to Edouard Wenger.

Following the first two years of case production of the ref. 2499 by Emile Vichet, Wenger produced all subsequent series until 1982 when Patek started making its own cases at its subsidiary Ateliers Réunis. It is estimated that Wenger made around 30 yellow gold cases for the first series ref. 2499. Wenger cases for the ref. 2499 are slightly larger at 37.5 mm in diameter than 36 mm for the Vichet cases. Wenger also made steel cases for ref. 130.

The good news is that you don’t have to own a ref. 2499 to experience a Wenger case. Several Calatrava models have distinguished Wenger cases such as refs. 2551, 3433 and 2552 (as shown above).

Wenger also made cases for the often-challenging designs by Gilbert Albert. For e.g., the ‘Futuriste’ ref. 798 (as shown above).

Baumgartner: Key Number and Hammer 2

F. Baumgartner made a range of cases for Patek Philippe from the classic ref. 2526 and early Ellipses to shaped cases for Gilbert Albert and designs inspired by him. The cases for the ref. 2526 were an important design because they housed Patek Philippe’s first self-winding movement – the superlative 12-600AT – together with a twice-baked enamel dial. To begin with in 1953, the first few hundred cases were made with a detachable bezel as a three-piece case. The case became a two-piece with the bezel attached and a screw down back, the very desirable water-resistant back. From the beginning, all ref. 2526 cases sported the distinctive double-P crown design, an immediate differentiation for a classic Calatrava time only design, signifying the important self-winding movement.

In contrast to the elegant and relatively simple case style of the ref. 2526, F. Baumgartner was also a chosen case maker by Gilbert Albert, especially for some of his “Golf” pocket watch references such as the 782, 785 and 799 (shown below).

The below ladies ref. 3442J is a masterpiece in case making. The lugs of this watch are a creation in three dimensions with architectural curves that flow around and embrace the strap. The complex design of the lugs work harmoniously with the geometric dial. This complex design is assumed to be inspired by Gilbert Albert and only a case maker like F. Baumgartner could have taken on such a challenge.

Having proved its skills with shaped watches in the early 1960s, F. Baumgartner also produced some of the very first Ellipses such as the ref. 3546 in 1968 (later Ellipse cases were produced by Favre-Perret Hammer Number 115).

Antoine Gerlach: Key Number 4

Founded in 1871, Antoine Gerlach was a prolific mid-century case maker for Patek Philippe. Starting in 1932, Gerlach had the honor of making the first gold and platinum Calatrava cases for the ref. 96 (see below). The 30.5 mm three-piece case with a snap on case back and bezel remains one of the most distinctive and important watch designs ever.

As with other fine case makers, it made a range of now iconic case designs such as the futuristic ref. 3448 made from 1962 – 1980. Nicknamed the “Padellone Automatic”, “Disco Volante” or “Flying Saucer”, it was the only self-winding, perpetual calendar made by any manufacturer in series (see below).

The company’s brilliance at producing pieces with crisp sharp lines can be seen the spectacular minute repeater, perpetual calendar pocket watch ref. 844 (below):

In contrast to the highly defined and architectural cases, Gerlach also made some of the most organic designs for Gilbert Albert such as the Ricochet pocket and pendant watches refs 788 (see below) and 789.

George Croisier, acquired by J.P. Ecoffey (1950s): Key Number 5

George Croisier was one of the first important, production case makers, starting his business in Geneva in 1870. In addition to making gold cases, Crosier pioneered the creation ‘Staybrite’ steel cases for fine watchmakers. Such an elite skill at making steel watch cases resulted in Croisier making three of the four known steel ref. 1518 (the fourth was made by Wenger). For serious watch collectors, a steel ref. 1518 is a holy grail watch and we all dream of finding a fifth piece, perhaps like the one shown below.

The only known steel ref. 1526 has a case made by George Croisier which was created as a special request for an American Patek Philippe client Briggs Cunningham II in 1949 (see below).

Crosier also made some steel ref. 130 cases – another collector favorite.

François Markowski: Key Number 8

Markowski is a case maker Key Number 8 that we regularly see on Patek Philippe watches and for good reason as the company produced many collectors’ favorite watches for Patek. François Markowski started as an engraver on silver and gold becoming a renowned case maker especially for unusual shaped cases. It is not clear when Markowski started making cases for Patek, but there is a case recorded as early as 1921. Most production for Patek was executed between 1934 until 1963. Markowski is well-known for making many of the rectangular case designs, which were increasingly popular in the post-war years. One of these models was the ref. 1450, or as the collecting community refer to it, the “Top Hat”, due to its unique profile and hooded lugs (see below).

Other wonderful models include the sensuous ref. 2442 nicknamed the “Marilyn Monroe” and the ref. 2441 nicknamed the “Eiffel Tower” which was the inspiration for the 1997 limited edition Pagoda collection to commemorate the opening of the workshops at Plan-Les-Ouates (see below).

Other well-known Markowski cases include: the ref. 425 the “Tegolino” which was launched in 1934 and became a popular collectors’ favorite; ref. 1491 produced from 1940 – 1965 with the distinctive and now sought-after, scrolled lugs; ref. 1593 launched in 1944 and known as the “Hour Glass” a classic, post Art Deco modern design, starting the trend for references such as the 2442 and 2441; ref. 2461 nicknamed the ”Tegola” which in 1950 replaced the smaller ref. 425 and ref. 2468 launched in 1948 and known as the “little sister” to the ref. 1593.

Being the king of shaped case manufacturing, it no surprise that Markowski produced some pieces for Gilbert Albert such collectors favorite the ref. 3424 (shown above).

The rare and short-lived Gilbert Albert asymmetric collection for ladies was made between 1960-61 with Markowski cases for the ref. 3270 (shown above).

Emile Vichet: Key Number 9

Emile Vichet is best known as maker of the legendary ref. 1518 cases and most of the first series ref. 2499, supplying the cases for the first two years of production, making around 10 cases in yellow gold and four in pink. The Emile Vichet ref. 2499 cases feature distinctive lugs, usually described as claw-like, which are elongated and curve sharply downwards. Because of this, Vichet cases have a flat, as opposed to a domed case back, and sit slightly elevated on the the tips of each lug when placed on a table. Vichet’s distinctive lug design was recently paid homage to with Akrivia’s case design for the Chronometre Contemporian II in 2022.

The gold cases for the ref. 1526 (see below), the ‘little brother’ to the 1518, were made by Vichet, as were the ref. 130 cases.

Although Vichet went out of business by the late 1960s, any watch that bears the Vichet key stamp is still a sort after piece such as the ref. 2497 made between 1951 and 1963

A fun fact is that when Patek Philippe’s legendary watchmaker and reguleur André Zibach decided to make a watch as a wedding present for a close friend in 1929, he selected a case made by Emile Vichet. This is a further testament to why many collectors consider a Vichet case as one of the most important manufacturers used by Patek Philippe.

Taubert Frères successor to Frères Borgel (FB): Key Number 11 Hammer Number 11

In 1924, the Taubert family purchased the Borgel manufacture. Francois Borgel was a talented inventor and father of the first waterproof case which he patented in 1892. It’s interesting to note that even when Taubert purchased Borgel they continued to stamp cases with the distinctive and respected FB mark. Also, Taubert cases are a rare example which can be either stamped with key number 11 or hammer 11. This is because Taubert produced cases both in Geneva and La Chaux de Fonds.

For the ref. 96, Taubert only supplied steel cases, as were the cases for the ref. 437. Significantly, in 1935, Taubert made Patek’s first waterproof case ref. 438 with a diagonal screw back in both steel and gold (at 28 mm diameter the refs. 437 and 438 are known as “Boy-size Calatravas” as shown above).

By 1941, Taubert was making Patek’s first waterproof chronograph case ref. 1463 in both steel and gold. Nicknamed the “tasti tondi” the ref. 1463 came out four years after the ref. 130 in 1940. Taubert patented the first waterproof rectangular case for Patek’s refs. 1486 and 1485 (shown above) which were produced between 1940-1953. The ref. 1485 was made only in stainless steel by Taubert using a novel system that was patented in Switzerland. The two-part case is secured by three sliding strips that connect the main case components together in a near lock tight manner. The Swiss patent mark ‘Brevet +’ can be seen on the inside of the case, as well as a ‘+’ on each of the three steel securing strips.

Ref. 2509 with a screw-down waterproof back. Image credit: Collectability

Taubert continued to make screw back cases for Patek for references such as ref. 1563 the split seconds version of ref. 1463; ref. 1591 launched in 1944 as a waterproof perpetual calendar; ref. 2451 known as the “Acuatic” it was the first waterproof Calatrava launched in 1949; refs. 2508 and 2509 launched in 1950 and known as the waterproof “Grand Calatrava” with their 35 mm cases (shown above). By the mid 1950s, there is a slow-down in cases made by Taubert for Patek.

Eggly & Cie: Key Number 23

Eggly & Cie made some interesting cases, especially for the Calatrava collection. One of the best known is the ref. 2407 made between 1945 and 1950 also known as the “Sea Turtle” because of its distinctive profile shape (see below).

Another unusual Calatrava case made by Eggly & Cie is the ref. 1595, a rarely seen reference which is easily recognized by its unusual form lugs. Nicknamed the “Giraffa” by Italian collectors for its long lugs, it is easy to appreciate the resemblance to the neck of a giraffe. It is quite large for a vintage Patek Philippe at 35 mm and wears even larger on the wrist with the prominent lugs. The cases with their long, curved thin lugs were produced between 1944 – 1953 (see below).

In keeping with its reputation for unusual lugs, Eggly & Cie also left their mark on pocket watch cases such as the below ref. 716R which was made for the Peruvian retailer Casa Welsh in 1941.

Atelier Réunis (originally Key Number for Marcel Pugin): Key Number 28

In 1975, Patek Philippe acquired a building on the rue des Vieux-Grenadiers for the workshops of the case, bracelet and chain maker Atelier Réunis, a business owned by Patek but which also supplied other watch manufacturers. In the early 2000s, Patek ceased production for other watch brands and the building became home to the Patek Philippe Museum. Many iconic cases were made in this storied case maker’s workshops such as the ref. 3970, Nautilus and the Calatrava ref. 3919.

One of the most important watch cases to be produced by Atelier Reunis was for the ref. 3970 which was launched in 1986 to replace the ref. 2499. It differed mainly by the arrival of the new Lemania base movement which replaced the Valjoux movement, used by Patek Philippe for more than 50 years. The launch of the ref. 3970 perpetual calendar chronograph in 1986 was a bold move by Philippe Stern. This was the height of the “Quartz Crisis” when many mechanical watchmakers were going out of business. Philippe Stern however, was convinced that mechanical watches, even with complicated movements like the ref. 3970 had a future. Because of this, he entrusted production of the ref. 3970 cases to a manufacturer his family knew well.

Around the same time that the ref. 3970 was launched, Philippe Stern was looking for a classic Patek Philippe time only watch that could be used for international advertising and become recognized as the quintessential Patek Philippe. The Calatrava ref. 3919 with its classic hobnail “Clous de Paris” bezel was launched in 1985 and became the most recognized ‘bankers watch’ of the 1980s and 90s. Again, Philippe Stern decided to keep production of this reference within Atelier Rèunis where he could best monitor quality.

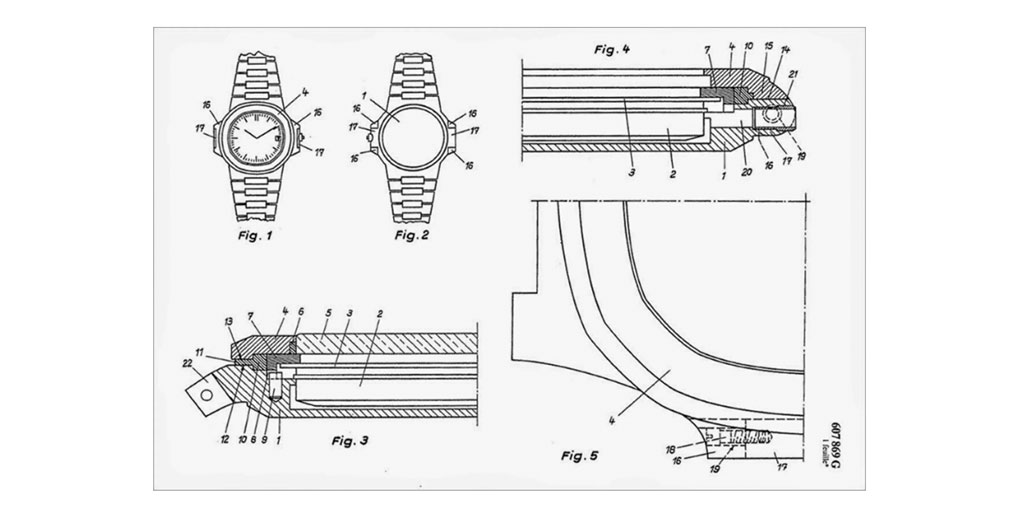

The story of the Nautilus has been documented extensively over the past five years as interest in this steel sports watch reached fever pitch. What is not so well documented is the story behing its case production, starting with the ref. 3700 “Jumbo” Nautilus which was produced from 1976 to 1998 with may variations. When launched it was advertised as the most expensive steel watch on the market. Little did Patek know how such a statement would still ring true over 45 years later when Nautilus ‘mania’ led to record breaking prices for the model. Production of the Nautilus case and bracelet was an important and complicated undertaking for Patek as it had never produced such as robust, truly waterproof sports watch before. Jean-Pierre Frattini was given the job of taking Gerald Genta’s technical drawings and constructing a working prototype. According to Frattini, the original production plan was to have Gay Frères produce the case with integrated bracelet. Unfortunately, Gay Frères shut down soon after the prototype was made and Patek Philippe’s trusted case maker Ateliers Réunis would step-up and start production of what would become one of the most sought after watches in the world.

It’s worth noting that Thierry Stern, now president of Patek Philippe, started his career at Ateliers Reunis where he learnt the art of case, bracelet and jewelry making and what differentiated Patek from any other watchmaker in terms of production and passion for excellence.

Favre-Perret: Hammer Number 115 Case maker mark FP

Favre-Perret had the distinct honor of producing the cases for the ref. 3940 from 1985 until 2003 when the company was brought by the Swatch Group (the Hammer Mark then changed to 357). The final four years of ref. 3940 case production was by Calame which had been acquired by Patek Philippe in 2001 and changed its case stamp to PPCo.

In addition to the Nautilus cases made at Atelier Rèunis, Favre-Perret also made some of Nautilus ref. 3700 cases in their workshops in La Chaux-de-Fonds, and would also supply case parts to Atelier Rèunis to help with production volume. The unique Nautellipse ref. 3770, a combination of the Nautilus and Ellipse was made at Favre-Perret during its run from 1980 – 1990.

Given that Favre-Perret made the Nautellipse, its perhaps not surprising to learn that it also made more unusual Ellipse cases such as the ref. 3634/2G as well as the more traditional ref. 3848.

Guillod & Cie Guillod Gunther: Hammer Number 121

Guillod & Cie started making cases in 1866, gradually shortening its name to Guillod and specialized in gold cases. It is registered as a company in La Chaux-de-fonds under both names: Guillod or Guillod & Cie. In 1934 it became identified with the master case maker number 121 within a hammer which was the key mark for La Chaux-de-fonds. After the quartz crisis in the 1970s, the company merged with another La Chaux-de-fonds case maker Gunther & Cie, becoming Guillod Gunther SA.

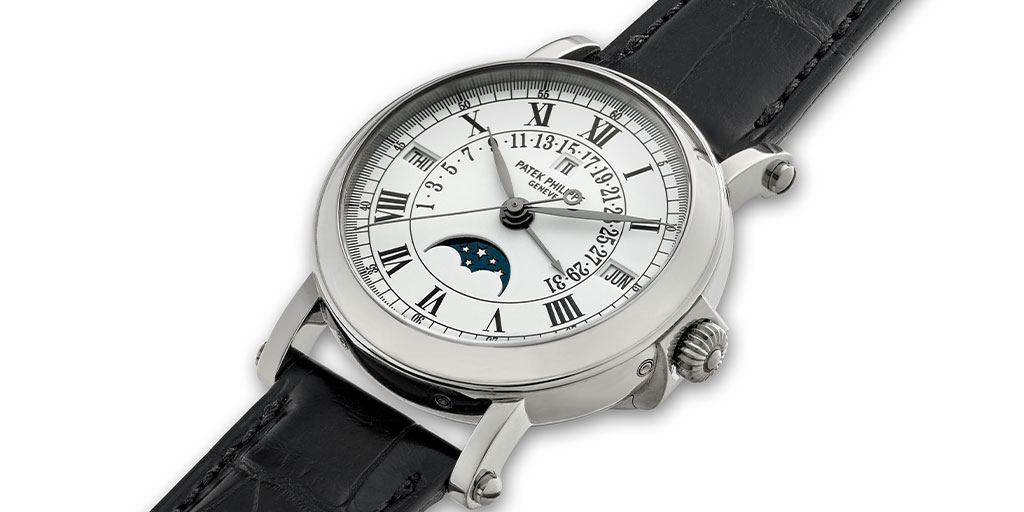

During the 1990s and 2000s, Guillod made a range of cases for Patek Philippe from the ref. 4820 ladies Calatrava launched in 1989 and produced until 2002; the ladies Calatrava ref. 5006; the distinctive Officer’s case of ref. 5059 self-winding perpetual calendar made between 1998 – 2006; to the the great classic split seconds chronograph ref. 5004 produced between 1994 and 2009 with a case similar to the ref. 3970.

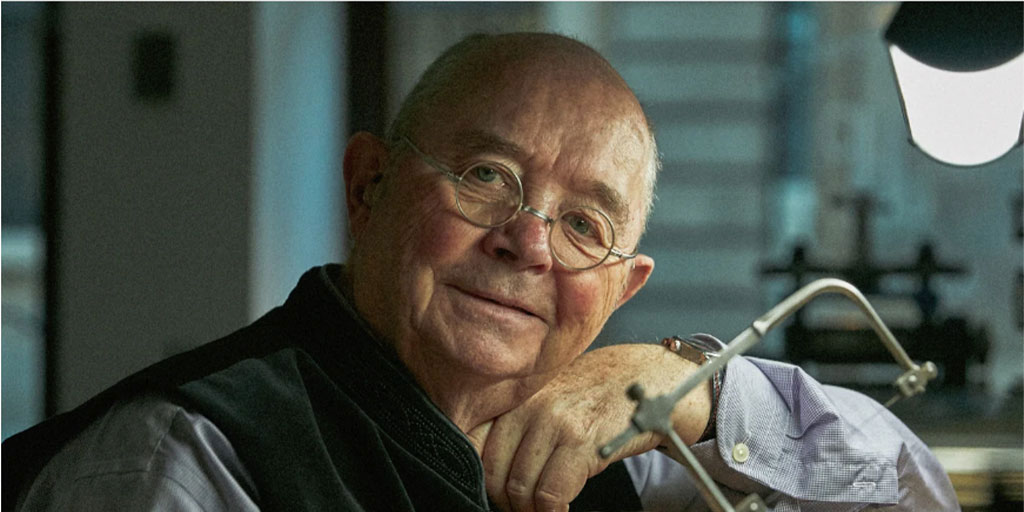

Jean-Pierre Hagmann: Case maker mark JHP

Within the annals of case-making, there is one individual, or boîtier who stands above all others: Jean-Pierre Hagmann. Born in Geneva in 1940, JP Hagmann is one of the most legendary case designers and deserves special attention.

He began his professional career as a goldsmith at Ponti Gennari in 1975 (Ponti Gennari made many exceptional bracelets for Patek Philippe). He moved to Gay Frères in 1961 where he started adjusting gold bracelets for the finest manufacturers including Patek Philippe. From 1963 he worked with G. Brera and quickly gained a reputation as a highly skilled technician. In 1971, he joined J.P. Ecoffey (JPE) renown chain and bracelet maker. He quickly became the director and by the time Ecoffey brought the case maker George Croisier one of Geneva’s most renown and specialized case maker, Hagmann was placed in charge. It was at this point that Hagmann focused on mastering case making and in 1984, he established his own company with the case maker mark JHP. Today, JP Hagmann remains the point of reference for case making and is the most skilled artisan still working. For Patek Philippe, he has been entrusted with making all the cases for minute repeaters, namely, references 3974, 3979 and 5029.

He is credited for making the legendary Star Caliber cases in both gold and platinum for which he produced a total of 26 cases – with only one returned for adjustment – an achievement he remains particularly proud of.

A Patek Philippe minute repeater stamped JHP is an additional trophy for collectors. So why are his cases so sought-after? Mr. Hagmann believes that smaller and lighter cases produce a better sound for minute repeaters, with gold being a superior metal to denser platinum. He singles out rose gold as the best metal for a repeater case because the composition of the material makes it stiffer than other gold alloys. He believes that a repeater watch case should be no thicker than 0.5 mm on each side of the movement and the crystal should be domed. One of his important case innovations is the recessed track on the side of the watch case for the repeater slide, a development that is now industry norm. Historically, the slide was mounted in the surface of the case side, attached on the inside with a screw which according to Hagmann meant occasional instability and off-center alignment.

A review of Patek Philippe case makers needs to include recognition of a stamp that is on its all its precious metal cases. In 1881, the Swiss gold hallmark denoting 0,750/18K gold or platinum featured a lady’s head representing Helvetia. Numerous versions of the Helvetia head appeared on pocket watches and wristwatches over its almost 115 year reign. In August 1995, the official Swiss stamp image for precious metals changed from Helvetia’s head to the much-loved St Bernard dog image whose lovable image has remained consistent over the years of modern watch making.

The above selection of case makers represents the case makers most regularly used by Patek Philippe, particularly from 1934 (when the key numbers were introduced) to the early 2000s (when Patek took most of its case production in-house) but it is by no means a definitive list (other case makers include for example include Marcel Pugent, Guyot, Weber). Some of the great jewelers such as Ponti Gennari (Key Number 26) and Gay Frères (Key Number 32) made cases for specific Patek Philippe bracelet watches, but these were the exception rather than the rule. In addition, there are always outlier case makers who worked for Patek Philippe but cannot be simply identified by a number in a key or hammer head. For example, the celebrated master case maker Jean Vallon specialized in anti-magnetic and water-resistant cases in La Chaux-de-Fonds. His work can be identified by a fish/narwhal stamp and can be seen for example on an Amagnetic ref. 3417A. The craftspeople and companies that worked with Patek Philippe are endless and each should be recognized for their important contributions. So if you come across an unusual case marking, let us know, it’s always a pleasure to learn about new craftspeople.

We would like to thank Tortella & Sons for their support with the research on this article.

March, 2023