New York. London. Tokyo. As new long-haul routes connected continents in the 1950s Golden Age of air travel, businessmen and adventurers found themselves crossing multiple time zones with increasing frequency. This era of aviation innovation, expanded international routes, and unprecedented passenger comfort presented an elegant challenge: how does one keep track of time across distant destinations? The watch industry responded with one of the era’s most significant innovations.

It was against this backdrop that Patek Philippe introduced the ref. 2597 Travel Time, a watch that would become one of the manufacture’s most important references despite its limited production. It introduced an ingenious “Heure Sautante” (jumping hour) mechanism that allowed travelers to adjust the hour hand independently – forward or backward – without disturbing the minutes or stopping the watch. This was achieved through two discreet pushers flanking the case. This was practical watchmaking at its finest: elegant, intuitive, and perfectly suited to the jet-setting lifestyle that was just beginning to take shape. The innovation’s significance is underscored by the fact that two examples reside in the Patek Philippe Museum’s permanent collection.

The ref. 2597 represents a fascinating collaboration between Patek Philippe and master watchmaker Louis Cottier, exemplifying the Geneva Cabinotier tradition where independent artisans brought specialized expertise to the great manufactures. Working from his own atelier, Cottier modified Patek Philippe’s supplied movements to create this remarkable complication. Thanks to access to Cottier’s personal archives, this article draws on previously unpublished production records to provide unprecedented detail on the ref. 2597’s creation and specifications. The result was approximately 90 to 110 pieces produced between 1958 and 1962/63 – a watch that married Cottier’s mechanical ingenuity with Patek Philippe’s design excellence.

This article explores the complete story of the ref. 2597, from its technical innovations and Calatrava-inspired case, to the nuances that distinguish different examples: two distinct dial series, the evolution from two-hand to three-hand configurations, the rarity of rose gold pieces, and the notable examples that have captivated collectors at auction. Today, it stands as one of Patek Philippe’s most celebrated vintage models.

Louis Cottier and the Heure Sautante

The relationship between Louis Cottier and Patek Philippe is a prime example of the Geneva Cabinotier tradition. Cabinotiers were skilled artisans – watchmakers, engravers, jewelers, goldsmiths – who worked in their own workshops, perfecting specialized skills while serving various clients. This tradition gradually faded as manufactures became more industrialized and began internalizing specialized skills in the mid-20th century.

Louis Cottier, born in 1894 in Carouge, a city adjacent to Geneva, was the son of watchmaker and inventor Emmanuel Cottier. He attended Geneva’s horological school, exceling as a talented watchmaker. Cottier established his own workshop and by 1931 began offering his inventions to various brands, including Rolex, Vacheron Constantin, Gübelin, and Zenith. Notably, he served as curator of Hans Wilsdorf’s watch collection. The relationship with Patek Philippe started around 1936/37 when Cottier developed the first ref. 605 HU World Time pocket watch. He then went on to create the World Time mechanisms for famous ref. 1415 and ref. 2523, always modifying regular movements supplied by Patek Philippe.

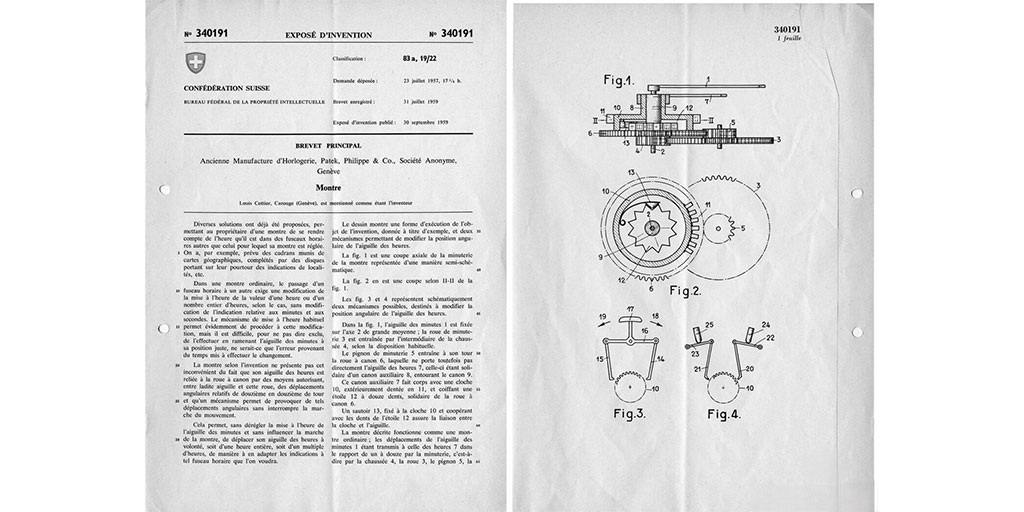

Cottier began working on the Heure Sautante (H.S., “jumping hour”) in 1956/57, a mechanism that allowed wearers to adjust the hour independently without pulling the crown or changing the minutes. This offered a significant advantage when changing time zones, particularly since precise time references for setting personal watches were not as ubiquitous as they are today. This mechanism later evolved to feature a second hour hand that can be set independently, thereby displaying two time zones simultaneously, a proper GMT function. Patek Philippe filed a patent for the jumping hour in 1957 with Louis Cottier named as the inventor and was granted in 1959 under Swiss number 340,191.

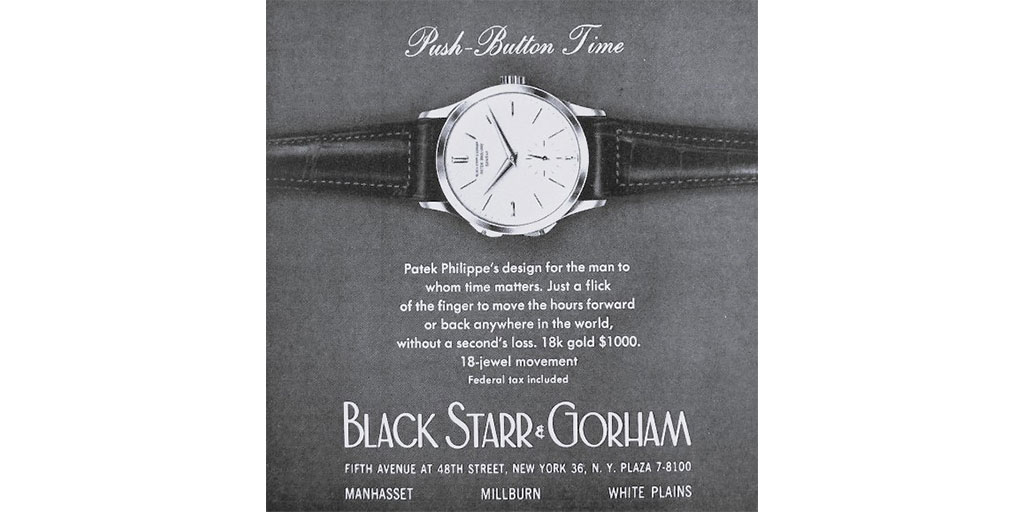

The ref. 2597 was presented to the world for the first time at the 1957 Basel Fair with the first examples sold in 1958 and remained in production until 1962/63. It wasn’t an inexpensive watch at launch: it retailed for $1,000, a hefty price tag when compared to a ref. 1518, which sold for $1,500. It was marketed in the USA as the “Cross Country” or the “Push-Button Time”, highlighting its practical feature in a vast country that spans several time zones, and while sales were certainly slow at the time of launch, it has evolved to become one of Patek Philippe’s most celebrated models today.

The Case

The case of ref. 2597 takes direct inspiration from the ref. 570 Calatrava, a distinguished dress watch introduced in 1938 as a modernized version of the ref. 96. The case measures 35.5mm, which was considered quite large for its era, offering a more substantial wrist presence while retaining the timeless elegance of the Calatrava line.

Like the ref. 570, the case design is notable for its clean, flat bezel combined with vertical case sides, contributing to a purposeful and strong aesthetic. The lugs are a standout feature, with elegantly curved sides that roll gracefully toward the wrist. This creates a clean and refined profile.

The main difference lies in the addition of two pushers at 8 and 10 o’clock. These pushers allow the wearer to move the hour hand forward or backward without using the crown or modifying the minutes. The small pushers are protected on each side by “pusher guards” to prevent unintentional manipulation.

The snap-back case back is typical of watches from this era. The watch is topped with an acrylic crystal, giving the case a total thickness of 9.8mm, maintaining a comfortable and elegant form. The crown is flat and adorned with a Calatrava cross.

The cases were all manufactured by Antoine Gerlach, a longtime partner of Patek Philippe at the time, recognizable by the No. 4 inside the Geneva key stamped inside the case back. Cases were made in either 18K yellow or rose gold, with hallmarks located either on the case profile at 4 o’clock next to the crown or under the lugs. Notably, yellow gold tends to age toward a slightly darker shade, while rose gold ages toward a slightly lighter shade, meaning they can sometimes be confused for one another. An Extract from the Archives is essential to give clarity on the metal.

The Dial and Hands

The dial of ref. 2597 is usually a refined and elegant silver that emphasizes legibility and classic aesthetics. The dials feature all the main characteristics of classic Calatrava watches from the period:

- Engraved enameled PATEK PHILIPPE GENÈVE signature, and 5-second marks of the small seconds at 6 o’clock

- Minute track around the dial with perlage (“pearling”), with slightly larger pearls at the 5-minute marks. Despite the name, pearling has nothing to do with actual pearls; rather, it consists of small holes that reveal the dial metal underneath with concave endings, creating an optical illusion of raised dots.

- Applied faceted gold indexes at 12 (double), 3/9 (single) and 6 (shorter)

- Dauphine hour and minute hands and feuille (“leaf”) second hand

- The word ‘SWISS’ appears at the very bottom of the dial, though versions exist without this indication.

The dials were made by Stern Frères and two series can be distinguished:

- First series (1958-60): Double index at 12; indexes at 3/6/9; raised enamel marks for all other hours

- Second series (1960-63): Double index at 12; indexes at 3/6/9; gold baton markers for all other hours

The second series was probably introduced for two reasons: first, the full gold indexes provided a more luxurious appeal; second, dial manufacturers were starting to transition away from the engraved enamel technique, which was particularly time-consuming and difficult to execute with perfect consistency.

The transition from first to second series happened around 1960, likely from movement number 729,400. The Certificates of Origin or Extract from the Archives do not mention dial series.

At least one example features ‘SWISS MADE’ instead of the usual ‘SWISS’ below the small seconds at 6, likely indicating a later production dial or possibly a service dial.

To assess if a dial has been refinished, one hint is to look at the engraved enamel indications: as originally produced, the enamel was more or less flush with the rest of the dial; if the enamel is too visibly raised above the surface of the dial, it means the top layer, also called zapon, was slightly removed and the dial likely refinished at some point in time.

The Movement

Patek Philippe supplied Louis Cottier with 12-400 movements and later 27-400 movements (which featured a Gyromax balance), which he then modified to create the Heure Sautante, or HS as it was also known.

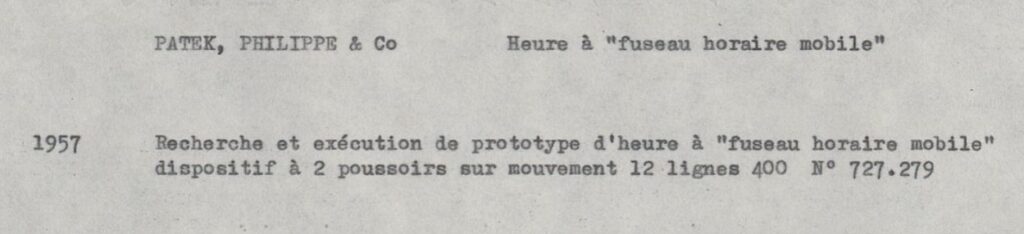

Based on Louis Cottier’s archives, he completed the research and execution of a prototype with “mobile time zone hour with two pushers” in 1957 (heure à “fuseau horaire mobile” dispositive à 2 poussoirs). This was a modified 12-400 movement with movement number 727,279.

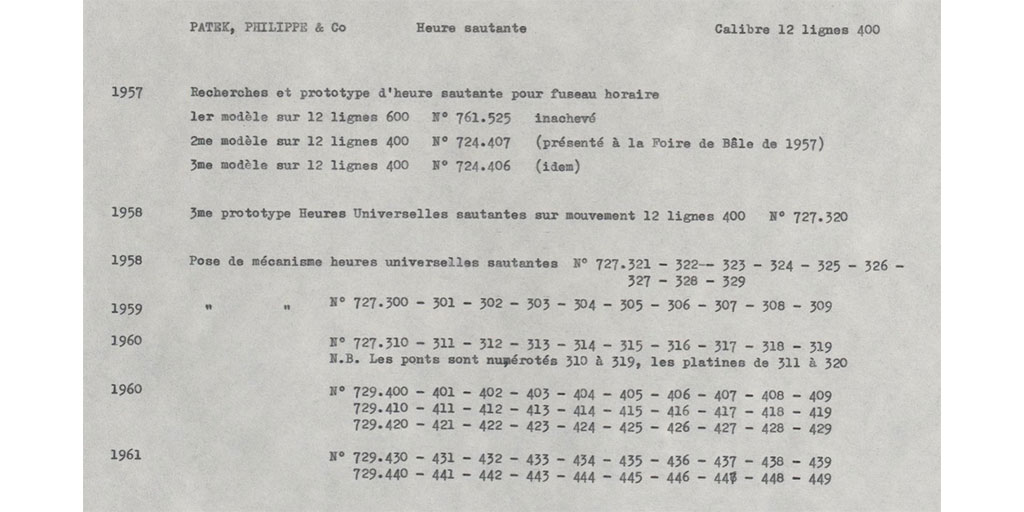

He went on to produce four further prototypes:

- No. 761,525, based on a 12-600 movement, made in 1957 – remained unfinished

- No. 724,407, based on a 12-400 movement, made in 1957 – presented at the 1957 Basel Fair

- No. 724,406, based on a 12-400 movement, made in 1957 – presented at the 1957 Basel Fair

- No. 727,320, based on a 12-400 movement, made in 1958

None of these four prototypes have appeared at public sales and it is not known whether they were offered for sale.

Two-Hand vs. Three-Hand Versions

Two versions of ref. 2597 have been available — either with or without the addition of an extra hour hand to indicate a second time zone. When first presented in Basel in 1957, the model had an hour, a minute and a small seconds hand. Pressing on the buttons at the side of the case would advance/reverse the hour hand in one-hour increments without the need to pull the crown to set the time, thus avoiding changing the minutes. A modified version appeared in 1962 with the addition of a second hour hand made in blued steel. Thus, the main handset in gold would show the time in one time zone, while the time in another time zone can be read with the blued hand. The pushers now advanced the second hour hand. When the second time zone wasn’t needed, the blued hand could be positioned beneath the main hand, rendering it invisible.

However, while two distinct versions exist, it is impossible to establish definitive series classifications as can be done with the dials. Indeed, recognizing that the upgraded version offered clear functional advantages appreciated by clients, Patek Philippe released a ‘third hand part set’ – essentially an upgrade kit – to convert two-hand versions to three-hand configurations. These were available from the 1970s onwards.

Consequently, it is nearly impossible to determine whether a watch originally left the Patek Philippe workshop as a two-hands or three-hands model. Two-hands and three-hands versions appear across the entire serial range of both movement and case numbers and case metals. Even watches with late movement numbers exist with two hands, as proven by this example with movement number 739,729, one of the very last movements made. The only way to confirm with certainty that a watch was originally made with three hands is through a Certificate of Origin that mentions ref. 2597/1, the official designation for the three-hand version. That said, many Certificates of Origins have been lost to time and the Extracts from the Archives do not distinguish between refs. 2597 and 2597/1 versions; it always reads ref. 2597. Lucky owners of ref. 2597/1 with its original Certificate of Origin are the only ones who know with certainty that the watch left Patek Philippe in this configuration.

We have seen nine examples of ref. 2597 at international auctions with a date of manufacture in the early 1960s but sold only in the 1970s and even as late as 1981. These sale dates – recorded on the Extract from the Archives – indicate when the watch left Patek Philippe, which is not necessarily when it reached the end client. So far, all these examples have featured three hands. It is thus likely that Patek Philippe internally upgraded the watches they still had in stock to the improved version to facilitate sales.

Production Numbers by Series and Metal

A total of approximately 90 to 110 ref. 2597 watches were produced.

A first batch of production results from Louis Cottier’s personal archives where 79 pieces — modified 12-400 movements — are recorded, bearing movement numbers 727,300 to 727,329 and then 729,400 to 729,449. Two notable points: first, the initial batch produced in 1958 ranged from 727,321 to 727,329 (rather than starting at 727,300 as might be logically expected); second, No. 727,320 was a prototype and has been excluded from production totals. The details per year can be seen in the document below. As one of the prototypes was sold (No. 727,279 from 1957), one can wonder if the three other complete prototypes were sold as well.

A second batch of watches bearing movement numbers in the 739,7xx range has sold publicly, though these are not recorded in Cottier’s archives. Based on the serial numbers, this last batch was likely made in between 15 and 25 pieces. Watches from this last batch are likely all modified 27-400 movements.

Regarding dial series, watches with movement numbers up to 727,329 were generally made with first series dials – representing about 30 pieces and thus the rarest – while subsequent models featured second series dials, totaling approximately 80 pieces. As always with watches made in this period, this is more a general guideline than an absolute rule and exceptions do exist.

Regarding metals, the majority of pieces were made in 18K yellow gold. Rare, 18K rose gold watches are in a tight serial batch, suggesting they were produced at the same time with consecutive numbers. Known example all have a case number between 309,779 and 309,790. This suggests that approximately 12 to 15 rose gold examples were produced, meaning 75 to 95 were made in yellow gold. Notably, with only one exception known, all rose gold examples have been made with a first series dial.

Due to the fact that two hand versions could have been upgraded at a later stage to three hand versions, it is impossible to reliably estimate how many have been made in which execution. So far from auction results, about two-thirds of the unique examples sold had 2 hands, while one-third had three hands.

Notable Examples

Double-signed dials

As was common at the time, Patek Philippe produced double signed dials bearing both the Patek Philippe and the retailer’s names. The following examples have appeared at auction:

- Gobbi Milano, Italy – 1 first series dial known, last sale at Phillips, New York, 2018

- Gübelin, Switzerland – 1 first series & 3 second series, last sale at Phillips, Geneva, 2016

- Hölscher, Germany – 1 second series known, last sale at Antiquorum, Geneva, 1999

- Tiffany & Co., USA – 2 second series known, last sale at Phillips, Geneva, 2017

An example bearing the Black Starr & Gorham (USA) retailer signature likely exists, as it appeared in one of their advertisements, though it has not yet surfaced publicly (see the ad image above).

The placement of the retailer signature has varied from above Patek Philippe at 12, under Patek Philippe at 12, above the small seconds at 6 and within the small seconds at 6 (see above).

These pieces often sell slightly above their non-double-signed counterparts, however, due to the infrequent sales, it is hard to draw conclusive comparisons.

First series luminous dial

One watch has appeared on the market featuring a first series dial with luminous dauphine hands and luminous hour markers, made in rose gold with three hands. It was sold at Christie’s Geneva in 2013 for $505,000. Remarkably, the watch was made in 1963 but not sold until January 8, 1981 – seventeen years later. It is quite likely that it was made at a client’s request, with luminous markers added to an existing first series dials and the three-hand upgrade performed by Patek Philippe before being delivered.

Breguet numerals dial

Two watches are known to exist with full Breguet numerals (except at 6 where the small seconds is located):

- No. 727,310 with silver dial and two hands – Christie’s, Geneva, 2010, $219,000

- No. 729,444 with gilt dial and three hands – Christie’s, Geneva, 2001, $171,000

This second watch is also the only one known with a gilt dial.

Second series blue dial

A single watch appeared on the market with a blue dial. What is notable is that it bears movement number 727,279 which is prior to the regular production range. The case number 309,370 is also the first known and prior to the regular production range. The watch last sold at Sotheby’s, New York in 2023 for $101,600.

The Louis Cottier archives tell us that this is the very movement that was used to make the very first prototype in 1957. Patek Philippe issued an Extract from the Archives for this watch confirming it was made in 1957 and sold on August 23, 1961 so the prototype was certainly made into a sellable piece. Since it features a second series dial, which was only produced from 1960 onward while the watch itself was made three years earlier, this raises the question of whether the watch originally came with this blue dial or if it was added later. The Certificates of Origin do not mention the type of dials used.

Collectability

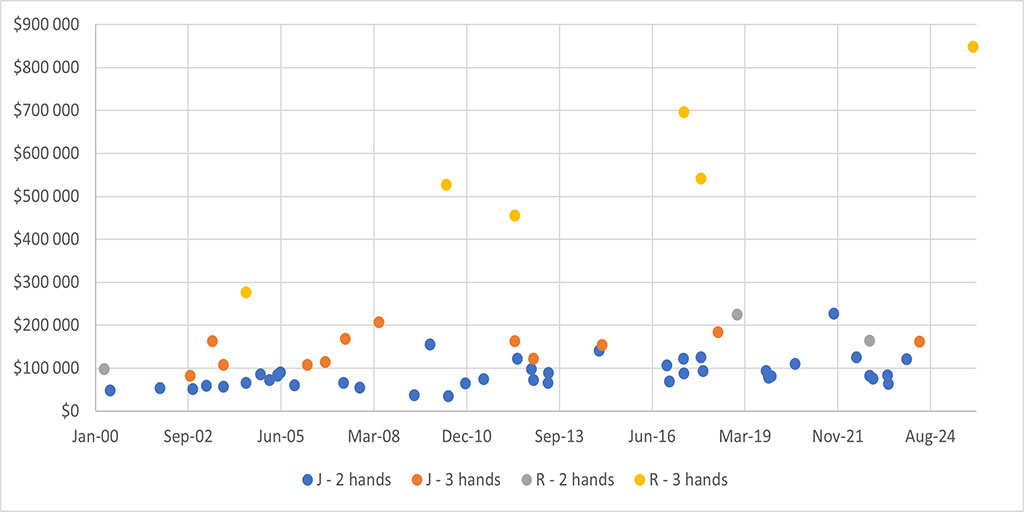

Beyond these exceptional examples, the broader auction market for the ref. 2597 reveals clear patterns in collector preferences and pricing. Since 2000 ref. 2597 has appeared 78 times across Antiquorum, Bonhams, Christie’s, Dr. Crott, Monaco Legend Group, Phillips and Sotheby’s, with 44 unique examples after having removed duplicate sales. The results below are converted to USD at the exchange rate on the day of each sale.

The most desirable configurations are in order:

- Rose gold with three hands – 5 occurrences, average price: $499,000

- Rose gold with two hands – 3 occurrences, average price: $162,000

- Yellow gold with three hands – 14 occurrences, average price: $145,000

- Yellow gold with two hands – 50 occurrences, average price: $86,000

Several interesting patterns emerge:

- Rose gold is the rarest metal and commands a significant premium over yellow gold

- Three hand configurations command a significant premium over the two hand versions

To prove how much these two factors play into the value of a ref. 2597, the most recent watch to sell at an auction in Hong Kong over the weekend (November 2025), a fresh-to-the-market, pink gold double-signed ref. 2597/1R, sold for a staggering HK$6,604,000.

Also of note is what the market does not yet seem to value: to date, there have been no significant price differences between first and second series dials, despite first series dials representing less than one-third of total production. First series dials also offer the additional craftsmanship and vintage charm of enameled hour markers. I would not be surprised if collectors start to distinguish more between these two series going forward.

A word of caution is warranted regarding versions with three hands. As they command higher prices, we have seen at least two examples that sold publicly, which were first offered with two hands and subsequently modified to a three-hand version in the late 1990s/early 2000s, in both instances achieving higher prices after the transformation: No. 729,309 (two hands in 2001 and three hands in 2002) and No. 729,407 (two hands in 1995 and three hands in 2014).

It is important to keep in mind that not all watches with three hands left the factory in this configuration in the first place and it is only being officially documented on watches with a Certificate of Origin mentioning ref. 2597/1. While undeniably an important feature, it is not possible to know how many left the factory as three-hand models and how many were subsequently upgraded and if upgrades are still possible nowadays by watchmakers who happen to have three-hand conversion kits.

Conclusion

For collectors considering the ref. 2597, the choice between two-hand and three-hand configurations comes down to personal preference. Purists may favor the original two-hand versions, while others prefer the superior functionality of the three-hand configuration. Neither is inherently better; what matters is understanding your watch and ensuring proper documentation. The distinction between first and second series dials also deserves greater collector attention, particularly the craftsmanship of first series raised enamel markers. As the market matures, these nuances may be more clearly reflected in valuations.

The ref. 2597’s significance extends far beyond its limited production. Louis Cottier’s ingenious jumping hour mechanism laid the groundwork for Patek Philippe’s entire Travel Time lineage – living on in successors like the refs. 5034, 4864, and today’s refs. 5326 and 5224. From its origins as a slow seller to today commanding six-figure sums and residing in the manufacture’s own museum, the ref. 2597 stands as testament to how functional innovation, when executed with elegance, can transcend its era. It remains a milestone in the evolution of the traveler’s watch – a perfect marriage of mid-century optimism, mechanical ingenuity, and timeless design.

Louis Cottier’s personal archives are kept in the Musée des Arts et d’Histoire (MAH) in Geneva, Switzerland and have recently been digitalized by The Watch Library Foundation.

Edouard Henn has been passionate about horology since his teenage years. He began his professional journey in the watch industry in Switzerland before transitioning to luxury retail across Europe and the Middle East. With a business education background, Edouard brings both product and collector’s perspective to his writing. Now based between Geneva and Paris, he enjoys sharing horological knowledge and connecting with fellow enthusiasts in the watch community.