When a World Time Patek Philippe wristwatch ref. 2523 or 1415 comes up for auction, the watch world stops to observe the sale of one of the most coveted watches ever made. Why does one of these watches which tells the time in all 24 time zones cause such international interest? The answer is simple, each reference contains an ingenious movement made by Louis Cottier.

Louis Vincent Cottier was born in Carouge, Switzerland in 1894, the son of a watchmaker and inventor, Emmanuel Cottier. In 1885, Emmanuel invented a World Time system which he presented to the Société des Arts. Following in his father’s footsteps, Louis became a watchmaker after attending Geneva’s horological school where he distinguished himself as a talented watchmaker receiving several prizes, including two from Patek Philippe. After graduating, he worked for a couple of watchmakers including Jaeger’s Geneva workshop until he opened his own workshop in the back room of his wife’s book and stationary store in his hometown of Carouge. He manufactured fine desk clocks, pocket watches, wristwatches, and various prototypes. By 1931, he had perfected his World Time mechanism, inspired by his father’s earlier version. He first offered his invention in the form of a pocket watch to then renown French jeweler Baszanger. However, watchmakers such as Patek Philippe, Rolex and Vacheron Constantin immediately took interest and Cottier started to create many different versions of his movement for both pocket and wristwatches. Some of his most important, patented movements were made specifically for Patek Philippe. In 1947, with his business growing, Louis Cottier moved to 20 rue Ancienne, Carouge. In addition to being a talented painter and draughtsman, Louis Cottier was also a historian of his beloved city of Carouge, where he lived all his life. Following his death in 1966, his workshop, transferred to the Musée de l’horlogerie et de l’émaillerie de Genève, and is now part of the collection of the Geneva Musée d’art et d’histoire. As a final honor to one of its most famous citizens, Carouge named a square after him, a fitting tribute to a modest and humble man who changed the world of watchmaking.

The need to tell the time accurately in all 24-hour time zones is a relatively recent invention within the annals of timekeeping history. It was not until the advent of the railroad in the 1800s that there was a need to divide the world into time zones, also known as standard time. Standard time is a human construction which asserts that the time kept across a geographical area is uniform – even though according to the sun it is not. Britain, who led the world in railroad and electric telegraph technology, was the first to adopt standard time in the 1840s. In the USA however, by the 1880s there were some 49 different “official times” kept across the US railroad network, leading to great confusion for travelers and railroad administrators. The solution, developed by Charles Dowd in 1870 was to divide the whole country into different time zones. This new system which standardized “railroad time”, went live on November 18, 1883. American citizens, just like Britain’s population had decades earlier, had their lives disconnected from the sun’s and began living their life according to a machine – standard time. The next step was universal time, and this was determined at the International Meridian Conference in Washington D.C. On October 1, 1884, 41 delegates from 25 countries conducted three weeks of negotiations which resulted in Greenwich becoming the prime meridian of the world and Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) the world’s universal time. Today, GMT has given way to the coordinated time of four hundred highly precise cesium atomic clocks known as Coordinated Universal Time or UTC.

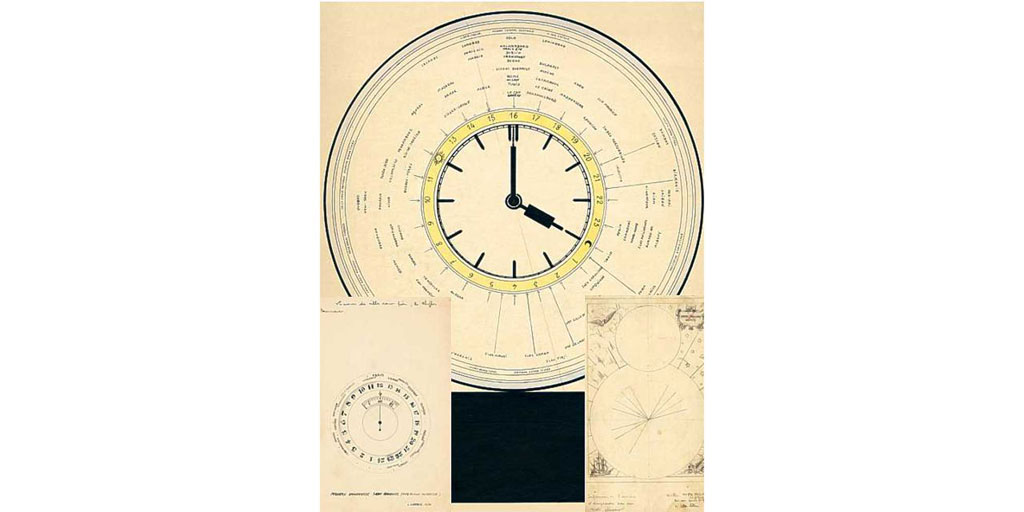

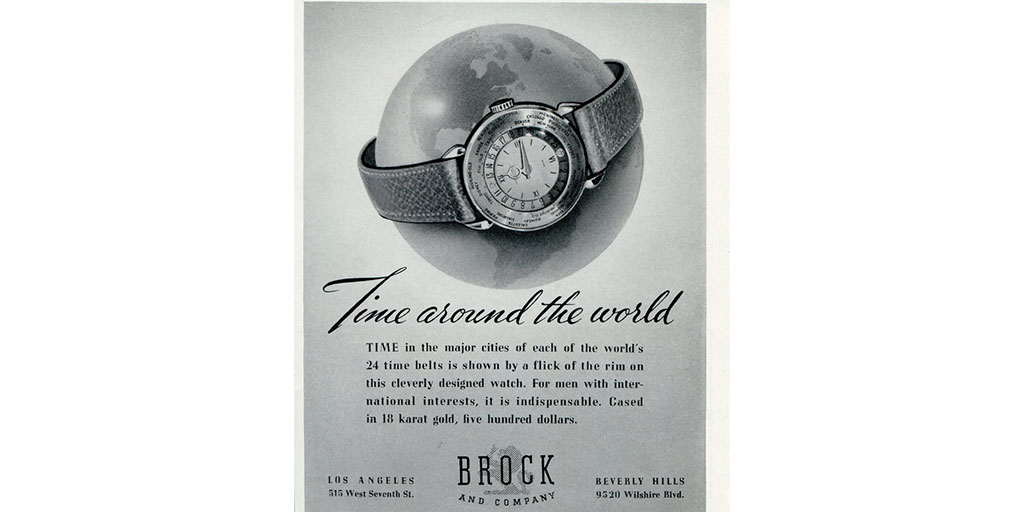

Although the world was happily existing within a 24-hour time zone for many decades, it was not until Cottier’s brilliant invention in 1931 which clearly indicated all time zones on the dial of a watch that the watchmakers could offer travelers an easy way to tell the time around the globe. Cottier’s genius lies in his design which legibly displays real time in cities or islands distributed over our planet’s 24 time zones. Even in today’s World Time watches, the basic principle of Cottier’s design remains the same. City names circle the periphery of the dial above an inner 24-hour ring that turns counterclockwise. The ring’s movement simultaneously coordinates the times in all time zones, while the hands indicate the time in the place whose name is displayed at 12 o’clock, which is considered local time.

Cottier continued to refine his movements and from 1937 until 1965, Louis Cottier delivered around 380 movements to Patek Philippe, mostly World Time (caliber HU for “Heures Universelles”) but also travel time, automatons, and linear or digital display feature watches.

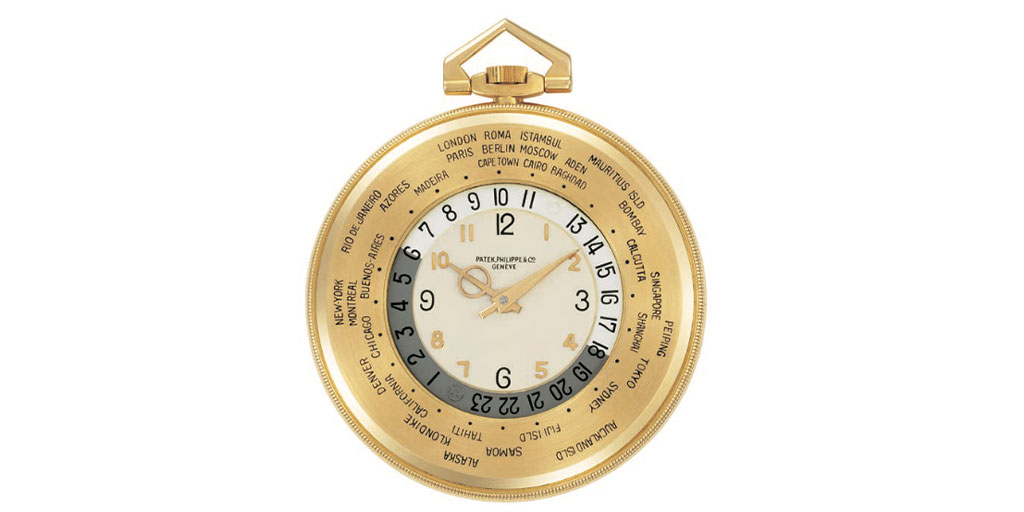

Patek’s relationship with Louis Cottier started in 1936 when he developed the first ref. 605 HU pocket watch as a pre-production model for Walser, Wald & Co., Patek Philippe’s agent in Argentina (see above). Delivered on November 13, 1937, this earliest known World Time pocket watch is now in the Patek Philippe Museum. Between 1937 and 1964 Cottier delivered around a hundred ref. 605 HU pocket watches, mostly in yellow and rose gold. At the beginning, dials were either silver, champagne or pink.

Around the mid 1940s, ref. 605 HU DE (Décor Email) with cloisonné email inner dials started to appear as an alternative with different world map decorations depending on the retailer’s location, but usually with a depiction of the Americas, Europe or Asia. Other, rarer decorations include a world map, compass, zodiac signs and mythical images such as Neptune (above) and a ‘Star Dragon’.

Ref. 605 HU pocket watches from the 1940s and 1950s without a cloisonné center dial represent some of the best value options for collectors. Cottier himself would work closely with Stern Frères on the production of his World Time dials and some depict evidence of his personal whimsy with a face engraved into the moon symbol or unusual, hand-cut hands (see above).

From the beginning of his relationship with Patek Philippe, Cottier was also making World Time wristwatches. 1937 was a busy year for Cottier and Patek’s watchmakers as three World Time wristwatches were produced: the ref. 96 HU, ref. 515 HU and ref. 542 HU. The ref. 96 HU (above) which can be seen in the Patek Philippe Museum is an interesting piece as it was probably a prototype to ‘test’ Cottier’s World Time movement adjustment. The watch, which came up for auction at Christie’s in 2011, has a 12”’ movement that was made in 1913 and modified to incorporate Cottier’s World Time mechanism in 1937. In this first-known wristwatch version, the user can rotate the inner dials, but not the outer bezel with 28 cities. It’s worth noting that this milestone watch in the history of the World Time does not have Patek Philippe’s signature on the dial.

The second World Time wristwatch to be completed in 1937 is ref. 515 HU in an elegant, rectangular rose gold case which can also be seen in the Patek Philippe Museum (above). Like the ref. 96 HU, it has a fixed, outer time zone plate showing 28 locations and a 24-hour rotating disc. This timepiece was made for a client in New York who may have lived overseas as it is calibrated for the Greenwich time zone. The dial was designed by Cottier and made by Stern Frères. It is believed that only three ref. 515 HU watches were ever produced.

The third watch to be produced in 1937 is the ref. 542 HU (above). Based on a 10”’ Lecoultre movement, it is the smallest World Time produced by Patek. The three-piece case was made by Wenger with “Brancard” shaped lugs, and the bezel engraving, and dial enameling was made by Stern Frères. It has a 24-hour rotating disc and shows 30 place names on the broad rotating bezel. It is believed that three ref. 542 HU watches were made. The watch above is in the Patek Philippe Museum.

Between 1939 and 1948 the ref. 1415 was produced in a total of three dial series. The first series has black enamel indexes and Roman numerals; the second series features black enamel indexes and gold applied numerals; the third series has gold applied indexes and Roman numerals often with a cloisonné enamel inner dial. The only known platinum version of the ref. 1415 was unveiled by Patek Philippe in 1939. In 2002, this wristwatch made headline news selling for a then astronomical CHF 6.6 million, around USD 4 million – the most ever paid for any wristwatch. Should it come up for auction today, another world record would no doubt be made. It is thought that only around 82 ref. 1415s were made, only 20 of which were decorated with enamel cloisonné center dials. The number of time zone locations depicted on the outer dial would depend on the market destination and time of production starting with 28 cities in 1939 up to 42 cities in the 1950s. All dials were made by Stern Frères. The 31 mm cases of the ref. 1415 were made by Wenger (Key Number 1).

Simultaneously, during the early production of ref. 1415, approximately three examples, in yellow gold of the ref. 1416 were made. The difference between the two models can be seen with the unusual and rare “bean-shaped” lugs of the ref. 1416.

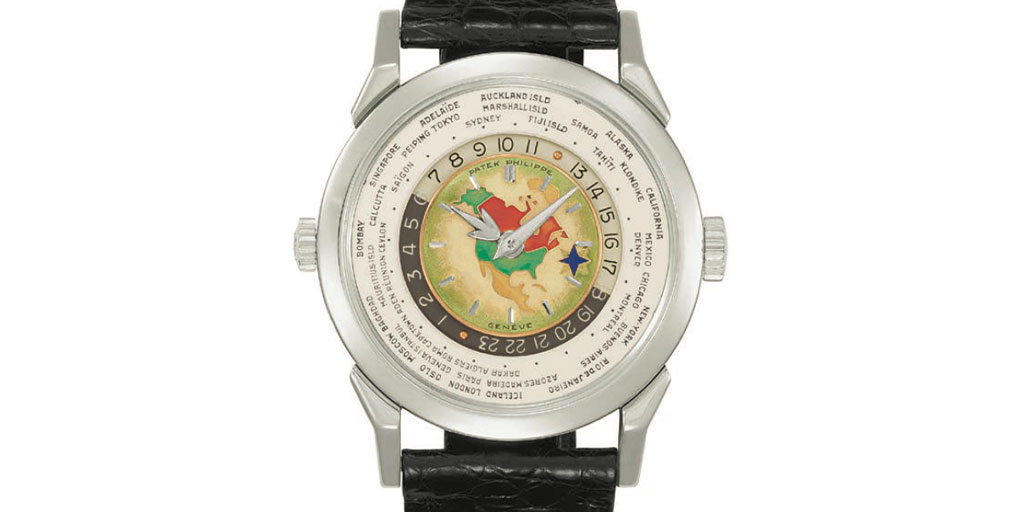

The World Time wristwatch that really makes collector’s hearts flutter is the ref. 2523. Launched in 1954 to replace the ref. 1415, the ref. 2523 was the first World Time with two crowns. The second crown at 9:00 o’clock sets the local time via a rotating disc. In 1953, Cottier invented this new two crown system regarded by many as one of the most practical innovations of 20th century watchmaking. In addition to a greater security and precision in the choice and maintenance of the city of reference, it offered greater protection against shock and wear on the bezel bearing the city names. During the production of the ref. 2523, the ability to print the city names rather than engrave them, resulted in even greater legibility. To produce this masterpiece, Cottier modified Patek Philippe caliber 12-400 movements, which then became 12-400 HU. It is believed that during the production of the ref. 2523, from 1954 to the mid 1960s, Cottier delivered around 45 modified 12-400 HU movements. The first 25 movements were cased in yellow, rose, and white gold by A. Gerlach (Geneva Key Number 4). Only one version is known to exist in white gold (see below). All the dials were made by Stern Frères.

Versions with the various, much sort-after enamel cloisonné centers were decorated by enamelers Nelly Richard or Marguerit Koch who both worked exclusively for Stern Frères and also decorated the enamel versions of the ref. 1415. A few ref. 2523 were made with metal center dials. Rarer still are versions with a plain blue enamel center dial such as the 1953 pink gold ref. 2523 with a Gobbi signature that sold for an astonishing USD 9 million in 2019 at Christie’s Hong Kong. Around 20 versions of the ref. 2523/1 were made between 1953 and 1973, these only had metal center dials. The lugs shape and size slightly differed from the ref. 2523. The case size for both ref. 2523 versions was 35.5 mm.

Louis Cottier’s love of clocks was not neglected, and he made a few World Time pieces for Patek Philippe that rarely come up for sale but cause a stir when they do. The Patek Philippe Museum has a two very different World Time clocks. A magnificent brass table clock set on a marble plinth made circa 1940 depicts 67 time zones on the fixed dial, with passing strike of the quarter hour with quarter repeating on two gongs.

The other clock is a delightful ref. 828 HU made in 1952. Made from yellow gold, silver and enamel, the cloisonne enamel depicts the northern hemisphere as seen from Mexico. Smoke coming from a factory flue indicates the city of Cananea; a canoe, a fish, a mountain and a pyramid are depicted in white cloisonné enamel, the octagonal base has eight balls for ‘legs’. The cloisonné dial depicts Mexico, southern USA and northern Guatemala. A red dot denoting Mexico City makes us assume this was a special piece made for a client from the region. The gold hands are made by Cottier and he transformed a caliber 21”’ with an eight-day barrel to make the World Time movement.

Each dial of the World time, viewed in succession is like a snapshot of the world’s geopolitical history. For example, on the first wristwatch model ref. 1415 introduced in 1939, three cities represented Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) – London, Paris, and Algiers, while GMT +1 time zone featured Oslo, Geneva, and Rome. The reason for this is that prior to World War II, Paris and London shared the same time zone. This made sense because the solar time for Paris, to the east, is only nine minutes ahead of the Greenwich median, while parts of France is to the west of it. However, from 1940, as in the period of 1914-1918, German time was imposed on occupied territories. Such divisions remain the same today as Central European Time. Another historical indicator is the changing names of capital cities. For example, World Time watches made from the late 1930s to the 1950s would use an array of names for China’s capital — Pékin, Peiping, Nanking, Beijing. Ironically, this changing geopolitical landscape is also a good way to authenticate a World Time for example, if a watch supposedly dates from 1945, but has Beijing on the dial, there is an issue.

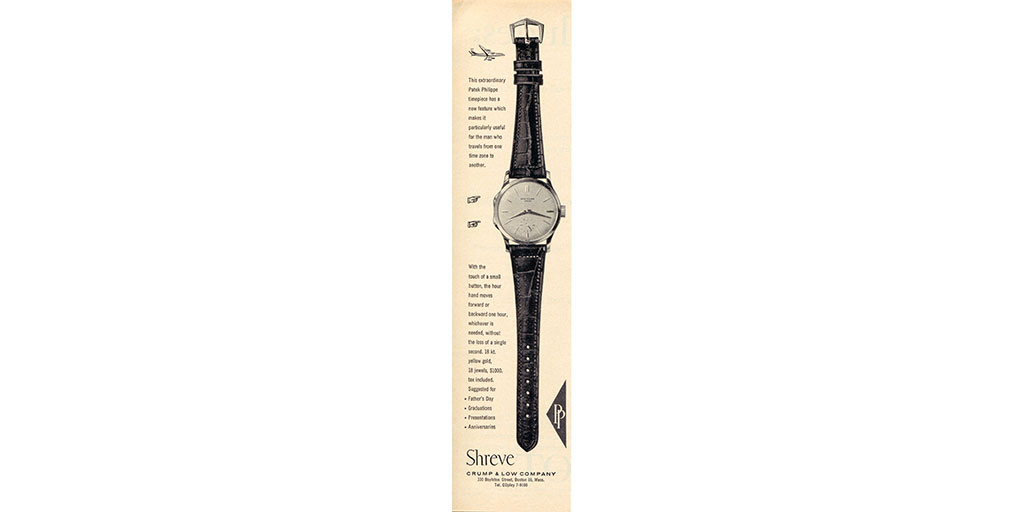

In the 1950s, Louis Cottier developed several other novelties for Patek Philippe. One of his most notable was the celebrated “dual time” movement. His invention solved the problem of synchronizing the minute hand, a problem which existed in twin movement watches by other manufacturers. Cottier’s Two-Time Zone movement with two or three hands, developed in collaboration with Patek Philippe’s specialists, is amongst his most successful inventions. Finished in 1957, the prototype was patented by Patek in 1959 (no. 340191).

These wristwatches, references 2597 and 2597 HS, went into production in 1958. The first version to be launched, ref. 2597 had only an hour hand, which was independently adjustable by two pushers: depressing the upper one made the hand advance by one hour, or one time zone; pressing the lower pusher made the hand travel backwards one hour. The second version, ref. 2597 HS had a second blued steel hour hand that was independently adjusted in a similar fashion. This second system, based on a 1959 patent, was manufactured in March 1962. Between 1985 and 1962, Cottier was given around 90 movements (consisting of calibers 12-400, 12-400 AM and 27 AM 400) to modify with the dual time zone. The last ten movements were modified to accommodate the three-hand version in 1962. However, during the 1970s, Patek Philippe’s After Sales Service offered a “third hand parts set” to retailers who still had ref. 2597 in stock which gave them the option to update. Because of this, two or three-hands watches have always been named the ref. 2597. The ref. 2597 remained listed until 1977 and was the inspiration for the Travel Time ref. 5034 and the ladies ref. 4864 which were introduced in 1997 as part of Patek Philippe’s small complications series which included the Annual Calendar ref. 5035.

While working with Patek Philippe, Louis Cottier was able to push his creativity to new heights. This was because Henri Stern, Thierry Stern’s grandfather was at the helm during this time and as an artist at heart, he was willing to explore innovative methods of timekeeping. As much as Stern looked to the future with electronic time keeping and the avant-garde designs of Gilbert Albert, he also embraced the past and encouraged Cottier to conceive and create a magnificent bras-en-l’air (arms in the air) pocket watch depicting a fox and crow based on a fable by Jean de la Fontaine (above). The caliber 17-170 movement was customized by Cottier to incorporate the retrograde system which enables the fox and crow to indicate the hours and minutes along the two numbered sectors. The bras-en-l’air watches were first produced around 1800. Traditionally, this design would depict a human figure, raising and lowering its arms to indicate the hours and minutes on a retrograde scale. The pocket watch was never sold and created as a prototype. It can be seen in all its glory in the Patek Philippe Museum.

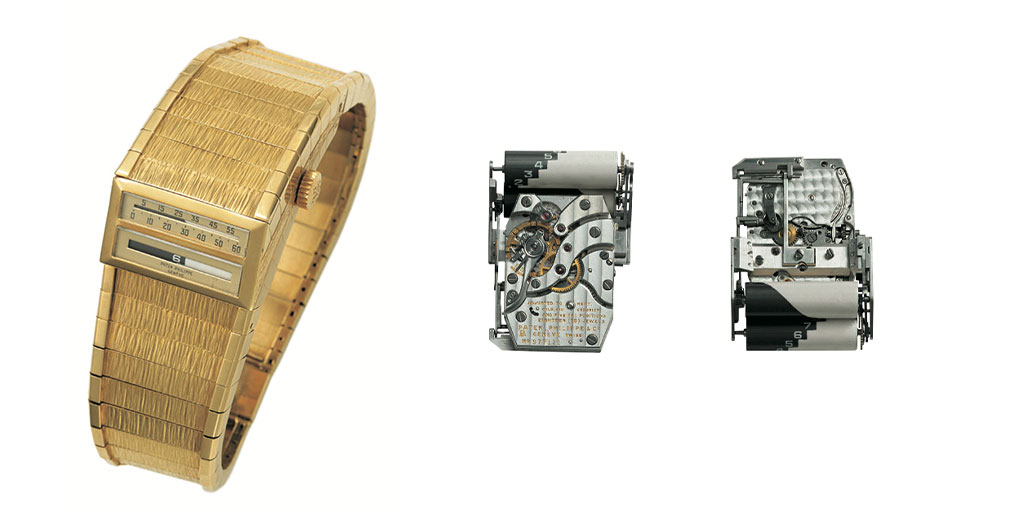

One last prototype that raised the bar of innovation was another Cottier invention. Ref. 3414 is an ingenious wristwatch with a digital time display. Linear displays were very popular during the second half of the 1950s, when they were used for speed indication in car tachometers. Cottier modified a 9”’90 caliber to produce this wristwatch which sadly was never serially produced. The dial is made up of two synthetic cylinders, one for the hours (making one complete rotation every 12 hours), the other for the minutes (making one rotation every 60 minutes). The superimposed cylinders, half white and half black are linked to the motion work. They indicate the hours and minutes in two narrow apertures as they turn.

Today, Patek Philippe still produces watches with Cottier’s inventions and continues to refine them, always aiming to increase ease of use for travelers. In 1999 a patent was filed for the launch of the World Time ref. 5110 in which a single push-piece simultaneously adjusts the city disk, the 24-hour ring and the hour hand.

Different complications have also been added to the World Time such an innovative moon phase to a men’s ref. 5575 and a ladies ref. 7175 for the company’s 175th anniversary in 2014, a chronograph on the ref. 5930 in 2016 and a minute repeater to the ref. 5531 in 2018. The World Time’s cousin the Travel Time has also been enhanced with complications such as the ref. 7234 Calatrava Pilot Travel Time, the ref. 5326 Annual Calendar Travel Time, the ref. 5520 Alarm Travel Time. This year’s launch of the ref. 5224 Travel Time with its refined and legible 24-hour display dial would have no doubt been much admired by Louis Cottier.

April 2023