Patek Philippe is one of the only large-scale watch manufacturers in Geneva to produce as much of its own movements as is possible. This was not always the case. Some of the most important watches ever made by Patek started their lives in another watch movement atelier. This new Collectability series will reveal which watch makers reigned supreme as makers of primary movements or ébauches from where Patek Philippe could put its own indelible mark. Certain names such as Victorin Piguet, Valjoux, Golay and Lemania are well known in the Patek catalog of vintage timepieces, but the story behind them is not so well known. Today, we will learn about the legendary Victorin Piguet best known for making early chronograph, minute repeater and perpetual calendar ébauches for Patek Philippe, and was also instrumental to the company’s development and manufacturing of some of the most important timepieces ever made.

The relationship between a master watchmaker like Patek and an ébauche maker like Victorin Piguet was completely normal throughout most of the watch industry’s history. Still today, most brands buy ébauches or movement blanks and then finish in-house. It is important to note, that although ébauche makers would deliver unfinished movement blanks, Patek Philippe’s watch makers would then modify, assemble, decorate, and finish to its own, unique standard. Victorin Piguet enjoyed a special relationship with Patek Philippe because it partnered on particularly complicated movements. It is this trust and mutual respect that resulted in legendary timepieces like the Graves Supercomplication.

History

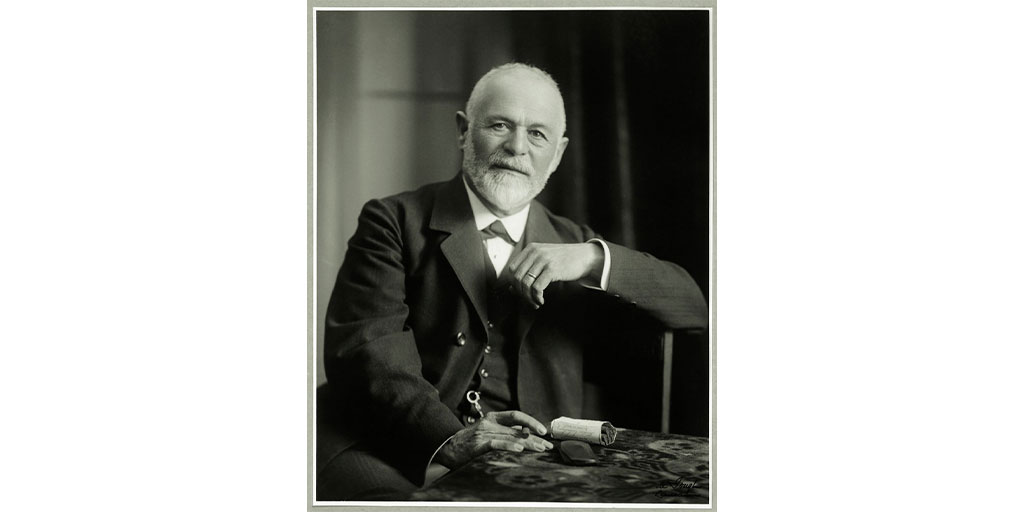

Victorin Piguet (1850 – 1937) was born in Le Chenit a village in the Vallée de Joux, son of watchmaker Daniel Henri Piguet and his second spouse, Louise Françoise LeCoultre. With watchmaking in his genes, the young Victorin quickly started to learn his craft and by the time he was in his twenties was a master teacher at the school of watchmaking in Geneva. In 1880, he founded Victorin Piguet et Frères with his brother Alfred, who was also a watchmaker, and by 1883, he moved his business back to Le Sentier in his native Vallée de Joux. In 1920, Victorin turned his company over to his sons, Jean-Victorin and Paul Piguet. Victorin Émile Piguet died in 1937 and later, after Jean-Victorin Piguet’s death his son Henri-Daniel took up the helm of the family business. Les fils de V. Piguet continued to work for other renowned brands such as Audemars Piguet and Vacheron Constantin.

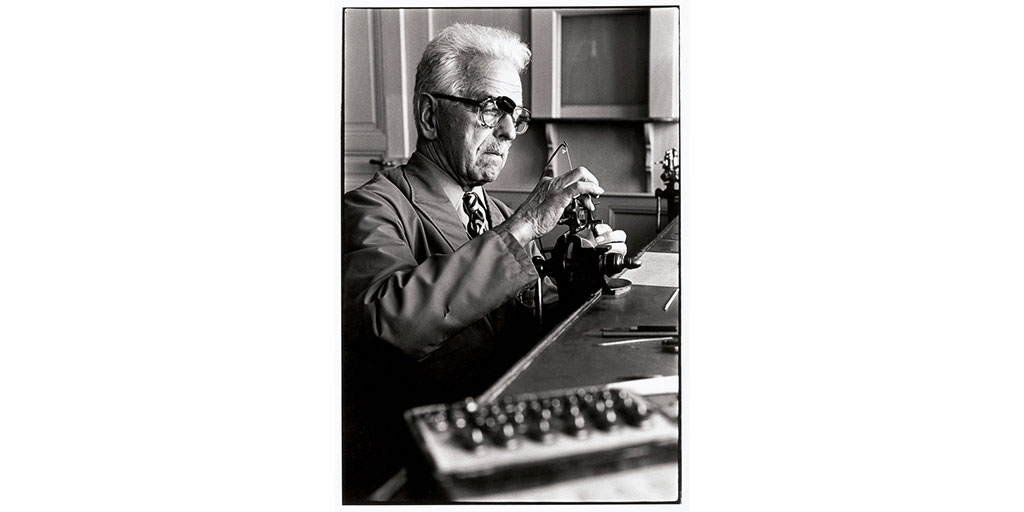

The house of Victorin Piguet maintained a historic and critical relationship with Patek Philippe for many decades. In 1980, Patek Philippe president Henri Stern attended the centenary celebrations of the company as guest of honor. At this time, the company was run by Victorin’s 76-year-old-grandson, Henri-Daniel Piguet and it’s fair to say that the company was virtually a subsidiary of Patek Philippe as its three watchmakers worked exclusively on Patek’s grand complications, especially perpetual calendars, minute repeaters and astronomical functions. This relationship helped preserve the craft of the cabinotiers, traditional watch makers located in the Swiss countryside of Vallée de Joux who were ready to take on the challenge of creating any type of complication by using their exceptional skills honed over generations.

From the launch of the company in 1880, Patek Philippe was one of Victorin Piguet’s first clients producing primarily minute repeater and chronograph ébauches for pocket watches destined for Patek’s most important clientele such as members of Europe’s and Asia’s royal families and even the Pope. A stroll around the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva is evidence of this with many of the most breathtaking, complicated pocket watches credited with a Victorin Piguet & Cie ébauche. Interestingly, there are pieces in the Patek museum with Piguet Frères ébauche movements from the 1870s as Victorin and his brother Alfred were already establishing themselves as young genuius movement makers before the official creation of their company. As we will learn later, the Piguet family name was already associated with Patek as early as 1841 when it started producing the first minute repeater ébauches for pocket watches.

Chronographs and split-seconds chronographs

Innovations started to come early to Victorin Piguet’s catalog. One of the first complications that they mastered around 1880 was to produce new ébauches for split-seconds chronograph watches. Patek had been producing chronograph pocket watches since 1870, but his was an exciting new movement that Patek was keen to introduce as demand was growing among the company’s elite clients to time their horses, and later, motor cars. Victorin Piguet first constructed ébauches with a half plate or a three-quarter plate (circa 1880), then with a quarter plate (1890–1920). In this type of construction, the split-seconds mechanism is placed on the dial side of the base plate. The off-set center wheel allows the chronograph’s wheels and pinions and its split-seconds mechanism – and their hands – to function via the movement’s center. This caliber, whose layout and finishing evolved over time, was used well into the 1920s for watches with or without minute registers, as well as for watches with additional horological complications (such as repeating and/or perpetual calendar).

In 1902, Patek received a patent for the first pocket watch with a double chronograph using a Victorin Piguet 19 lignes ébauche. A double chronograph differs from the split-seconds chronograph in that, after the second hand is stopped, a second depression of the pusher will return that hand to zero instead of bringing it back to its position above the first hand. Therefore, the durations of various events, or phases of an event, may be individually measured.

After the First World War, it did not take long for clients to request chronograph wristwatches. Thanks in part to the genius ébauches made by Victorin Piguet, Patek was already a respected chronograph maker as it remains today. The first Patek Philippe wrist chronograph was made in 1924 with a 13 ligne Victorin Piguet ébauche; a total of three were made. Until the introduction of the ref. 130 and the first chronograph produced in series, Victorin Piguet made many different wrist chronographs which were usually special orders for important clients as the high cost of these complicated pieces was already a factor. It’s worth noting that before Valjoux started producing the ébauche for the caliber 13-130 found in the ref. 130 and later chronographs until the Lemania base for the caliber CH27-70, it was the Piguet 13 ligne chronograph ébauche that was found in most wrist chronographs made in the 1920s/30s and the first ref. 130s (1927 -1934).

But let’s not forget wrist split seconds chronographs. What may surprise some readers is that the first wristwatch with a split-seconds chronograph was made in 1923, a year before the first chronograph wristwatch. Not surprisingly, it contained a 12 ligne extra-flat Victorin Piguet ébauche. This movement went on to inspire the extra-flat split seconds chronograph ref. 5959P with caliber CH R 27-525 PS launched at Basel 2005. The owner of the first 1923 version was Attilio Ubertalli who had been president of the Juventus Turin Soccer club, presumably liked to keep an eye on the timing of the beautiful game.

Minute repeaters

From the birth of the company in 1839, Patek Philippe was making minute repeater pocket watches. One of the earliest in the museum (above) is a quarter repeating pocket watch made in 1841 with an ébauche made by ‘D.H. Piguet’ – which we assume was Victorin’s father, Daniel-Henri Piguet who introduced his sons to Antoine Patek and the rest is history. The Piguet brothers produced many minute repeater ébauches, but an innovation they excelled at was miniaturizing the complicated minute repeater ébauches to fit into a delicate ladies’ pendant piece.

One of the earliest known 12 ligne pendant minute repeaters was made in 1883 with a Victorin Piguet & fils ebauche (above). Between 1839 – 1926, for repeaters activated by depressing a push piece on the winding crown, Patek Philippe used three different ebauches: 17 ligne open faced, made by Victorin Piguet & Co.; 18 ligne hunter case made by Victorin Piguet & Co. and a 19 ligne open-face made by J. Aubert.

The first minute repeater wristwatch was made in 1916 for a lady with a tiny 10 ligne Victorin Piguet ébauche (above). It is most likely that this movement started out for a pendant watch and was later presented as a wristwatch for a special commission. Victorin Piguet went on to make ébauches for minute repeater wristwatches made in limited quantities until the 1960s when production slowed down almost completely. This was in part because of the high price of these pieces and that they had become out of fashion.

Very rarely were early minute repeater wristwatches made with additional complications. The first known piece was completed in 1939 with a perpetual calendar and moon-phase (above). Incredibly, it was not until Philippe Stern commissioned the ref. 3615 in 1982 using a Victorin Piguet movement blank from the company’s old inventory, that the first wristwatch with a minute repeater, perpetual calendar and chronograph was made (see below).

Perpetual calendars

From the 1890s, Victorin Piguet started to make ébauches for Patek’s exceptional perpetual calendars, many of which went on to win Geneva Astronomical Observatory competitions. For example, in 1906-1907 a perpetual calendar made in 1890 with a Victorin Piguet ébauche, was adjusted by one of the great regleurs, C. Batifolier and received a much-coveted first place Bulletin de Première Classe.

Many collectors regard the ref. 725 as the essence of a Patek Philippe perpetual calendar. In fact, the entire lineage of the references 1518, 2499, 3970, 5970 and 5270 can be traced back to the ref. 725. It was made with a caliber 17-170 perpetual calendar by Victorin Piguet & Cie (interestingly, this is the same base caliber as in the World Time ref. 605HU). The ref. 725 is a true instantaneous perpetual calendar with the date at 3 o’clock, the day of the week at 9 o’clock, the month at 12 o’clock, and moon phases with aperture at 6 o’clock. The movement is adjusted to 8 positions and the quality of movement finish is second to none.

With its magnificent perpetual calendar ébauches, it it not surprising that a Victorin Piguet base movement made another first, the first known perpetual calendar wristwatch. Its movement, recorded in the company archives was partially manufactured in 1899, possibly for a pendant watch, but it was never used before its completion in 1925 for the watch shown above.

Grand complications

Grand complication watches are among the most extraordinary achievements in horology. They must possess at least three complications: astronomical functions (calendar, moon phases), striking (minute repeater) and the division of time (split-seconds chronograph). Patek Philippe started to make Grand complications in 1895. One of the first was a Grand Complication pocket watch with minute repeater, split-seconds chronograph and perpetual calendar which completed between 1895 – 1897 using a 19 ligne Victorin and Piguet ébauche. All the Grand Complication pocket watches in the Patek Philippe Museum which were produced from 1895 until the 1970s contain either 16, 17, 18 or 19 lignes ébauches by Victorin and Piguet.

It is not surprising that when Henry Graves Jr. commissioned Patek Philippe to make the world’s most complicated timepiece, Victorin Piguet & Co. were immediately partnered with having worked on most of the company’s grand complications to date. The making of the Graves Supercomplication was one of the greatest achievements in watchmaking requiring over five years of work before its completion on September 28, 1932 (it was delivered to Henry Graves in January 1933). Many extraordinary craftspeople both inside and outside of Patek Philippe worked on its creation. However, almost all the manufacturing work took place in Le Sentier at the Victorin Piguet workshop by three generations. Here, under the expert eye of Victorin himself, the world’s most complicated timepiece was assembled. Victorin’s sons Jean and Paul worked on the movement and assembly and even grandson Henri-Daniel Piguet made an important and noted contribution by developing the novel hand-setting mechanism.

Other Innovations

The Piguet brothers were keen to work with Patek to master new complications and this symbiotic relationship resulted in many patents. For example, the earliest known independent seconds pocket watch by Patek with a Victorin Piguet ébauche was made between 1888-1889 and patented on May 23, 1889 (above). Jean Adrien Philippe even purchased a similar pocket watch for himself on January 31, 1894, as he was so impressed with this new movement. In 1892, Victorin Piguet created a ébauche for one of the earliest two-time zone pocket watches with day date (Patek Philippe Museum Inv. P-1268); a three-time zone came in 1900 (Patek Philippe Museum Inv. P-1373), plus a patented center seconds with two-time zones also in 1900 (Patek Philippe Musuem Inv. 892).

We take an independent seconds hand for granted as something of a basic movement addition, but as we saw above, it was not until 1889, that an ingenious Victorin Piguet ébauche enabled this addition. This movement would later play an important role in the future of Patek Philippe. In 1933, Patek decided to make a bold move: the aim of which was the capability to “manufacture all our movements in our own ateliers.” To help them achieve this, the company appointed Jean Pfister as technical director. Pfister soon realized that the company’s first in-house movement needed to be a workhorse that could be used in various time only, wristwatch models, starting with the ref. 96, the first official Calatrava to be produced in series. During the early 1930s, wristwatch sales were outnumbering pocket watches by two to one, so it was time for the company to focus on a wristwatch and a new movement for the modern era. The caliber 12”’ 120 was this manual movement with an off-set seconds hand. In order to modify the movement to include a center seconds mechanism, Patek called upon its trusted partner. Victorin Piguet & Co. who ingeniously designed a notably elaborate set-up that included a pivoted lever to support an intermediate wheel. Its worth noting that while Victorin Piguet was modifying a relatively simple movement, it had just completed the world’s most complicated timepiece for Henry Graves.

Victorin Piguet & Co. contribution to Patek Philippe’s catalog of horological innovations cannot be underestimated. It was a genuine partnership that resulted in extraordinary timepieces and many historical firsts. This article focused on some of the best-known innovations and complications that Victorin Piguet contributed to, but is by no means a complete list for example, pocket and deck chronometers, early jump hours and power reserve mechanisms are a few additional innovations that deserve recognition. No other ébauche maker working with Patek Philippe could be credited with so many “firsts” which is testament itself to the importance of this maker in the annals of watchmaking.

March 2023